James Cameron: True Lies (1994)

What if James Bond had a wife and kids? What if they didn’t know he was a secret agent? Such is the high concept premise of 1994’s action-comedy True Lies, one of the true outliers in James Cameron’s oeuvre for a number of reasons.

The first is its genre. While Cameron is a hopeful director, he isn’t known for his sense of humour. Sure, there are comic moments in the Terminator films, especially the second, and Cameron loves a one-liner that brings a grin to your face, but most of his films are neither laugh-out-loud comedies nor even action films with constant jokey banter. True Lies in contrast is a straight up action-comedy. It even works as a screwball comedy, playing off the personalities of its main characters, and has elements of satire, in that it mocks and points out the absurdities of the spy-action genre by pushing them to the extreme. The premise is fundamentally goofy; the casting of Cameron’s Terminator himself, Arnold Schwarzenegger, with his massive physical stature and thick Austrian accent, in the role of a devoted family man and an American superspy is sure to raise eyebrows, if not draw outright mockery.

The second reason is that, barring the false-start of Piranha II, True Lies remains the James Cameron film that is the most mixed in its critical reception. With a respectable 70% on Rotten Tomatoes, it still remains the lowest score of any of his post-Piranha II films. Even upon its release in 1994, it was accused of sexism and misogyny, and was labelled Islamophobic for its portrayal of the Islamic terror cell, the villainous Crimson Jihad, nearly a decade before 9/11. How then does it play today considering changing social mores? It is hard to simply wave these elements away, since they’re so central to the film’s plot, but they also might perhaps not be entirely what they seem to be on the surface.

True Lies’ strange status, as a genre and critical outlier in Cameron’s filmography, makes it a transitional film, and while we marked the end of Cameron’s first phase with Terminator 2: Judgement Day, I would argue that True Lies straddles the line between that first phase of Cameron’s career while hinting at what was to come in terms of big budgets and romantic blockbusters. That alone makes it worthy of examination. And yet, I contend that while it’s a step down from his remarkable four-film run from The Terminator to its sequel, True Lies remains an eminently watchable and entertainingly wild action film on many levels. It also contains many of the hallmarks of what makes James Cameron so successful as a director. It’s worth unpacking True Lies a bit, for the strange, but not-so-little, film that it is.

After the phenomenal success of Terminator 2: Judgement Day, the pressure was on Cameron and whatever film was to be his follow up to one of the biggest hits of all time. In the wake of T2’s success, Cameron spent time restructuring his production company, Lightstorm Entertainment (so-named for the lightning that marks the arrival of the time travellers in his Terminator films) and creating his own visual effects company, Digital Domain. Securing the right to make films his way, without studio interference, was paramount. He arranged a then unprecedented $500 million multipicture distribution deal with Fox, which granted him ownership of his material and the right to go to production without approval up to $70 million. While that deal wouldn’t hold, it was clear that Cameron was the toast of Hollywood. Everyone was curious what his next film would be.

And while the next film he directed ended up being True Lies, one thing that seemed certain to Cameron from the start was that he would try something different. He didn’t want to be pigeonholed as a “sci fi-action guy,” and initially he planned to direct a smaller drama about multiple-personality disorder, called “The Crowded Room.” But when that project collapsed, he felt the pressure to make the first film in his Fox distribution deal a crowd-pleaser. He would reunite with his Terminator star, Arnold Schwarzenegger, who brought Cameron a small French comedy called La Totale!, a farce about a French spy whose family is unaware of his real job. While La Totale! isn’t an action film, Cameron saw the potential in the premise for what he would end up calling his “domestic epic.”

True Lies is the closest Cameron gets to making a full-on James Bond film, and the movie contains many of the hallmarks of the British super spy series: exotic locales, black tie affairs, femme fatales, and life and death stakes. But the premise of the film, in which American secret agent Harry Tasker (Schwarzenegger) must hide his covert actions from his family who believes him to have a boring office job, offers what Cameron saw as a corrective to the Bond fantasy. As recounted in Rebecca Keegan’s The Futurist, Cameron explains: “Bond himself is a pathetic eternal bachelor who will never know the truth of what it is to be a man, to be a husband and father, which is why that fantasy works, especially for married men. Because Bond has nobody to answer to.” While James Bond famously pledged loyalty to the queen, ultimately Harry Taskher has his own majesty that demands his loyalty: his wife.

Central to the premise of the film is the eventual entanglement of Harry’s wife, Helen, in the film’s spy plot. Just as the healing of the marriage between Bud and Lindsey in The Abyss resolves the plot of that film, True Lies makes the revelations of Harry’s real job, and the synthesis of the domestic and globetrotting double-lives that Harry lives, essential to the very structure of the film. Comedically, this reintegration of this relationship is achieved in classic screwball-style, through misunderstandings, false identities, and a back and forth banter. Narratively, the balance between the two leads is what resolves the conflict on the interpersonal level.

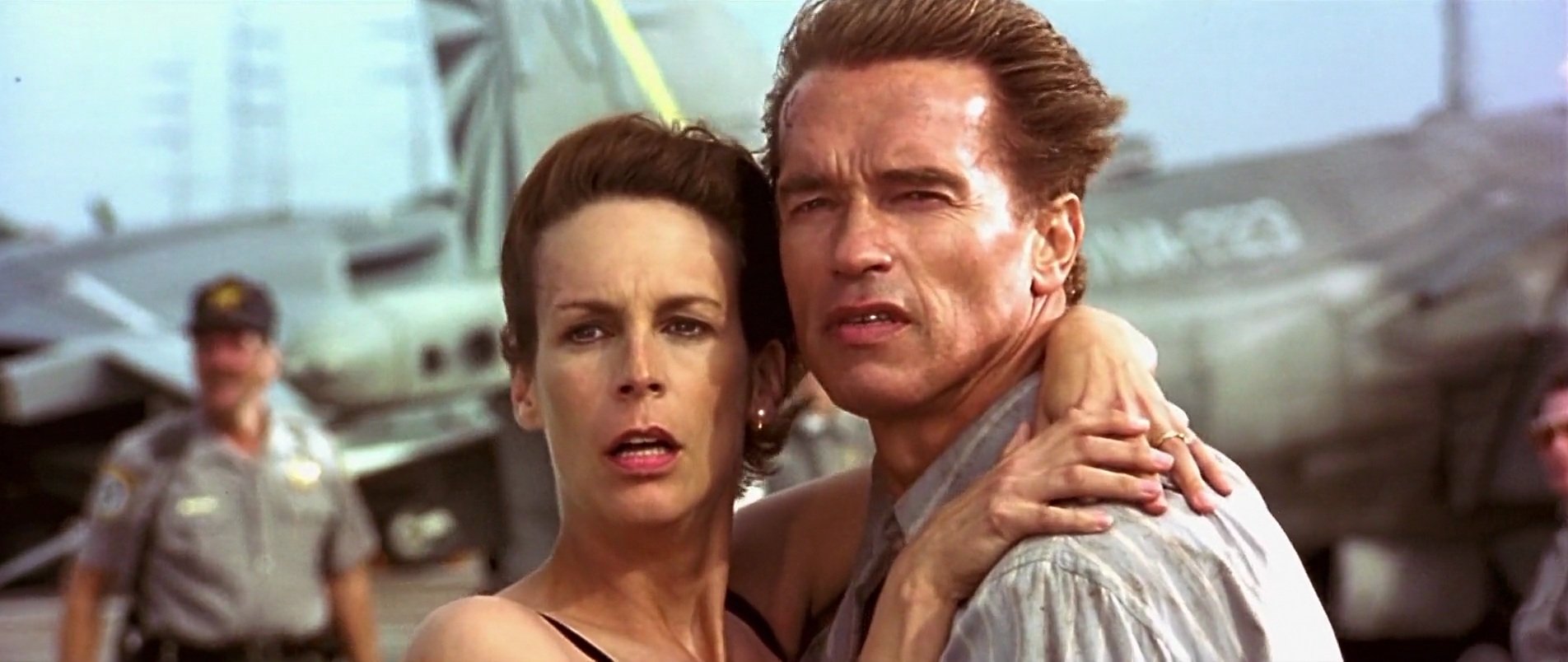

In order to do that Cameron needed to cast a leading woman who could pull off the job of being both believable as a dowdy wife but also as a sexy super spy. She had to be believable in the comedic, domestic, and action scenes and to be credibly sexy. That’s a big bill. The woman who Cameron decided upon was the Scream Queen herself: Jamie Lee Curtis. While Schwarzenegger was initially opposed to the casting (apparently his friendship with Jamie Lee’s father, Tony Curtis, meant he had trouble with the romantic scenes, seeing her as his friend’s daughter), the opinion of Cameron himself carried the day and he even got Schwarzenegger to share his above the title credit with Curtis!

When True Lies debuted in 1994, it had been five years since the last James Bond film, Licence to Kill. GoldenEye would come out the next summer, but audiences were clearly ready for the kind of globetrotting action associated with 007. The opening of True Lies promises the kind of spy action audiences associated with Bond. The film opens with Brad Fiedel’s propulsive score over the black and white titles announcing “A Lightstorm Entertainment Production of… A James Cameron film,” before we get the two stars and the film’s title. The film then takes us to a snow covered villa in the Alps—“Lake Chapeau, Switzerland '' as the on screen title informs us (there is no such place, as French speakers can likely guess based on that name). A glamourous black tie party is being held by a Middle Eastern billionaire for the world’s rich and powerful. In case the pre-title declaration of the film being thoroughly Cameron’s isn’t clear, the scene cuts to an underwater sequence! A diver cuts through the underwater barrier and emerges from the frozen lake, removing his frogman suit to reveal Schwarzenegger in a full black tuxedo. The scene recalls the opening scene of Connery in Thunderball (another film about retrieving nuclear warheads from a global terrorist threat).

The opening sequence at the Swiss villa gives the viewer everything one could hope for from a spy film opening. Harry is aided by his fellow American intelligence operatives, Tom Arnold’s Gib and Grant Heslov’s Faisil, who communicate with him via a sub-vocal earpiece from a van in the nearby mountains. Harry is completely the dashing spy, showing how charming Schwarzenegger was at his peak as an actor, never just a muscle-bound lunk. Harry speaks to the staff and guests fluently in multiple languages, climbs up the outside of the building and hacks the computer of the host, and dances a tango with an intriguing art dealer (Tia Carrere), before walking out the front doors and detonating a bomb he planted earlier as a distraction. The film then gives us a full-on James Bond chase, showcasing Cameron’s skills as an action director once again. Harry is pursued by dogs and men on skis and snowmobiles, escaping down the side of the mountains until his fellow operatives can extract him.

The opening of True Lies promises very successful action with jokes of varying success (I’ve never been a big fan of Tom Arnold, who in my opinion is the film’s weakest link). But after the explosive opening, the film shifts its attention to the establishment of the domestic plot. Harry returns to his home in suburban Virginia outside Washington, D.C. to snuggle into bed with his wife, Helen, who believes Harry was at a sales conference in Geneva. The film shows us the tensions that exist in the domestic situation of Harry and Helen. While Harry is in fact quite fond of his family and is, in his own mind, a loving husband and father, his dedication to his job with the fictional intelligence agency, Omega Sector (“The Last Line of Defense” reads their seal) means he’s often home late. He often misses important family events and is barely aware of the changes in the life of his young teenage daughter, Dana (a pre-Buffy Eliza Dushku), who is stealing cash and riding on motorcycles with boys. He fails to realize how unsatisfied Helen is with their arrangement, scarcely listening to her as she makes outrageous statements to prove his lack of attention. In this sense, True Lies is part of a long line of 90s comedies about dads who work too much and need to discover the true meaning of family, from The Santa Clause to Jim Carrey’s Liar Liar.

Helen complains to her friends at work that Harry is inattentive to her needs, boring, and consumed by his work, which she believes to be computer sales. When Harry misses the birthday celebration she had planned him while he chases after the film’s terrorist villain, Aziz (Art Malik), through D.C., it seems to be the final straw. Of course, this film puts equal emphasis on the “action” in the action-comedy. A nighttime chase through D.C. gives the film its second major action sequence. It begins with an elaborate bathroom fight scene at the hotel that Omega Sector has booked for Harry under the name “Requist,” the alias he used at the Swiss party (the bathroom fight anticipates the similar one in Mission: Impossible—Fallout by over two decades). Harry’s chase involves racing after Aziz and commandeering a police officer’s horse, which he then outrageously takes up an elevator and onto a rooftop in pursuit! Aziz escapes by jumping a motorcycle into a nearby rooftop pool and, in an almost cartoonish moment, Harry and, by extension the audience, seems to anticipate that the horse can follow the jump. But of course, it can’t, and Harry finds himself dangling from the horse’s reins over the edge of the roof while the terrorist gets away. The next day we get to see some of Harry’s own office life, where he is chewed out by his boss at the agency, Spencer Trilby, played by an eye-patch-wearing, scenery-chewing Charlton Heston.

The film then puts the wheels in motion of merging the two plot lines. When Harry attempts to pop-in at Helen’s work and surprise her with a lunch date, he overhears her talking about meeting with a man named “Simon.” What he discovers is that the lack of excitement in her life has driven her to try to seek attention from the rakish and duplicitous Simon, played by Bill Paxton in one of the film’s funniest and most outrageous roles. Ripped straight from a classic comedy, Simon has a sleazy moustache and is a used car salesman who lies to women to seduce them.

The scenes between Simon and the Taskers in the film’s central portion are particularly enjoyable as they reveal the deep irony of the situation: Simon pretends to be a secret agent, even taking credit for the elements of Harry’s escapades the night before that made it into the papers, while in reality he’s a complete loser. There’s a double irony here in that it is Simon’s spy fantasies that he sells to lonely women that entrances Helen in her pursuit of excitement: a reality that her husband is in fact living without her knowledge.

Harry is driven crazy by his belief that Helen is cheating on him, and with the help of his co-worker, Gib, he uses the resources of the agency that are meant to track Aziz in order to track Helen and then Simon to determine the true nature of their relationship. In one very funny scene Harry goes to Simon’s used car lot to take a test drive of a vintage Corvette. During their drive, he gets Simon to reveal the truth about his strategy for getting lonely housewives, unsatisfied by their husbands, into bed. Paxton plays Simon as a cackling and grinning cartoon character, sleazy and cheap. He describes Helen with language that causes Harry’s rage to surge up inside (and that I’m sure raises more than a few eyebrows in a modern audience: “Ass like a 10-year old boy?” Really?). Harry imagines snapping Simon’s neck with his elbow in the seat next to him, before the film jolts us back to reality.

However, Harry does allow his jealousy and disgust with Simon to lead him against his better judgment. He interrupts an evening rendezvous between Helen and Simon with helicopters and armed and masked agents, unaware that Helen was not going to go through with the betrayal of her husband. Simon is revealed to be a massive coward, pathetically breaking down and pissing himself after being abducted by Harry and Gib. It’s a particularly dark moment of comedy. Simon is a loser and despicable man, but he really believes he is going to be killed at that moment. It’s the kind of mean-spirited comedy that pops up in this film that anticipates a lot of the humour in Michael Bay films like Bad Boys more than Cameron’s usually goofier manner. In much of the film, these elements are embodied in the character of Gib, Harry’s partner at the agency, who is mostly there for his obnoxious banter. Tom Arnold as Gib gives us most of the most mean-spirited and misogynistic moments in the film. The casting of Arnold recalls oafs from classic Hollywood comedies. He’s a throwback to an old fashioned kind of thwarted masculinity; he complains about his ex-wife being a “bitch” and makes an off-colour joke about Dana stealing money for an abortion. Of course, he is also a contrast to Harry, who will show the strength of character to eventually heal his relationship.

Harry and Gib then take Helen into custody in a mirror-walled interrogation cell, furthering her belief that Simon was a spy. They subject her to an anonymous interrogation, which ends up functioning, somewhat perversely, as a kind of marriage therapy session. Helen reveals to the anonymous Harry during her interrogation that the reason she even was taken in by Simon’s ruse is the deep unhappiness she feels in her life. As she says to the unseen Harry behind the glass wall, she “needed to feel alive.”

I just wanted to do something outrageous. And it felt really good to be needed. And to be trusted. And to be special. It’s just that there’s so much I wanted to do with this life and it’s like I haven’t done any of it. And the sand’s running out of the hour glass and I just wanted to be able to look back and say “See! I did that! I was reckless and I was wild and I fucking did it!”

Cameron understands why audiences are drawn to spy dramas, and he intuits that women enjoy the fantasy just as much as the married men he decried in his comments about Bond I mentioned above. Helen wants something different. But she also unwittingly admits to her husband that she still loves him, and always will. Harry decides then to continue to feed Helen this bit of a fantasy adventure. It's the film’s key emotional moment, but also one of the moments where the accusations of the film being misogynistic and sexist come closest to the truth. Harry’s manipulations are cruel, relying on fear and deception. His own dual life is simply the opposite of the pathetic Simon’s. He pretends to be a normal family man while actually being a spy.

One of the key elements to making the film work is that Harry must be upright as well as culpable in the failure to balance his two lives. Schwarzenegger manages to combine competence with a naivete that is key to selling the role; there’s a lot of mugging and eye rolling or bugging out in this movie, when Harry is flabbergasted or enraged. He functions as a counterpart to Curtis as Helen; each imagines themselves to be living a life that is different from the one that they are. This culminates in what is perhaps the film’s most famous sequence, Jamie Lee Curtis’s hotel striptease in front of a man she doesn’t realize is actually her husband. Some critics, including Roger Ebert, called the sequence “cruel and not funny,” wallowing in humiliation and nastiness.

There is an element of truth to the fact that Helen doesn’t really get to have power in this situation, with Harry exploiting the reality of the situation to try to heal his marriage. It’s discomforting for the audience and misguided on his part. But at the same time, it’s not as simple as the detractors make it out to be, and the striptease scene, which Ebert thought better on the cutting room floor, is one of the film’s most memorable and famous moments for a reason.

Curtis plays the scene perfectly as a woman both excited and scared by the job she has to do. Entering the hotel suite, she nearly trips in her high heels. Harry, shadowed in the window, uses a recording by his French colleague, Jean-Claude (a reference to Arnold’s erstwhile European action movie rival) to give his wife instructions (we have to buy into the idea she wouldn’t recognize him even in silhouette). But the scene is also the one where the cards begin to turn against Harry, and we get to see the competence and development of Helen’s bravery.

Curtis makes the scene work, making it funny and awkward, but also genuinely sexy. Curtis herself had significant input into the development of sequence. The original version of the script had her doing the striptease naked, but in silhouette, concealing the most explicit nudity. But Curtis convinced Cameron to do it differently, by surprising him in the office and doing the dance for him in her underwear. The scene is delivered with a massive wink to the audience, including a moment when Helen slips in the midst of her impromptu pole dance lest we take it too seriously. Helen even gets the better of Harry, hitting him over the head with a telephone after he tries to kiss her, still not realizing it’s him, as she begins to rush away with him pleading with her on the floor. Harry’s deception results in his punishment and the realization that he cannot deceive her and control her forever.

The sequence also is the hinge point of the film, merging the spy and domestic plots as Harry and Helen’s game is interrupted by Carrere’s art dealer, Juno Skinner, who abducts Harry and Helen and takes them to the terrorist Aziz. Just as in The Abyss, the domestic plot and the action plot merge.

Aziz forces Harry to reveal that he’s a spy in front of Helen so he can confirm for the world that he has possession of a nuclear warhead. Aziz and his Crimson Jihad might seem to be the worst caricature of Islamic terrorism. He gives an impassioned speech on tape (before his cameraman explains the battery died) explaining their position:

You have killed our women and our children, bombed our cities full of fire like cowards, and you dare to call us terrorists. But now the oppressed have been given a mighty sword to strike back at their enemies. Unless the US pulls all military forces out of the Persian Gulf immediately and forever, Crimson Jihad will rain fire on one major US city each week until our demands are met.

Essentially, there’s nothing Aziz says about what the US has done to countries in the Gulf region that’s untrue. Additionally, Aziz is first threatening to detonate the nuke in an uninhabited island in the Florida Keys, as a gesture of good will to show they mean business, which is more than one can say for many other world actors. The film’s portrayal of Islam, as a convenient post-Cold War villain, is a relic of a pre-9/11 world where that portrayal didn’t seem so real and frightening, in either its consequences as real danger to the U.S. or to the vast majority of Muslims in the world stigmatized by it. Nonetheless, Cameron includes a “good” Arab character, Harry’s ally, Faisil, the Omega Sector operator I mentioned above. The film makes it clear that Aziz doesn’t speak for all of Islam.

The finale of the film involves Helen and Harry teaming up to stop the terrorists and get off the island before the nuclear weapon goes off. The action sequences of the film’s last third are excellent, including the memorable moment Harry uses a gas tank to create a flamethrower, but they also incorporate slapstick humour and make Harry such a ridiculously powerful secret agent that it’s impossible to take it all with a straight face. Cameron rightly realizes that his strength is in action, and so is most successful in generating humour by being more over the top and outrageous than ever. True Lies is a film that in some ways is the closest to a Michael Bay-type film that Cameron would ever make, anticipating some of the trends in action movies later in the decade in both its crude humour and action.

But even as we laugh and are thrilled, the finale of the film forges the reunion of Harry and Helen’s marriage in the the moment when Helen grabs onto Harry’s hands and she is pulled from the limousine moments before it goes over the bridge. The moment is both over the top—the uniting of hands is hardly subtle—and genuinely thrilling. True Lies is as much a spectacle as any of his films, with an action finale on top of a high rise where Harry dispatches the villain on a missile. The sequence even includes a classic Schwarzenegger one-liner, as he declares “You’re fired” before shooting the missile. But it’s also another film from Cameron where the real heart of the film is in the romantic relationship and the bonds of family and love, a theme that would continue through all his films.

True Lies isn’t as groundbreaking and boundary pushing as nearly every other James Cameron film is, but it’s successful in bringing together many of Cameron’s thematic interests, particularly the centrality of romantic and familial relationships to his films, along with the action comedy. Few films billed as straight action-comedies would imbue the action with as much emphasis as the comedy. Stylistically the film is different from his earlier films—Cameron utilizes a much more polished look in this film than his earlier films, with a warm colour palette, and widescreen anamorphic composition that has lots of medium-close ups. In some ways it reminds me of a Hong Kong film in the way it balances tonal shifts between pure action, slapstick comedy, and sentimental romance.

It's probably accurate to say that True Lies is the weakest film he ever did (apart from Piranha II, if we need to keep acknowledging that one even exists). While it didn’t make as much money as Terminator 2, it was the third highest grossing film domestically of 1994 (after The Lion King and Forrest Gump), bringing in $146 million and $378 million worldwide. It’s undeniable it was still a popular film. Some of the jokes don’t land and Tom Arnold can get irritating as Gib, but it’s also more generous towards its villains (well, except for Bill Paxton’s slimy Simon) than many Hollywood action films. I never get bored rewatching True Lies, and it's also a very fun movie if you can embrace the over-the-top nature of it. Ultimately, it also has some real truths about the challenges of maintaining a marriage relationship over the long haul. It highlights and elaborates on the little deceptions and half-truths that creep into a relationship over time. Maybe it’s not an affair or a double-life as a spy, but simply the desire to carve out some space for one’s self. The film also displays a faith in family and marriage that few films of its kind actually do. Its resolution is essentially that the family that spies together, stays together. If this is the weakest film you’ve ever made, you’re doing a lot of things right.

8 out of 10

True Lies (1994, USA)

Directed by James Cameron; screenplay by James Cameron, based upon a screenplay by Claude Zidi, Simon Michael, and Didier Kaminka; starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, Jamie Lee Curtis, Tom Arnold, Bill Paxton, Tia Carrere, Art Malik, Eliza Dushku, Grant Heslov, Charlton Heston

George More O’Farrell’s The Holly and the Ivy is a perceptive Christmas drama that deserves a place in the Christmas rotation.