Review: It Comes at Night (2017)

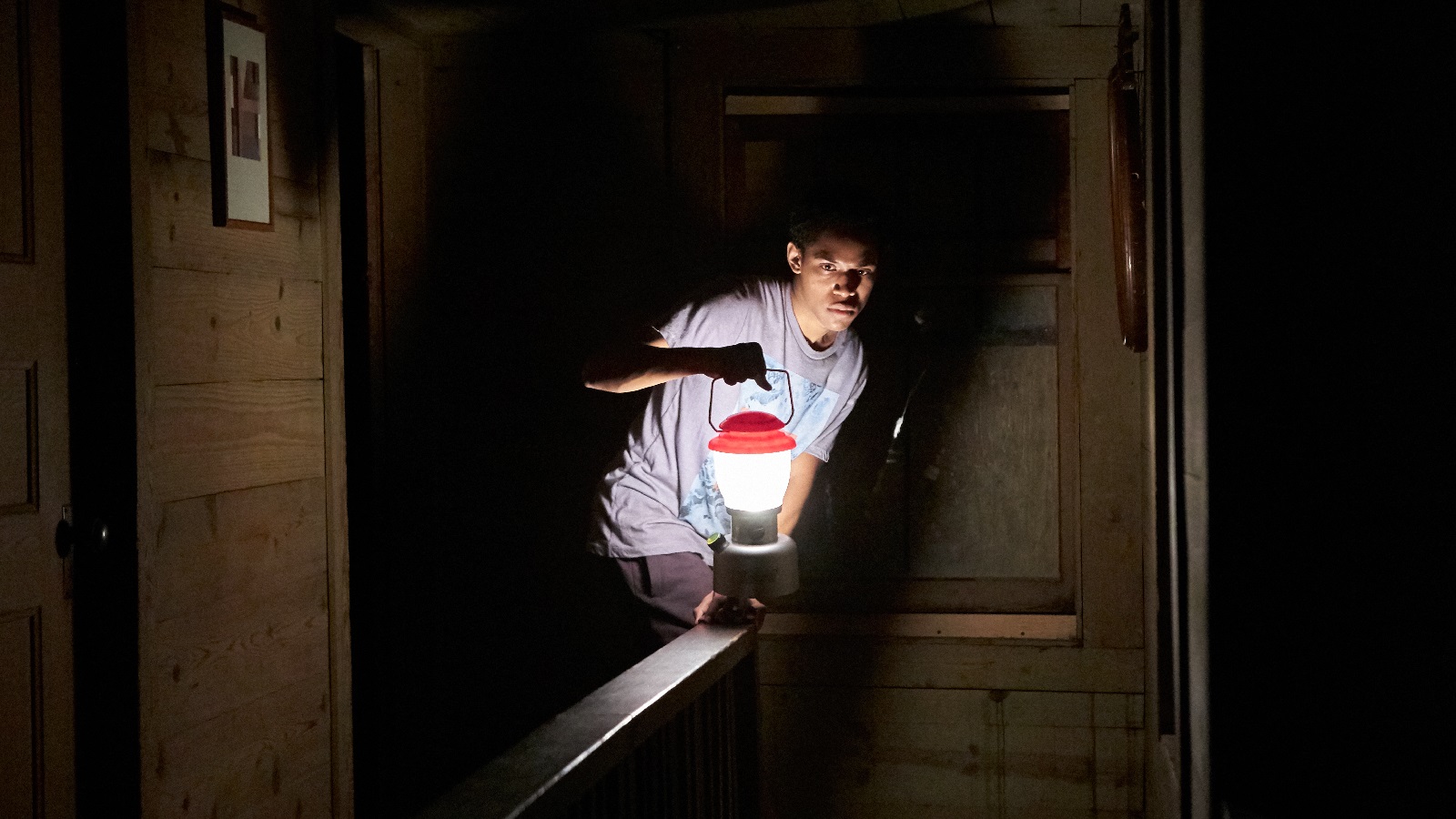

Trey Edward Shults’ It Comes at Night perfectly demonstrates the limits of formalism. It is a beautifully-shot horror film that uses various aspect ratios and narrow depth of focus to conjure a chilling visual tone. It is well acted, especially by relative-newcomer Kelvin Harrison Jr. and Joel Edgerton, who is something of an unsung talent these days. It is frequently creepy and cleverly uses unique editing rhythms in its portrayal of dream sequences and uncanny nighttime events. And yet it fails as a horror film because it is nothing but exceptional technique in service of a story so rote, anyone who has seen 10 minutes of The Walking Dead could write the ending.

It Comes At Night follows a family (Joel Edgerton, Carmen Ejogo, Kelvin Harrison Jr.) living in a house in the woods after an apocalyptic event. They encounter a man (Christopher Abbott) breaking in during the night and make an uneasy truce with him, inviting him and his family (Riley Keough, Griffin Robert Faulkner) to come live with them in their barricaded home. Although the union initially flourishes, tensions rise as mysterious happenings in the wood encroach on their safety.

Writer and director Shults, who previously directed the indie-darling Krisha in 2016, clearly intends It Comes at Night as a meditation on grief and loss. According to interviews, he came up with the idea for the film after the death of his father and was inspired by the paintings of Bruegel (a personal favourite of mine and touchstone for filmmakers from Tarkovsky to von Trier) in the film’s dream scenes and apocalyptic concept. He also drew on the influence of one-time young formalist hotshots, and cinephile favourites, like Stanley Kubrick and Paul Thomas Anderson; you can see this in the controlled camera movements, the deliberately-confused geographic space of the home, and the meticulous framing of human faces.

Shults is a director with talent and good taste. He doesn’t want his films to merely be promising; he wants them to be great. Which is why it’s such a shame he tries to conjure a stunning, artistic statement out of a story that’s been told a thousand times. Post-apocalyptic storytelling is old-hat at this point and it’s hard to stand out from the popular works like The Walking Dead. Shults attempts to stand-out by underplaying everything. He doesn’t give exposition about the nature of the apocalypse. He never shows the monsters in the woods. He doesn’t let the characters sort out their feelings in a rush of words, aside from one nighttime conversation in the kitchen.

But understatement isn’t always the right move for horror. It’s true that off-screen space is more terrifying than on-screen space (I’ve said as much in my many reviews of found-footage horror films), but there has to be the possibility of terror, the presence of violence, the ability for things to go spiraling out of control, if we’re to take the threat of the off-screen space seriously. Perhaps we’re not meant to take any of the physical happenings in It Comes at Night seriously. Perhaps it’s all meant to be psychological and the real horror is Joel Edgerton’s quick acceptance of brutality to deal with any threats to him and his family. But as far as The Shining rehashes go, Mike Flanagan’s Oculus was scarier and more convincing as a descent into madness.

It Comes at Night is often beautiful and atmospheric and interesting, but it is not scary and it is not exciting. It is minimalism in a maximalist genre. It whispers “Boo!” so quietly in an effort to scare us with silence, but instead it leads us to wish it would speak up.

Subtly has its place in filmmaking, but in a horror film that retreads familiar narrative ground, it can prove fatal.

5 out of 10

It Comes at Night (2017, USA)

Written and directed by Trey Edward Shults; starring Joel Edgerton, Christopher Abbott, Carmen Ejogo, Kelvin Harrison Jr., Riley Keough, Griffin Robert Faulkner.