Review: Take Out (2004)

Sean Baker’s debut feature, Take Out, co-directed by Shih-Ching Tso, which debuted at the Slamdance Film Festival in 2004, heralded the arrival of a strong directorial voice in American independent cinema. With dialogue almost entirely in Chinese, Take Out tells the story of Ming (played by Charles Jang), an illegal immigrant from China, living in New York City’s Chinatown, who must raise $800 by the end of the day lest the smugglers who got him into America double the debt he owes them.

From the start, Baker, and co-director Tso, who went on to produce many of his later features, show an interest in documenting the lives of those who find themselves on the margins of society, whether by choice or necessity. While most of Baker’s later films explore sex workers (and despite the trendy nomenclature, Baker really is interested in the economic elements—the work—of the lives of escorts, porn stars, and strippers), Take Out is about a delivery person, albeit one without legal status in America. This binds Ming to Baker’s later subjects by showing some of the ways he is vulnerable, beyond the protection of the law and at the mercy of the moral censure of others.

In the twenty years since Take Out appeared, the delivery person has become an even more familiar face in contemporary North American life, in the age of Ubereats and Doordash. Baker’s characters go beyond being merely portraits of prurient curiosity and instead point our attention to modes of life in contemporary society, such as that of the gig worker with precarious employment. Take Out, with its focus on immigrants and food delivery, is more relevant today than ever.

In Take Out, Baker isn’t just interested in subject matter and themes though. This is what separates Baker from other contemporary directors who showcase poverty or taboo subjects. His social-realist style utilizes strong storytelling instincts to draw attention to the socio-economic conditions of his characters. His films have stakes and narrative structures that draw the audience’s interest cinematically

Ming has come to America from China and settled in New York City’s Chinatown, working for Big Sister (Wang-Thye Lee) as a delivery person in a Chinese restaurant. We learn that he has come to America hoping to find a pathway to legal residency and to bring his wife, and the child whom he has never met, to join him. As the film begins Ming is confronted by his smugglers who got him into New York over the Canadian border. They demand that he pay them $800 by the end of the day or else they will double the debt he owes them. Thus, the film sets up a clear timeline and stakes. Ming borrows some money from a relative, but he needs to find the difference, around $500, through tips and working non-stop all day, delivering Chinese food in the rain, navigating the Manhattan streets on his bicycle.

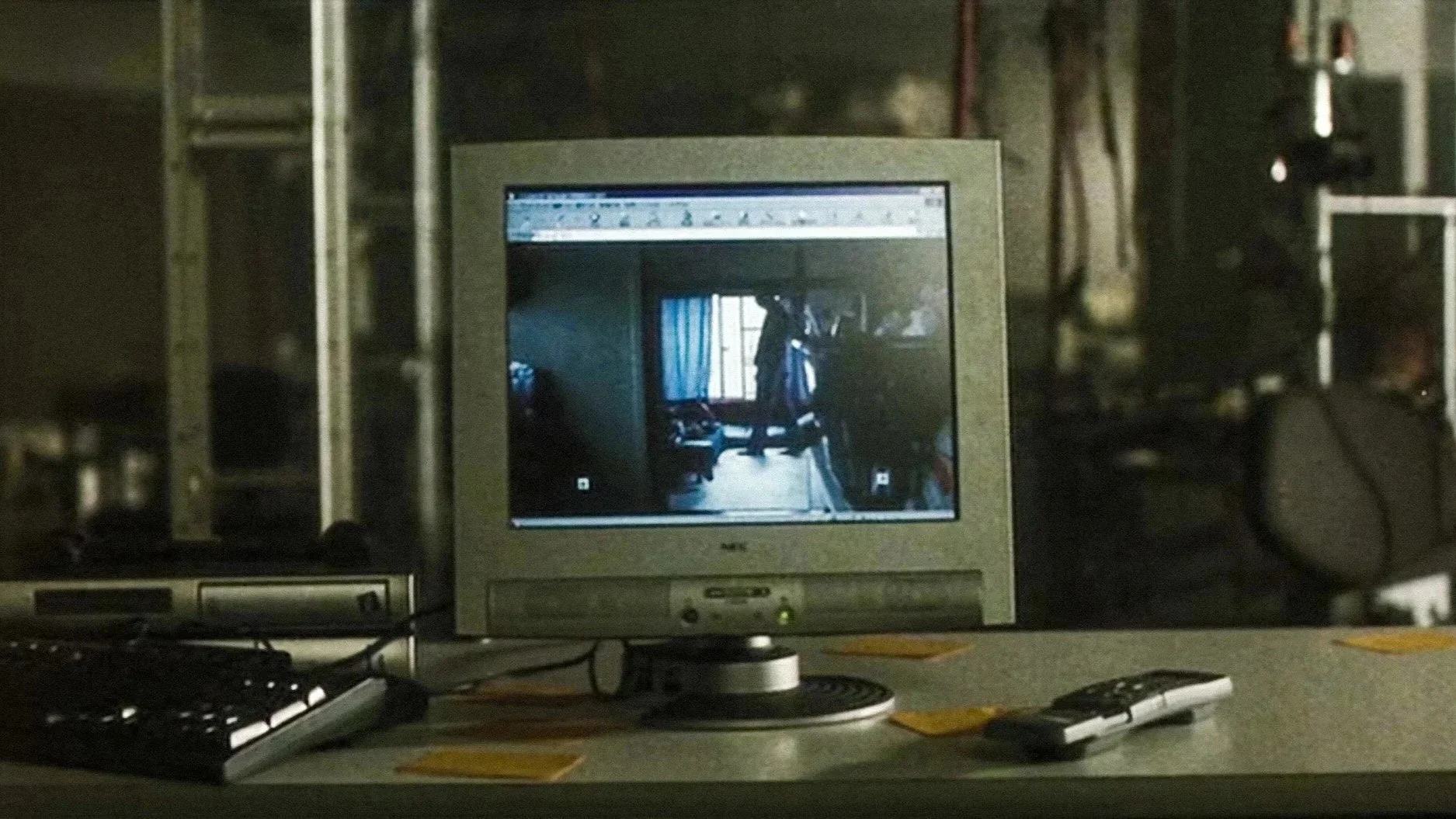

The film has a very naturalistic style and is shot on early-2000s digital video. It lends the film a documentary feel that isn’t just window dressing and is maintained throughout. At moments, one could easily be convinced you were actually watching a documentary, if not for the unlikelihood of the camera finding such a story and witnessing some of the things it does. Baker and Tso’s digital camera captures the milieu perfectly. The qualities of early digital video allow the filmmakers to capture images in darker environments without the longer exposures that would be necessary on handheld film, especially when shooting in low light or fluorescent- and neon-lit nighttime scenes. It recalls some of the work of Taiwanese master Hou Hsiao-hsien in the early 2000s, particularly Millenium Mambo (a film which in different ways also anticipates some of Baker’s later films, including 2024’s Anora).

Take Out spends a lot of time showcasing the repetitions of the day that structure work in the Chinese restaurant. For instance, the film shows the way Ming’s fellow workers light the burners and take orders and the way Ming locks up his bike and heads up the stairs of the cheap apartments all over the Lower East Side. We meet all kinds of customers who are upset when he’s late or when the order is wrong. One customer, who asked for chicken and not beef, is played by regular Baker collaborator Karren Karagulian (Toros in Anora). At times we sense that Ming is actually in danger. There is suspense and deep discomfort. The delivery man is often given a quick peek into the intimate lives of those he is delivering food to, while they remain oblivious to his predicament. We are put in the perspective of the delivery person, not the customer who sees him for all of a minute or two. When put in the context of Ming’s repetitive day, it offers a very different portrait of the job.

The film also highlights the conversations between Ming and his co-workers, most of whom also made their way to America illegally. They comment on the increasing difficulty of both entering and remaining in post-9/11 America. The spectre of 9/11 hangs over the film in ways beyond the War on Terror. For example, the cook, Wei (Justin Wan), wears a “United We Stand” ballcap. Some have found permanence and others are still in the midst of paying off their debts. As his co-worker Young (Jeng-Hua Yu), a happy-go-lucky and humorous character, tells Ming in one quiet moment when Ming is looking particularly downtrodden, “It will all pay off.”

And that truism, that all the degradation and hard work will “pay off,” is taken for granted by almost every character in America that Baker features in his films. Everyone is hustling, looking for the payoff that will deliver them from their current life. The system that exists tells everyone that they are special, that they can circumvent the rules, that their dreams and personal motivation will deliver them up. How can this be possible? Is the payoff worth it?

Ultimately, with Take Out, Baker reaches for and succeeds in delivering both gut-wrenching pathos and small moments of grace. In one arresting moment, we see Ming pause in a corner and take out the small photograph of his wife and child that he carries with him. The soundtrack cuts out, and in that silence we understand Ming’s motivation and how he keeps going through the abuse and exhaustion.

For all its grittiness, Take Out may be one of Baker’s most hopeful films. A portrait of the early 21st century shot with an unflinching attention to detail, it heralded the arrival of a major American independent filmmaker and is well worth seeking out.

9 out of 10

Take Out (2004, USA)

Written and directed by Sean Baker & Shih-Ching Tso; starring Charles Jang, Wang-Thye Lee, Justin Wan, Jeng-Hua Yu.

George More O’Farrell’s The Holly and the Ivy is a perceptive Christmas drama that deserves a place in the Christmas rotation.