Hot Docs 2022: A Symphony for a Common Man

Depending on your trust in the American state apparatus, the revelations of José Joffily’s A Symphony for a Common Man will seem shocking or sadly all too believable. The film traces the career of Brazilian diplomat José Bustani, who was appointed the first general director of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) in the late 1990s, only to be forced out of his position due to American pressure in the lead-up to the war in Iraq. It’s a film that shows how superpowers override the good intentions of international organizations and how easily media narratives are built out of disinformation campaigns and disseminated due to political pressure.

A Symphony for a Common Man is an assembly of archival footage and modern-day interviews with Bustani as well as interesting figures in the world of global affairs and international politics, including former WMD inspector Scott Ritter and former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (known as Lula). The film tells the story of Bustani’s career as a diplomat and his good faith attempts to deescalate military tensions and work towards the decommissioning of chemical weapons around the globe.

The central focus of the film is Bustani’s attempts to get Iraq to join the OPCW prior to 9/11 and the fallout of his refusal to bow to American political pressure. We trace this history by cutting back and forth between talking head interviews, archival footage, and the occasional voiceover interjections of director José Joffily. We learn how Bustani, as well as other WMD inspectors at the time, including Scott Ritter, understood that Iraq’s arsenal of chemical weapons from the late 1980s had expired and that they had not been able to construct any new chemical weapons due to sanctions and supervision in the wake of the Gulf War. For instance, Ritter explains that chemical weapons have a shelf-life of around five years, so by 1999, let alone 2003, the Iraqi stockpile would’ve been rendered useless.

And yet, after 9/11, the Americans claimed Iraq had WMD and were developing more as a pretext for an American invasion of Iraq. Bustani knew this was incorrect, so he attempted to get Iraq to join the OPCW, thus precluding the justification for the war. Alas, Bustani was not successful and the Americans pressured other nations to oust Bustani as the general director of OPCW, replacing him with a more pliable figurehead.

As America’s invasion of Iraq is one of the foundational events of the past two decades, there’s no mystery about the fate of Bustani’s role in the OPCW or his attempts to combat the misinformation narratives about WMD. And yet, it’s still fascinating to listen to Bustani discuss this period with two decades of added insight. He reflects on how things have or have not changed and still speaks highly of the integrity of individual inspectors and the overall mission of organizations like the OPCW.

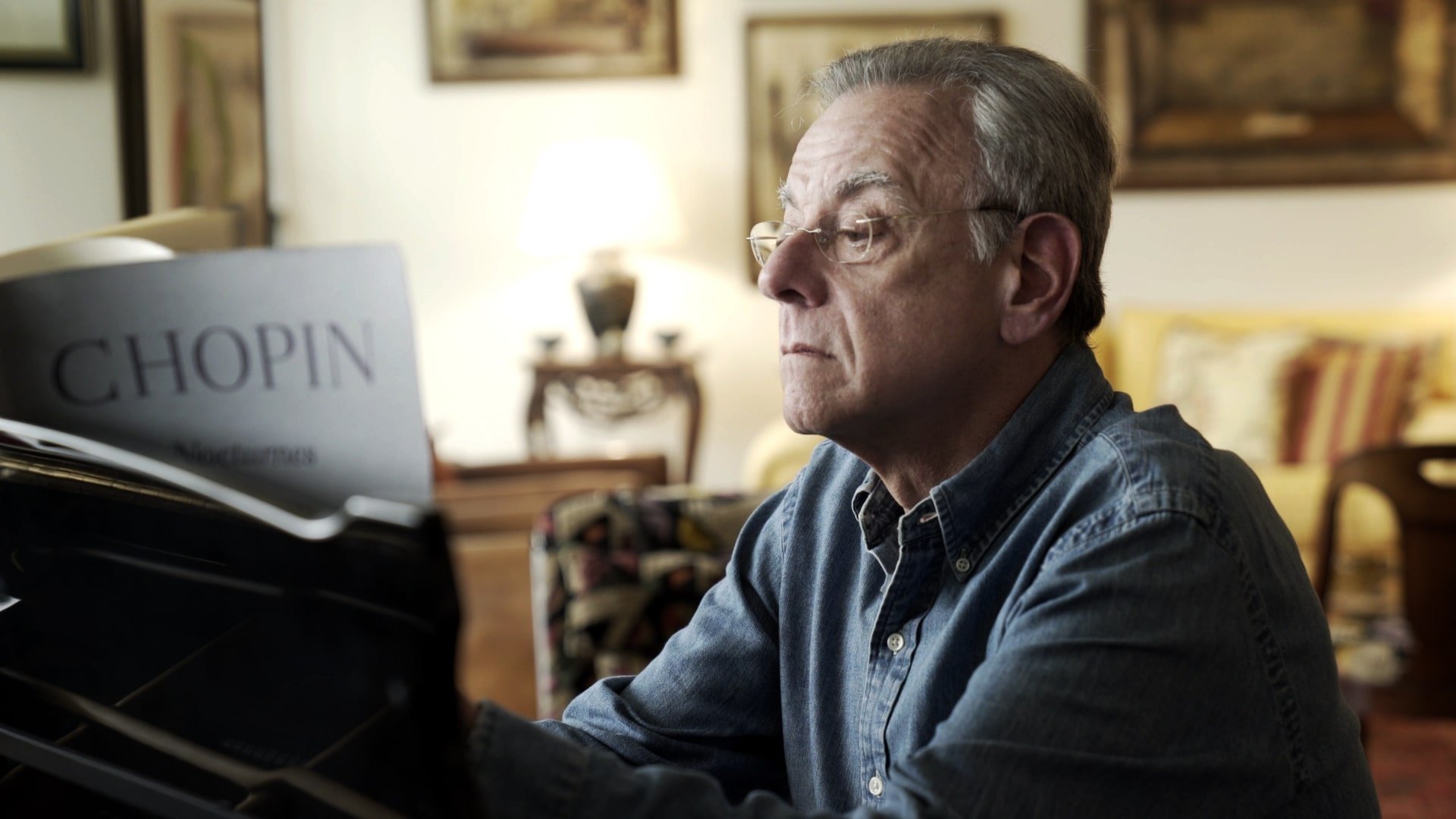

We learn much about Bustani as an individual, both personally and professionally. We learn about his love of music and his left-leaning politics and his pride in his work. The film is framed around Bustani preparing for a piano recital alongside an accomplished orchestra in Brazil. In the earliest moments of the film, Bustani complains about the quality of a prearranged grand piano, refusing to play it due to its tinny sound. Evidently, the man is passionate about piano and quite skilled at it. When we finally see him play, it’s a marvel that his aged hands can move so quickly and softly along the piano keys. Director José Joffily uses a classical score for the film to bring Bustani’s love of music into the other avenues of his life, underscoring how his passion for music parallels his passion for politics.

We also see how these political passions haven’t left him, even as he’s moved into retirement. At one point, he’s prepared to video call into the United Nations Security Council meeting to discuss the 2018 alleged chemical weapons attacks in Douma, Syria, but the diplomat from the United Kingdom forces a vote on allowing Bustani’s appearance. The council predictably votes against his appearance, presumably pressured by the US and the UK. Bustani stands up from behind his laptop, dejected, a half-smile trying to disguise his anger at being once again rebuffed from telling the truth on the world stage.

A Symphony for a Common Man persuasively connects the world in the wake of 9/11 to the world of today, showing how disinformation and backdoor political pressure were de rigueur long before Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump popularized the term “fake news” and before Western governments created panels to combat so-called political disinformation. It also questions official narratives about the use of WMD, first in relitigating how claims of WMD in Iraq were fake, then moving on to the alleged attacks in Syria, which most inspectors privately agree were likely not the work of the Syrian government—contrary to official statements. The film never brings up the Russian war in Ukraine, but again, it encourages us to be skeptical of statements made in order to push forward national interests in the midst of conflict.

Bustani’s story helps us see how there is always more to narratives than is convenient for superpowers or bandied about on mainstream news networks. The film is a document of a man important to a specific time and place, but it speaks to a timeless need for transparency and integrity in international relations that has added urgency during the crises of our present day.

7 out of 10

A Symphony for a Common Man (2022, Brazil)

Directed by José Joffily.

This mockumentary starring Matt Johnson and Jay McCarrol is a complex metafiction farce and a loving portrait of friendship and Toronto.