Review: One Battle After Another (2025)

For all of his accomplishments, Paul Thomas Anderson has never demonstrated a mastery of genre. Boogie Nights gestures at the crime picture via the films of Martin Scorsese. Punch-Drunk Love plays with romantic comedy conventions. Inherent Vice is a stoner comedy at points, as well as a neo-noir, and Licorice Pizza is a high school film, in a way. But none of these movies are interested in delivering pure genre entertainment, never giving us the stylistic and narrative hits that we crave in genre pictures, even if they’re alternatingly fascinating and exceptional in their own ways. But One Battle After Another is a great action thriller in addition to being a great movie. Not that it’s only an action thriller. It’s inspired by Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland, after all, and so has the distinctive blend of paranoia, political esoterica, and American goofery that you’d expect from a Pynchon work. But it excels on the generic level, with thrilling action scenes, inventive chases, and a genuinely propulsive thrust for a film that runs 162 minutes.

This picture really moves—narratively, emotionally, aurally—right from the first frame. In the opening moments, Anderson drops us into a raid on an immigrant detention centre on the Mexico border. We watch members of the French 75, an American left-wing revolutionary group, take the guards hostage, blow up equipment, and truck out dozens of incarcerated migrants. We meet revolutionaries Perfidia Beverly Hills (Teona Taylor) and Ghetto Pat Calhoun (Leonardo DiCaprio), who thrive on their shared love of revolution, and eventually have a child together. But while Pat feels that they must adjust their lifestyle for the sake of their child, Perfidia believes that the revolution stops for no one, and continues her fight for social upheaval, familial responsibilities be damned. She disappears into the heat of battle, while Pat shifts gears into dad mode, and goes into hiding, adopting the new identity of Bob Ferguson and raises their daughter, Charlene, now called Willa (Chase Infiniti), on his own away from the revolutionary world.

The film’s opening third follows the French 75’s revolutionary activities, as Perfidia and Pat/Bob forward the revolution until Charlene/Willa’s appearance forces a reckoning. Taylor’s Perfidia is fire and brimstone, a mad rush of revolutionary energy and sexual and emotional abandon that lights up the screen. Anderson, perhaps channeling his own love for his wife, Maya Rudolph, and women of her type, transforms Perfidia into a dynamo of black female agency, and Taylor completely relishes the sheer energy of the character in these early moments. We get her holding up Sean Penn’s Steven J. Lockjaw at gunpoint during the early camp raid (Lockjaw soon becomes the film’s other central figure), blowing up political offices, and robbing banks with her compatriots. In these moments, the camera is in awe of Perfidia, shooting her from low angles like she’s a towering, mythic figure, the editing moving propulsively forward from one revolutionary action to another, Johnny Greenwood’s score embodying the slippery electricity of revolution.

Perfidia looms large over the film, even when she disappears, as her antagonistic relationship with Penn’s Lockjaw fuels the film’s narrative turns. In the second act, we catch up with Pat, now Bob, and the teenage Charlene, now Willa, as well as an older and more bitter Lockjaw. Perfidia is gone, but her actions continue to reverberate, cashing a cheque that’s come due for Bob and the other former revolutionaries of the French 75.

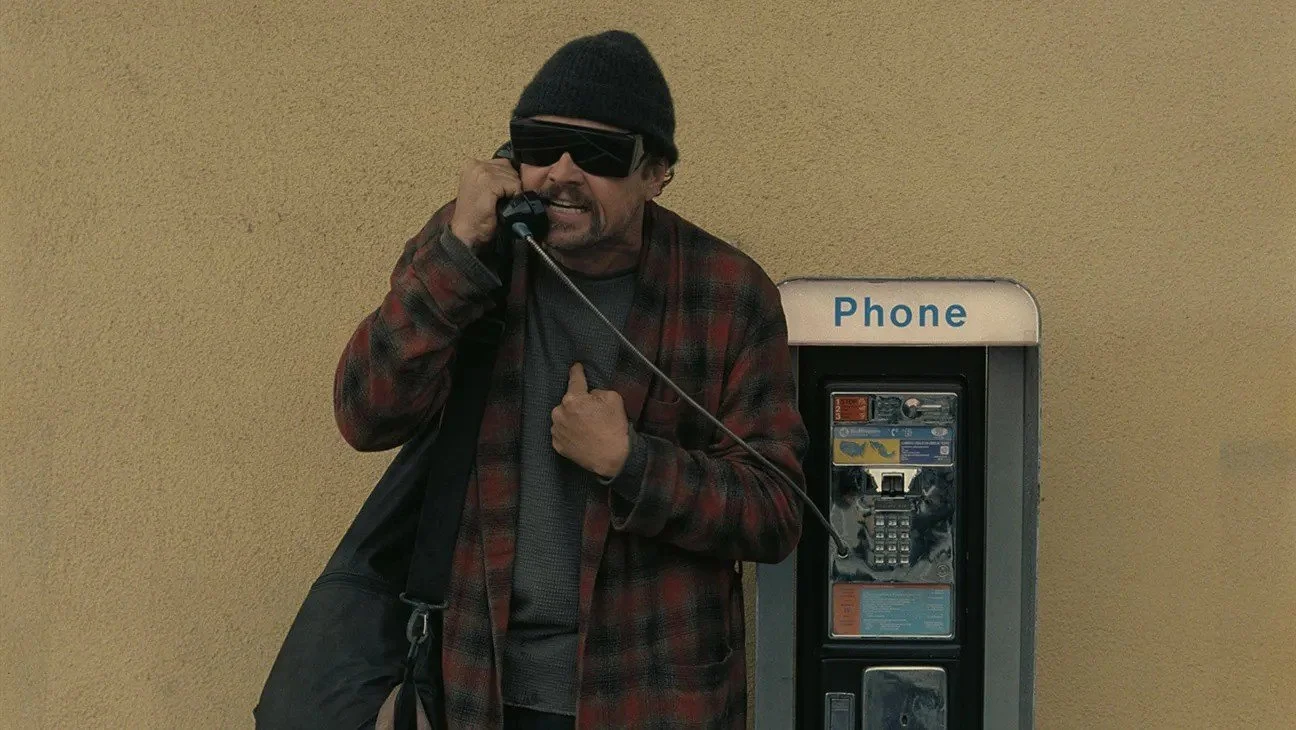

From then on, One Battle After Another becomes something of a chase film. Lockjaw is trying to find Willa. After Bob and Willa flee, they get separated and Bob is also trying to find Willa. Willa is trying to escape it all, not really sure of what she’s got herself into since her father has kept so many of the secrets of his past from her. The journey takes us from the rural cabin where Bob and Willa live to an urban centre under siege by immigration forces to a remote nunnery and through the hills of northern California. Key to the film’s impact as an action film is its exceptional set pieces, particularly two extended sequences, one midway through and another near the end of the film.

The first sequence is practically an urban warfare scene where Bob, aided by his friend and Willa’s karate sensei, Sergio (Benecio del Toro), maneuvers through a downtown core of a sanctuary city where protestors are set to riot against Lockjaw’s law enforcement squads who have taken over every square inch. Bob needs to get out alive and Sergio, with his underground network for moving illegal migrants, is the man to do it, but it won’t be easy as around every corner lie heavily-armed soldiers ready to round up anyone and everyone.

It’s easily Anderson’s largest scale sequence to date, with hundreds of extras and dozens of locations throughout the downtown core of the city. Bob and Sergio weave in and out of apartments and corner stores, navigating via back alleys and rooftops. Anderson’s camera, ever so elegant when trucking in parallel to the action, moves along with Bob and Sergio as the city descends into chaos, with firebombs and rubber bullets flying. It’s riveting, but especially brilliant as it weaves in slapstick humour and the endlessly amusing sight of Bob, wearing a Big Lebowski-esque bathrobe for the second half of the film, scurrying around like a stoner caught in the last place he ever hoped to be (which is pretty much what he is). It all leads to a car getaway where Sergio gets Bob to safety while the two enjoy “a few small beers,” a line delivered to perfection by del Toro, sporting one of the best smirks on screen in recent memory.

If this downtown siege sequence perfectly demonstrates Anderson’s abilities to both broaden the scale and simultaneously weave-in distinct tones, all within a single riveting action sequence, the climactic car chase shows Anderson’s abilities to tighten the screws and create unbearable tension with his camera and the rhythm of his music and editing. In the climax, Willa flees in a commandeered car pursued by a villain who is in turn pursued by Bob in a janky street racer. The cars race up and down the rolling hills of northern California, and Anderson ingeniously mounts the camera on the front of the vehicles so we get a rolling phantom carriage ride up and down, up and down, the car in front disappearing and reappearing with each new hill on the highway. It creates a hypnotic rhythm, amplified by Greenwood’s jangling score, with the stakes in the narrative at their most dire. And then, just when we don’t think Anderson can surprise us anymore, we realize he’s used the up and down rhythm to lull us to sleep, just like one of the characters, completely unaware that the rolling hills hide things until they’re right in your face and it’s too late to swerve away from the blind summit at the top. It’s brilliant and a rush, Anderson using the camera and editing to subconsciously teach us what to expect in the scene’s resolution so that when it finally comes, it’s completely unexpected but feels absolutely right for the scene and the film.

Anderson has made some great films, but One Battle After Another represents significant growth in his mastery of style and filmmaking technique. Of course, others are more drawn to the film’s timely political messaging, since its tale of revolutionaries set against an increasingly authoritarian, anti-immigrant state seems ripped from the headlines. This timeliness will likely do the film well come awards season, but as with most great works of art, the film is more complicated than the commentators will have you think. For one, while the film’s sympathies lie undeniably with the French 75 characters, it is not uncritical of these revolutionaries, specifically Perfidia Beverly Hills, who personifies the idea of outward revolutionary political action being an expression of deeply selfish, chaotic internal fixations. Perfidia and Lockjaw become the film’s binary systems, where the political and the personal mesh in a perfectly twisted psychosexual cocktail. Considering Lockjaw, I’ve gone long, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t address what a marvelous character he is, and what a great performance Sean Penn gives in the role.

I never expected to love Sean Penn in a movie, but here we are, with Paul Thomas Anderson using Penn so effectively as a comic villain who is deeply pathetic and deeply terrifying. Walking with a perfectly stiff military stride, like a steel pole is lodged so firmly up his ass that it controls his entire gait, and speaking with a brusque manner that holds his jaw in such a way that you interpret his name as description, not just nomenclature, Lockjaw is a brilliant physical creation.

We first meet him in the opening scene as the commander in charge of the detention centre, but we don’t leave him there, instead learning more and more about his childish military ambitions and deeply confused mixture of racial and sexual preferences. He aspires to be a member of the Christmas Adventures Club, a white supremacist Deep State group that is perhaps the film’s most distinctly Pynchonian creation, but he also “loves black girls,” as he effusively and vulgarly spits in Bob’s face during an early innocuous encounter. He wants to be a good soldier for a greater cause but uses his unit to act out personal fantasies of power and domination. He’s a goofball in moments but remarkably unbreakable in later moments, like a Terminator in how he just doesn’t give up, no matter what physically happens to him. Penn’s go-for-broke, self-serious acting style meshes perfectly with Lockjaw’s self-serious creation, bringing the man’s contradictions and insecurities to the fore. It makes me appreciate the level of commitment that only a doofus actor who takes themselves too seriously can give to a role. It’s impressive.

There’s so much to love about One Battle After Another, but that it made me genuinely appreciate Sean Penn as an actor and reflect positively on his approach to the art of acting is perhaps the most surprising. Anderson, 10 films into his remarkable run as one of the leading American filmmakers, continues to show off new tricks.

9 out of 10

One Battle After Another (2025, USA)

Directed by Paul Thomas Anderson; written by Paul Thomas Anderson, based on Vineland by Thomas Pynchon; starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Sean Penn, Benicio del Toro, Regina Hall, Teyana Taylor, Chase Infiniti.

This mockumentary starring Matt Johnson and Jay McCarrol is a complex metafiction farce and a loving portrait of friendship and Toronto.