Review: The Woman in the Window (2021)

There’s a medical condition called nystagmus, which causes a person’s eyes to uncontrollably move back and forth or even roll back into his or her head. The condition can be congenital or caused by various medical events and diseases, such as epilepsy, stroke, fainting, and multiple sclerosis. Might I suggest viewing Joe Wright’s The Woman in the Window be added to the list of potential causes? This preposterous thriller, based on the derivative novel by A. J. Finn (the pseudonym of author and serial liar, Daniel Mallory), has an abundance of talent in front of and behind the camera, but is an agonizing experience that will provoke derision and uncontrollable eye-rolling throughout. It’s a film that demonstrates an irrational confidence in the ideas that Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) is too slow, that only trauma motivates female characters, and that you shouldn’t let things like coherence and thematic cohesion get in the way of a shocking left-field twist.

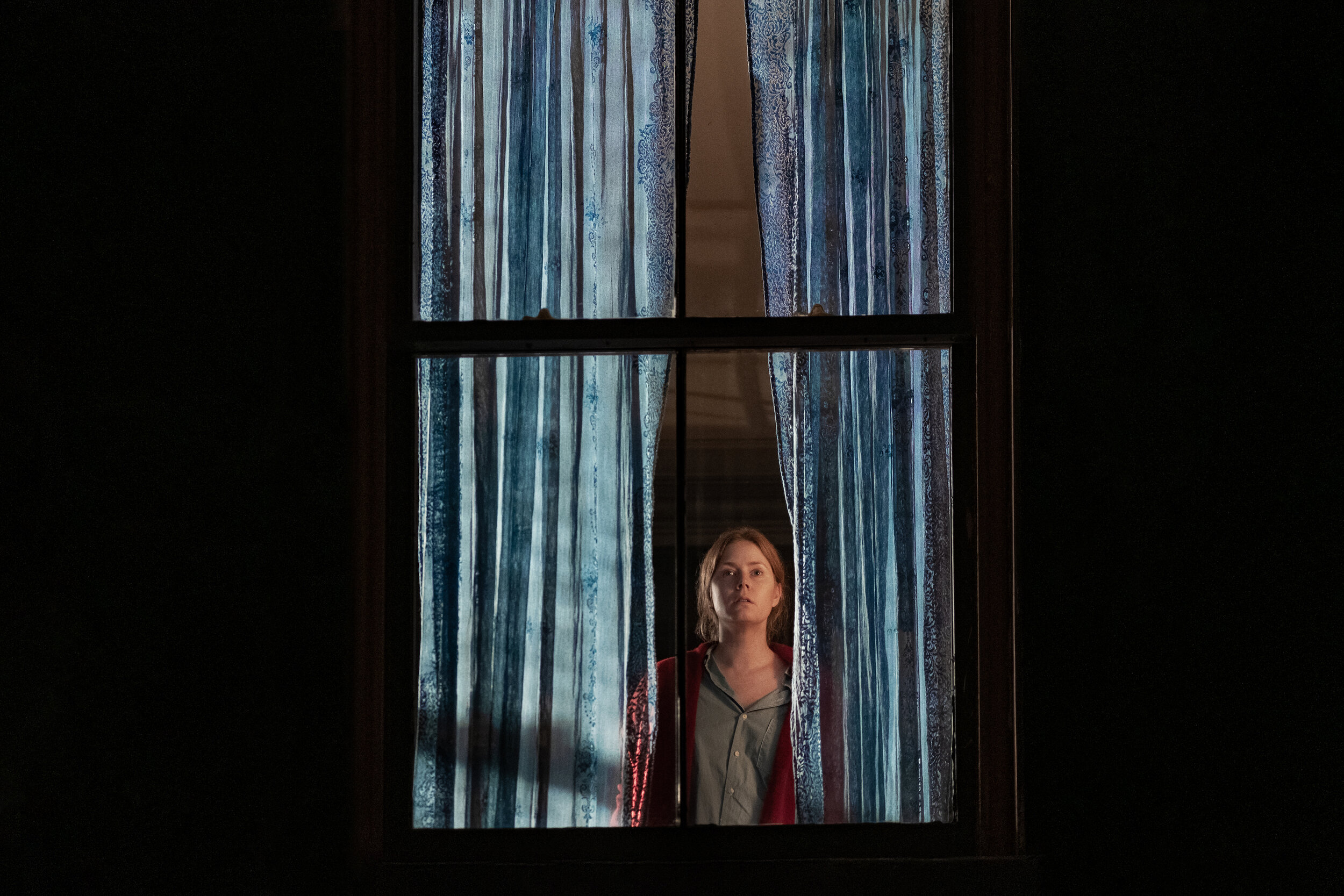

Poor Amy Adams, one of the best actors of our era, stars as Anna Fox, a psychologist suffering from agoraphobia and confined to her Manhattan brownstone, away from her husband (Anthony Mackie), from whom she’s separated, and daughter (Mariah Bozeman). Anna drinks too much, pops various pills, and warily watches people across the street through her window, which combined with her agoraphobia makes her something of an unreliable protagonist.

When she befriends Jane Russell (Julianne Moore) and her son, Ethan (Fred Hechinger), the new neighbours who move in across the street, and then one evening spies the abusive father, Alistair (Gary Oldman) murder Jane through the window, the cops (Brian Tyree Henry and Jeanine Serralles) and everyone in Anna’s life such as her downstairs tenant (Wyatt Russell) are not prone to believe her. The appearance of another woman (Jennifer Jason Leigh) claiming to be Jane Russell puts the icing on the cake: is Anna crazy or did she really witness a murder?

The entire set-up is a familiar one, taking cues from Hitchcock’s Rear Window and recent bestselling novels like Paula Hawkins’ The Girl on the Train. Anna herself is a familiar twist on one of Hollywood’s favourite female protagonists, the hysterical woman who cannot be trusted due to her various ailments and societal sexism in general. Director Joe Wright knows that he’s working with generic material and foregrounds the allusions and references in the film. In the opening credits, we see a still frame from Rear Window, while another scene shows the famous dream scene from Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945) playing on the television. The writing also leans into the pseudo-feminism that’s popular in contemporary Hollywood pictures, drawing on a deep cinematic well going back to Gaslight (1944). None of these generic elements is individually the problem, but the total effect when combined is to create a film that is entirely derivative.

The largest problem with The Woman in the Window is that everything that happens in the film is baffling. The film never develops tension regarding its central mystery, never causes us to doubt Anna’s reliability, and never produces satisfying answers to its many, many questions. It relies on rehashed plot developments to substitute for calculated structure and gestures at social issues instead of developing depth for the characters. Mostly, it relies on its stacked cast and talented key crew members to make up for the abysmal narrative construction of the source material. It’s all a case of putting as much lipstick on a pig as possible.

There’s Joe Wright, a director known for Atonement and Darkest Hour and who is usually a sure hand with prestige affairs, seemingly allowing his anxiety over the shoddiness of the material to motivate him into overcompensating with a hyper-stylized visual presentation. He pulls out as many formal tricks as he can to make the film look “interesting,” from canted angles to bleary and oversaturating tinting on scenes meant to capture Anna’s frayed reality to a recurring visual motif of snowflakes blowing in a vortex, which ends up revealing aspects about Anna’s traumatic past. It’s a film hyper-stylized to within an inch of its life.

There’s Tracy Letts, who wrote the screenplay—yes, that Tracy Letts, who won the Pulitzer for August: Osage County and is a beloved Chicago stage actor with appearances in films like Lady Bird (2017) and even a small part in this one. He does nothing to enliven the dreadful source material and instead plays everything as fast as possible in an apparent effort to mask all the plotholes and implausibilities that pile up over the course of the film.

There’s Danny Elfman, who provides the obtrusive score that underpins every innocuous action with malicious intent, turning small moments in the film into laughably histrionic presentations. There’s cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel, who does his best to transform the home into a haunted space, but ends up imbuing every scene with visual cliche. And then there’s the stacked cast, including Adams, Oldman, Mackie, Russell, Henry, Leigh, and Moore, all actors capable of nuance and genuine dazzlement on screen, but who seem hopelessly incapable of making this material work.

The perplexing nature of the film can be summarized in the scene immediately following Anna calling the cops to report Jane Russell’s murder. Anna tries to leave the house to save Jane, but she blacks out under the mental pressure. When she comes to, the two detectives are in the home and tell her that a murder didn’t happen. She tries to convince them, but they tell her that Jane Russell is alive and well and open up Anna’s door to reveal: voila, Alistair and “Jane,” now played by Jennifer Jason Leigh. Because, yes, when you call the cops on someone to report a murder, they invite the person you’re accusing into your home to berate you in front of them. As if this scene alone weren’t absurd enough, the film doubles back to this exact set-up multiple times throughout, with each subsequent appearance of the detectives provoking another appearance from Alistair who bursts in through the front door to yell at Anna, as if the cops had given Alistair the keys to her property while dealing with the fallout of her 911 call. It’s a bit much to take, to put it lightly.

The Woman in the Window is a film that is cynically calculated into oblivion. It has the creatives and the cast of a potentially great film, and a conceit that tries to tap into fruitful narrative and thematic aspects of Hollywood thrillers, but it ends up being all the more preposterous and insufferable for how empty all these elements are. It’s fitting that Netflix picked up the film after it was removed from the theatrical schedule because of the pandemic. It’s the ultimate example of a film calculated to be “content,” an appealing idea with actors you like and by filmmakers you respect that will make 100 minutes go by without incident. The fact that it’s the number one film on Netflix as I write this and that I was goaded into watching it by the algorithm shows that it’s done its job. The cynical calculation of the film has pulled in the necessary eyeballs and generated the needed viewership to move a decimal point to the left on Netflix’s profit margin. But that doesn’t mean I need to enjoy the empty process. Sometimes, you can just call trash “trash” and leave it at that.

2 out of 10

The Woman in the Window (2021, USA)

Directed by Joe Wright; written by Tracy Letts, based on the novel by A. J. Finn; starring Amy Adams, Gary Oldman, Anthony Mackie, Fred Hechinger, Wyatt Russell, Brian Tyree Henry, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Julianne Moore, Jeanine Serralles, Tracy Letts, Mariah Bozeman.

This mockumentary starring Matt Johnson and Jay McCarrol is a complex metafiction farce and a loving portrait of friendship and Toronto.