Review: The Day After Trinity (1981)

Viewers who want to dig deeper into the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer and the development of the atomic bomb should seek out Jon Else’s 1981 Oscar-nominated documentary, The Day After Trinity. Narrated by the booming voice of actor Paul Frees, Else’s film is a somber, sober examination of the Manhattan Project and the moral responsibility conveyed by Oppenheimer’s scientific breakthrough. Watched in the wake of Christoper Nolan’s Oppenheimer, the film provides an intriguing nonfiction counterpoint to Nolan’s epic biopic, as it forwards many of the same ideas, but through a hushed tone that’s about as far from the stylistic assault of Nolan’s film as you could get.

Interviewing key Manhattan Project scientists, including Hans Bethe, Robert Serber, Robert Wilson, Richard Feynman, and Frank Oppenheimer, brother of Robert, as well as close personal friends, including the leftist Haakon Chevalier, the film spends 88 minutes documenting Oppenheimer’s life and career, particularly his work on the atomic bomb. The Day After Trinity finds its thesis in the comments made by Frank Oppenheimer when asked about his reaction after hearing of the bombing of Hiroshima. Frank remarks that his first, instinctive reaction was to say he was glad the bomb worked, fearing their work was for naught, but then he felt deep waves of guilt and an intuitive understanding that the bomb should’ve never been used.

This tension between the desire of the scientist to see his experiment succeed and the philosopher’s fear of what comes in the wake of such success sums up the life of Oppenheimer better than most other statements I’ve heard; it’s fitting that it’s his brother who expresses such remarks. The most rewarding aspects of The Day After Trinity are its interviews of Frank Oppenheimer, Hans Bethe, and other esteemed individuals who were close to Oppenheimer and his work. Simply hearing their thoughts on the epochal ramifications of the Manhattan Project are worth the viewing. But there’s more to the film than simple historical documentation.

Through the patient accumulation of interview footage, declassified photographs, and footage of atom bomb testing as well as the aftermath of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the film creates a terrifying, nonfiction portrait of the world we entered with Oppenheimer’s breakthrough. Perhaps most startling is the short sequence documenting Robert Serber’s visits to Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the months following their devastation. Footage of Serber and crew wandering around the decimated husks of the cities, free to examine any ruin, any street, any spot they wished, is haunting, a kind of depiction of men traversing hell. But it’s also illuminating of how the human cost of their work only became apparent to the Manhattan Project scientists in the aftermath of its success. Serber’s comments that the Japanese people he met who were suffering from radiation burns and other wounds from the bombings didn’t express any anger at him speaks volumes to this fact. Such remarks bring the human dimension to the fore, transforming statistics into human beings with their own stories to tell.

The film’s finale features a montage of atomic explosions, including the apocalyptic detonations of hydrogen bombs, developed by Oppenheimer’s colleague and eventual rival, Edward Teller. The footage is impressive, awesome, terrifying. It justifies Oppenheimer’s rather pompous declaration from the Bhagavad Gita following the Trinity test: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” A man who unleashed such power clearly understood that his power was that of a god, and his moral culpability the same.

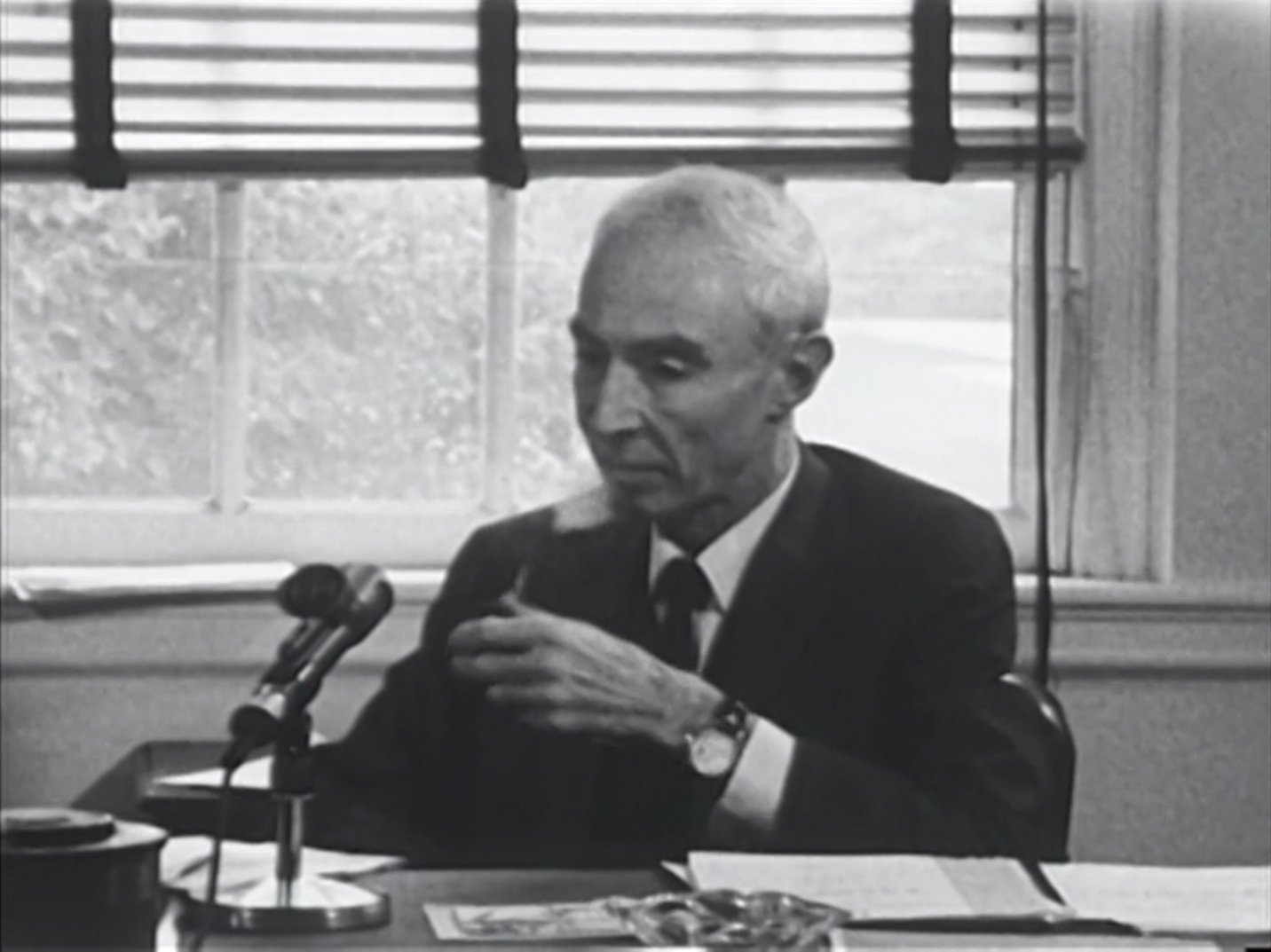

Else’s film ends with footage of Oppenheimer giving the quote that gives it its title. After being asked about his thoughts on Bobby Kennedy’s work to encourage Lyndon B. Johnson to seek nuclear de-proliferation, Oppenheimer says that “It’s 20 years too late. It should have been done the day after Trinity.” Nolan’s film ends with a similarly damning statement, but hearing it from the man himself makes clear that Oppenheimer was sure of his legacy, one we continue to struggle with—and live in the shadow of—to this day.

8 out of 10

The Day After Trinity (1981, USA)

Directed by John Else.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s 2001 J-horror film predicted the new millennium in terrifying ways.