Roundtable: Oppenheimer (2023)

Aren: It’s been several weeks since the now-famous twin release of Barbie and Oppenheimer, the so-called Barbenheimer weekend, which has proven to be the first sustained instance of monoculture since the pandemic. Top Gun: Maverick and Avatar: The Way of Water were both more successful as individual releases, but they weren’t events in the same way. People are comfortable going to see movies again and folks feel compelled to seek out both a film based on a children’s toy and a three-hour biopic about the father of the nuclear bomb just to be a part of the conversation. It’s impressive and I’m glad to have so many people invested in going to the movies as an event again.

Anders: It’s definitely nice to have movies at the centre of the cultural conversation. It does seem like these two films have saturated popular consciousness in a way that the television shows and film releases of the last three years were never really able to do.

Anton: I think the Barbenheimer weekend itself is the defining feature, even if both these films continue to do excellent business. As you suggested, Aren, Top Gun: Maverick and Avatar: The Way of Water each overwhelmed and sustained whole movie seasons, whereas both Barbie and Oppenheimer became a particular event with their opening weekend. I can’t remember the last time regular people, I mean non-movie-buff types, were talking to me about opening dates and predicting the box office numbers. If Top Gun: Maverick saved theatrical exhibition after the pandemic’s shift to streaming, then Barbie and Oppenheimer have made movie opening weekends an event again.

Anders: But I also wonder if by making these films all about the experience, the “fear of missing out,” and the pageantry of dressing up, people are shortchanging the films themselves. I guess this is an opportunity to talk about the film beyond the hype and the moment itself.

Aren: Yeah for sure. We’re going to focus on Oppenheimer here—you can read my mildly positive Barbie review to get my thoughts on that one. Oppenheimer is a towering film. I’m an out-and-out Christopher Nolan fan at this stage, but even from a director whose films I love, I found Oppenheimer to be one of his best.

Just on the public reception for a moment, I’m impressed that so many people are invested in a film that is genuinely difficult in many senses. For one, it’s a historical film, and people nowadays are infamously ahistorical. It’s also a film with a radical editing style, relying on pure montage for long sequences. It’s dark, with a haunting ending that left me troubled for days after seeing the film—read Bilge Ebiri’s great piece at Vulture for a longer discussion on the ending, which apparently left some people who saw the film gasping with tears. And, most obviously, it’s three hours long! A movie like this is not a typical blockbuster in our current age, and yet Oppenheimer is on track to be Nolan’s biggest non-Batman movie. That’s very impressive.

Anders: Walking out of the film, I definitely felt it was one of Nolan’s strongest films. Now, I generally have a positive reaction to Nolan’s films, but this felt a bit different. It wasn’t some mind-blowing twist, but it was, as you note, the feeling that I’d gotten a glimpse of something about the history of the last century that I hadn’t quite comprehended. It’s an occult history, something that Nolan often leans into in his films, but one based not only on the hidden secrets of men but the secrets our physical world contains. It’s well worth digging into.

Anton: I’m also a huge admirer of Nolan. Half of one of the regular university courses I teach is focused on Inception and his works! But, of the three of us, I’m probably the least enamoured with Oppenheimer after my single viewing—even if my 9/10 review doesn’t really suggest a muted response! I’m not sure I consider it one of his top films, but, as I also say in my review, I have to sit on the movie a bit more and definitely see it another time.

I felt similar about Dunkirk, which I did not love—but quite liked—when I first saw it. But I’ve grown to admire it more and more.

Aren: I think Dunkirk might be Nolan’s best film, so that explains why I’m so high on Oppenheimer.

Anton: What I will say is that I think Nolan is consciously pushing the envelope of his cinematic approach, which is already known for pushing the envelope of things. And most of Oppenheimer certainly pays off. I’m just not ready to declare it his masterpiece, and I’m also in the minority that thinks Tenet was by no means a misstep or a weak entry for Nolan.

Aren: Tenet was my top film of 2020! Albeit, that was an odd year for movies, but I raved about that movie and have seen it a bunch of times. It’s clear we’re all Nolan fans.

Anders: To clarify, I really think Oppenheimer is something special, but I also find, as you note, Anton, that it takes some time for my feelings on Nolan’s films to coalesce and settle. For instance, I was more muted on Interstellar the first time I saw it, but now it might be my favourite Nolan film.

Aren: Okay, back to the film itself. Anton, you’ve already written an excellent review of Oppenheimer, but I thought we could have a more free-flowing conversation about the movie and certain aspects of it. I’ve seen it twice now, once in digital IMAX (not a lieMax), and both times I’ve been overwhelmed by both the furious pace and the wealth of information that the movie conveys. Oppenheimer covers a lot of story and has a huge amount of historical information, but at its heart, it’s not a conventional historical film. It’s a tragedy and a moral investigation of J. Robert Oppenheimer, told through the frame narrative of two investigations taking place over the course of two timelines—one shot in black and white and the other in colour. Those two investigations also jump around all over the place. But despite all that, the movie has a clear throughline emotionally, and has an incredible amount of tension, despite us knowing generally how all the individual elements are going to end.

Anders: I’ve only seen it one time, in IMAX, and I really can’t wait to see it again. But nonetheless, I agree that there’s a clear emotional and narrative throughline. Nolan is known for manipulating time in his films, and I expected this film to jump around chronologically, but it doesn’t feel like a puzzle, but rather the logical way to tell the story. I felt like I did get what he was going for in his telling. It clicked for me and I wasn’t confused.

Aren: As well, I just have to say, Oppenheimer is incredibly fast paced for a three-hour movie. And despite people mocking Nolan for his dourness, the weight of seriousness he brings to this film is so appropriate to Oppenheimer the man and the subject matter of the atom bomb. This is one of those movies of such complexity where there are probably only half a dozen directors in the world who could manage such a thing.

Anton: Yes. I truly believe few filmmakers right now could execute this film. Oliver Stone gave Nolan some huge props, I’m not sure if you saw. And Paul Schrader said it is the best of this century!

Anders: I did not see that, but Stone’s comments make sense given how one of the touchstones I marked for this film on my first viewing was JFK.

Anton: Yes, both films make conversations into action scenes and stitch the many and complicated events into sophisticated montages. Not to mention the interplay of colour and black-and-white, which is a hallmark for Stone.

I mentioned in my review that I really liked the movie but that I do think a second viewing would help to clarify aspects of my evaluation. I agree that the movie is pretty fast-paced, but I wonder if it is also somewhat unwieldy.

Lastly, maybe I’m just dour myself but I honestly don’t understand the constant complaint that Nolan is too serious, too sombre, etc. This is a movie about the making of the atom bomb! What the hell? I want this one to be dour and serious. Nolan also made Batman movies, not Spider-Man. Come on!

Oppenheimer’s Biopic Conventions & Character Drama

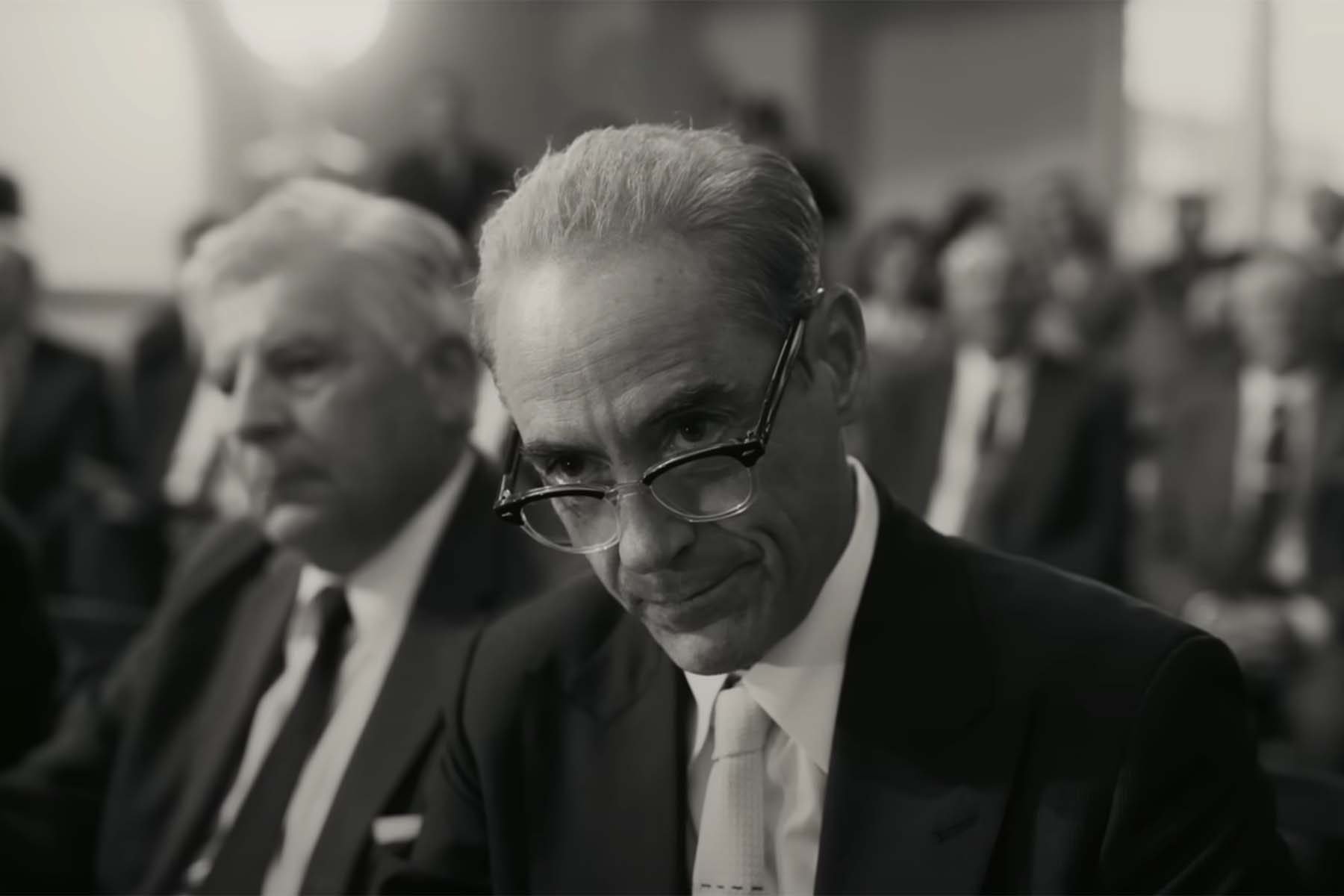

Aren: Probably more than any film of Nolan’s since Memento, Oppenheimer is carried by a titanic central performance—and bolstered by some exceptional supporting turns. Cillian Murphy is great as Oppenheimer and Robert Downey Jr. is actually very good too, as Admiral Lewis Strauss.

Anton: You are right that Nolan’s previous movies are not so consumed by a single central performance, even if many of them have strong lead performances (I’m thinking especially of Matthew McConaughey in Interstellar or Guy Pearce in Memento). But here, like the best biopics, the lead carries the film and the day.

You are also right about the supporting turns too. The whole cast is excellent.

Anders: I turned to my friend at the end of the film and said, “Wild how Robert Downey Jr. is transforming into Jeremy Irons.” It’s his physical look, the gaunt face and glasses, but also the way he’s returning to material a bit less reliant on his ironic and detached Iron Man/Tony Stark persona, which transferred to a lot of his roles over the last two decades, even if I enjoyed them.

Aren: I’m struck by your comment, Anders, that Downey Jr. is essentially playing Jeremy Irons here. It captures part of how Downey Jr. is so good, as I hold Jeremy Irons to be one of the best performers ever (and having delivered the best ever performance(s) in a single movie). That coiling tension, the way that there’s contempt hiding beneath the civilized veneer, the way that Downey Jr. holds his head and speaks up from his chin to his eyes, almost, recalls Irons so deeply. The agitation of the performance builds. In all his work as Iron Man over the years, we’ve forgotten that Downey Jr. is mostly a cerebral performer, who’s all about using wit and wordplay and timing to deliver his performances. Package those traits in a character like Strauss and you get a mighty compelling foil for the protagonist.

Anders: I think it’s Downey Jr.’s best film in years. It makes me think that the potential of performances from early in his career was justified.

Aren: It’s true. The prestige actor that was teased in Chaplin and other films of that type. While Academy tastes have certainly changed over the past decade, this might be the film to get these dudes their Oscars.

Anton: And it’s a biopic! That’s Oscar gold, man. (Thankfully Nolan didn’t title the movie Julius.)

Anders: There's also a touch of Peter O'Toole in Cillian Murphy’s Oppenheimer, with his piercing blue eyes and enigmatic stare. It helps that Oppenheimer is a kind of T.E. Lawrence figure as well, both a leader who is successful in marshalling forces to win the war, but also feeling betrayed and ambivalent about the results of his quest. I think that given Nolan has expressed his love of Lawrence of Arabia, that is really the kind of historical epic that Oppenheimer is.

Anton: I would even go further with the connections to Lawrence. They are also both manipulative and great at building their own image, which they use to forward their missions. There is a modern antihero edge to both films and their central figures, which at the same time are larger-than-life personalities with immense achievements.

Aren: The movie is a biopic at heart, even though that doesn’t stop it from being several other things. But I think in a rush to note all the ways that Nolan is playing with timelines and perspectives and cinematic conventions, we can sometimes lose sight of the fact that this is his first biopic, his first adaptation of historical material (Dunkirk is also based on history, but it’s not an adaptation of a specific book about World War II), and his first pure prestige picture. The fit between director and subject matter is perfect, so I’m not going to accuse Nolan of chasing Oscar, but there’s a definite aura of prestige around this film and the marketing that was not there in previous Nolan films.

Anton: I think the prestige pitch was there for Dunkirk too, but there’s something different about this film’s presentation of history; Oppenheimer so much more of a narrative and historical account, whereas Dunkirk is like an experiential presentation of a specific historical event, limited in time.

Oppenheimer’s Parade of Dudes

Anton: Like the best and biggest historical epics, Oppenheimer takes the time to have an immense cast with perhaps 50 speaking and named roles, many of them famous historical figures, like Albert Einstein or President Harry S. Truman.

Aren: How many famous actors show up for a moment here or there? The cast is absurd. I could spend a whole paragraph here describing what a bounty of performances this film is, but I won’t. Instead, I’ll simply say that my friend who saw it with me in IMAX couldn’t help himself from leaning over every 15 minutes or so and declaring incredulously, “Is that who I think it is?” Only for me to say, “Yup,” every single time. That he can get Gary Oldman or Casey Affleck for a single scene speaks volumes to Nolan’s pull within the industry. Of all the supporting turns, who were your favourite dudes to show up?

Anders: I found Affleck’s Col. Pash terrifying. But I got a kick out of Benny Safdie’s Edward Teller. The image of him with the sunblock all over his face at the atomic test is already memorable. Of course, Kenneth Branagh as Niels Bohr is one of the big cameo moments, and he’s great. And, at first when I saw him in the film, I questioned the inclusion of Rami Malek, since he’s been a bit overrated lately, in my opinion. But David Hill becomes one of the film’s secret heroes. He’s very good in the senate scenes.

Anton: The casting works smartly, because I was going to write off the character but he surprises with his spine.

I thought Josh Hartnett was a welcome surprise.

Anders: I think it also provides a couple of key female performances, something that isn’t always present in Nolan’s very male-dominated worlds—though that’s not entirely true, given recent turns by Anne Hathaway, Jessica Chastain, and Elizabeth Debecki in his films. Nonetheless, I think that Emily Blunt and Florence Pugh, as the twin romantic passions of Oppenheimer, are key here as well. I think Blunt has the harder role, as her performance is less automatically sympathetic to modern audiences, and Pugh’s tragic turn earns some of the film’s most devastating moments. But both give nuanced, mature performances about relationships and lives that aren’t reducible to single elements.

Anton: Yes, I think both those performances, and the others you note, show that Nolan hardly has blinders on when it comes to female characters. He certainly builds time, space, and depth to both Blunt’s wife and Pugh’s mistress; both those roles could easily have been reduced to just the functional element of wife and mistress in a biopic. Instead, they get moments to tell their own stories, albeit in small portions. This is one way the film’s length is a strength.

Aren: Just a thought about Blunt’s performance as Kitty Oppenheimer: the film initially paints a portrait of her as the typical long-suffering wife to the troubled, brilliant protagonist, which is a biopic convention. There’s the scene where she’s so drunk and exhausted from taking care of their firstborn son that Oppenheimer has to drop off the kid with his friend, Chevalier. Or the knowing look on the face of Oppenheimer’s lawyer when he sees the flask in her purse during the security clearance appeal. Nolan is setting up the convention that she’s someone who is breaking under the pressure of being attached to this brilliant man who refuses to give her the attention and affection that she requires.

But then Nolan upsets our assumption. Think about the scene where Oppenheimer’s lawyer asks him whether he really wants Kitty to testify before the board, and Oppenheimer gives him a great response, which I’m paraphrasing since I don’t have the script available: “Only two kinds of people assume they know the truths of other people’s lives, children and fools, and you are neither. Kitty and I are adults.” And then following this line, we see Kitty testifying and initially we’re worried that the prosecutor, played by Jason Clarke, is going to rip into her unclear answers and really expose her as a fool. But the scene flips and Kitty makes him look like a fool with his bad phrasing and repetitive questions: “That isn’t phrased properly. I don’t like your phrasing.” Blunt is great here, with a little smirk, a little laugh in her voice, the warble of her voice that might betray nervousness transforming into a kind of chuckle.

Anton: I will note that my wife immediately pointed to that very scene as a good example of the nuance given to Blunt’s character, and how Nolan plays on our genre assumptions for a nice mid-scene twist.

Aren: The scene is also instructive as the entire film is framed through these twin hearings, which are really interrogations, almost trials, and the film itself is a kind of trial of Oppenheimer as a man. We are questioning who these people are and what they’re guilty of and then having our assumptions upset as Nolan lays out more evidence. And this is the case with supporting characters like Kitty and Strauss as well. We start to see the fullness of them as people as the film reveals more and more of their inner lives—as Nolan plays his hand, so to speak.

Anton: That’s a great analysis. So in Oppenheimer, Nolan’s use of twists is less about plot and more about character. Different facets of characters are revealed more than a big twist in the narrative.

Oppenheimer’s Twin Narratives: Fusion and Fission

Aren: Speaking of the narrative approach, we should focus on the twin threads focusing on Oppenheimer and Strauss: “Fusion,” which is in black and white and follows the perspective of Lewis Strauss during his 1959 confirmation hearing for a cabinet position, and “Fission,” which is framed by Oppenheimer’s appeal of his security clearance being denied in 1954.

Anton: OK, so after my single viewing, I thought that the two investigations would be considered one thread, and the chronological progression forwards might be the other, but would you say that each investigation defines its own storyline with its own related flashbacks? I think I didn’t nail down the narrative structure entirely correctly in my review, working just from memory off a single viewing.

Aren: It’s tricky, because there’s not a clear break between the two. They are the binary threads of the narrative, both telling the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer, yes, but from very different perspectives and with different timelines, of a sort, since they both have their own flashbacks and versions of the same events.

Both are trials, but technically hearings, as characters in both threads are careful to explain. The verdict in both accounts doesn’t have a legal bearing in a criminal sense, so they don’t have to have the burden of evidence in coming to their conclusions on the two men. One is about Oppenheimer’s security clearance. One is about Strauss’s confirmation to Eisenhower’s cabinet as Secretary of Commerce. One is tied to Oppenheimer’s exhortation at the beginning of his security clearance hearing that his actions with the Atomic Energy Commission can only be taken in light of his entire life. The other is tied to Strauss’s thoughts about himself and Oppenheimer, and his version of his career, which he thinks has been categorically undermined by Oppenheimer.

We get alternate versions of the same scenes in both threads. For instance, we famously see the encounter between Oppenheimer, Einstein, and Strauss from both perspectives. We also see different versions of the 1949 meeting and argument over the development of the hydrogen bomb, and the hearing where Oppenheimer publicly humiliated Strauss over his opposition to exporting isotopes to Norway. There is a Rashomon effect going on here, but we’re not meant to believe that Strauss’s version of these events is as true as Oppenheimer’s. Rather, they demonstrate what kind of person Strauss is by letting him paint a heroic portrait of himself and a villainous portrait of Oppenheimer.

Anton: Great. This is helpful.

Aren: Essentially, the two threads of the film represent the two parts of a nucleus that are produced during atomic detonation. Fission is about breaking the nucleus apart into lighter nuclei, which then unleashes a devastating force. Fusion is about joining these nuclei together, which is more powerful and more devastating. Fission is how atomic bombs such as the “Little Boy” and “Fat Man” bombs that were dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki operate. Fusion is how a hydrogen bomb, developed by Edward Teller, also known as a thermonuclear bomb or “Super,” works.

So the film is two threads and Nolan interweaves between them and then ultimately joins them at the end, as if breaking and then fusing an atom. I’ll let you two speak more to the cinematic work at play here, since I’ve gone on long enough, but I also want to mention that the interplay between the threads reminded me of Amadeus. Oppenheimer is Mozart and Strauss is Salieri. I’m not sure it’s a direct reference for Nolan, but the historical lens and the way that Strauss’s bitterness fuels so much of the film’s perspective makes it seem like Amadeus might be one of the best comparisons for the film.

Anders: Yes. Strauss is a Salieri.

Anton: Good point about Amadeus. I hadn’t thought about that. It’s funny, because Amadeus might be one of the only other three-hour biopics that I’ve watched that is as entertaining and quickly paced. Such a great movie.

I feel like I didn’t quite follow the first exchange between Oppenheimer and Strauss very well, about their backgrounds. There’s clearly some class conflict there.

Aren: Do you mean moments like Strauss’s early comment about being a self-made man and selling shoes instead of being a physicist? The implication here is that Oppenheimer came from wealth, which was true. He could afford to study and go around Europe learning about theories, which Strauss was interested in himself, but couldn’t afford to do. So when Oppenheimer calls him just a “lowly shoe salesman,” Strauss has to correct him: “Just a shoe salesman.” Strauss thinks he’s being condescended to. And then Strauss uses Oppenheimer’s version of that line later in the film to describe himself and his metaphorical crucifixion before the public, which is acting on behalf of Oppenheimer. The film weaves a dense portrait of these men, and a second viewing definitely helps understand it better.

Anton: Yup. For sure. And, if I remember correctly, Salieri has a more humble origin in Amadeus, whereas Mozart comes from a more respectable family.

Anders: There’s an interesting aspect also about class and ethnicity here, of Oppenheimer’s communist sympathies and the origins of his family as European Jews, versus the very Germanic “Strauss.” Though, note, “It’s pronounced Strass.” The embracing or distancing of oneself from origins, whether ethnic or political, is a key theme. This is also echoed in the larger narratives around scientific discovery.

Aren: Strauss is also Jewish, remember, but less obviously so. And despite being born poor, he’s richer than Oppenheimer by the time they meet. The film examines the mythmaking of both these men.

Anton: And the self-mythmaking.

Oppenheimer’s Stylistic Approach

Anders: It’s worth spending some time discussing the film’s formal approach and stylistic hallmarks of Nolan’s work. Interestingly, this might be in some ways one of Nolan’s most experimental works, at least on the level of abstract or non-traditional imagery, though he did move into that kind of material in Interstellar as well. However, this approach is also reminiscent of David Lynch’s exploration of the moral and spiritual impact of the atomic bomb on the American soul in Twin Peaks: The Return. The highly experimental central episode, “Episode 8,” which is also centred on the Trinity test, has lots of experimental photography, attempting to capture the way that destructive force of the bomb is manifested from a microcosmic level.

But in many ways Oppenheimer is stylistically of a piece with Nolan’s earlier films, though I would say along with Dunkirk, it might be his most radical for using such notions in a non-science fiction context. (Though the truth is that the atom bomb is the moment that science fiction and science fact start to blur in our world.)

Aren: If you’ve watched Twin Peaks: The Return, it’s impossible not to think about “Episode 8” and its demonic vision of the Trinity test. Nolan’s film is not radical on the level of Lynch’s work, but it does take a dense, assaultive approach to the material, which assumes that you are going to pick on threads early in the film and remember their importance hours later. There are lots of characters, but also lots of concepts, historical tensions, political tensions, procedural elements to keep in mind. I’ve heard from people at work who’ve mentioned they wish the film spent more time explaining how nuclear fission and fusion work, and the actual mechanics of the bomb.

Anton: Yes, I’ve heard that complaint from people who are gearheads and highly technical people, very into the mechanics of things. I think it’s a fair expectation, given this was sold as a movie about making the atomic bomb.

The film is more interested in the human and philosophical side of things, or as Oppenheimer would call it: theory.

Anders: From what I’ve seen on some Letterboxd reviews, many clearly didn’t get it. I wrote on Letterboxd after Tenet something that might as well apply to Oppenheimer:

You don’t have to like Christopher Nolan the way I do, but let’s just get something out of the way as people call each other “dumb” for not getting it or this movie “dumb” in its grand ambition: it's not a matter of anyone or anything being dumb. Either you’re interested in the same ideas Nolan is or you’re not…

Now, I might modify my statement for Oppenheimer in that I don’t think the subject matter is simply a case of esoteric “interest” in abstract concepts like “time,” but rather a subject of incredible moral and historical importance. So, I’ll say, you’re not dumb for not liking the film, but I might accuse you of being incurious.

Aren: Yeah, for sure, but people are incredibly incurious these days. They want the characters and situations depicted on film to align perfectly with their own, and if they’re asked to explore a different time and place and mindset for several hours, they get frustrated.

Anton: I certainly agree that it is fair for some to dislike Nolan for his thematic and stylistic preoccupations. Much of that is a matter of taste. I also think that Nolan demands a lot from his viewer. But not too much. He’s not truly avant garde, and always provides redundancies for clarity. But he wants to push his mainstream audience, which I actually think is one of his selling points, in a way. It’s partly, it would seem, why he was selling this three-hour biopic during sports broadcasts. He invites regular people to his latest movie, which, as “a Christopher Nolan film,” is sold as an event in itself and not because of any franchise associations. Most importantly, he never asks his mainstream audience to turn off their minds, or their hearts for that matter. I think this is why so many who say yes to his films come away from them almost super-charged and excited by the mental labour they had to put in to enjoy them.

Aren: He’s also playing with some of his classic directorial trademarks in Oppenheimer, which are a part of the fun for audiences. He builds in the repetition of scenes and reiterations of key lines so people follow what’s going on, but much of the fun of a Nolan film is keeping pace with its narrative. In Oppenheimer, there’s the divergent timeline, which jumps around, which recalls not only Dunkirk, but also more specifically Memento in its use of black and white vs. colour to differentiate the two threads of the film. There’s the overwhelming use of music to underline the emotional aspects in most scenes, which is made all the more noticeable by its absence in the two most impactful moments in the film: the Trinity test and Oppenheimer’s speech at Los Alamos after Hiroshima. It’s Nolan using all his tricks, to make the film challenging, but also accessible to general audiences.

However, I will note that many people don’t understand montage these days, and Oppenheimer has a radical use of montage. Honestly, the first 30 minutes are basically a mini Terrence Malick movie, racing through Oppenheimer’s past in Europe, flitting us from one classroom to another to meet one brilliant physicist after another. And we get the experimental flourishes of waves and water droplets and particles in the night and the sky. It reminded me of Malick’s A Hidden Life because of the time period and the retrospective view, where we’re clearly seeing someone’s memories.

Anders: Even a bit of Voyage of Time.

Anton: Good point. Malick and Nolan are the Anglosphere’s biggest montage filmmakers. It’s a different approach than what dominates the indie and prestige tiers these days.

Aren: I actually wish we had seen more of the waves colliding, those awesome little visions of quantum reality. They’re the kind of depictions that make physics so exciting and strange. There’s that great first moment when Oppenheimer first starts teaching and he only has one pupil. He describes the contradictory nature of physics in the 20th century: “We’re both waves and particles. That’s not possible, but the math shows it’s true.” I’m not sure whether our dad has seen this movie or not, but I can imagine him fawning over such a line and the film’s curious exploration of “the quantum world,” as he always likes to mention.

Anton: Like Interstellar, many moments in this film are sublime, tapping into the simultaneous fear and attraction that undergird our feelings about the deep nature of the universe.

OPpenheimer As Triumph, As Tragedy

Anton: We’ve talked about the characters and narrative and other features, but let’s conclude by assessing the impact of the film’s themes. What is it saying? What did it make you feel? You’ve both already hinted at the film’s impact on you.

Aren: After my second viewing, Oppenheimer most reminds me of Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises, which is perhaps most fitting, as that film takes the Japanese perspective of World War II, while this one takes the American perspective. Both films are unconventional biopics, movies about World War II that don’t have any battle scenes, and most importantly, about brilliant men, almost brilliant artists, whose talents created destruction. Both films are about the way these men’s legacy is destruction and death, despite the obvious love they have for their field and the possibilities of their work. They are moral investigations, but also celebrations of the central figures. They both have fanciful, almost fantastic sequences, that take us into the minds of the central figures. In The Wind Rises, we see Jiro Hirokoshi’s dreams about meeting the famous Italian plane designer Caproni, which recur throughout the film. In Oppenheimer, we see Oppenheimer’s visions of hellfire and his fantastical understanding of quantum mechanics and theoretical physics through impressionistic visions of waves, particles, vibrations, all coming to mind from simple acts like rain drops on a pond or broken glass on the floor. What do you guys think of the comparison?

Anders: I think The Wind Rises is a great comparison, in that it's also about having one’s passion and art, if we can call engineering and physics art, turned to war. There’s almost a naivete about both men in thinking that a plane or a bomb, sorry, “the gadget,” wouldn’t be used to such ends.

Anton: Yes, good comparison. Both men are making machines for war and thinking they are not, which is obviously blind in a way, but on another level raises the whole question of what is human invention? After all, almost every tool is also a weapon, every invention to save space or time also costs something in another way. The film asks whether theory can ever just be theory, and I would say that the film posits that we have an inquiring and creative nature that wants to pursue ideas and invention regardless or without heed to the consequences or what comes next. All the big inventions also spark larger “revolutions,” to borrow the language of the film, which situates the atomic bomb as the ultimate manifestation of the remaking of the world under modernity.

I think one reason the movie is so haunting is that it is asking fundamental questions about what we are doing, on the scale of collective humanity and not just as nations or societies or as individuals. What are we all doing? Which is why the film also speaks to our moment, with AI and other things. Oppenheimer gets at deep, troubling concerns in the back of our minds.

Aren: There are many moments in Oppenheimer that stunned me. The Trinity test and Oppenheimer’s speech are the obvious ones. But no moment affected me quite like the ending, where we finally get to hear what Einstein and Oppenheimer said to each other. It goes like this:

Oppenheimer: When I came to you with those calculations, we thought we might start a chain reaction that might destroy the entire world.

Einstein: I remember it well. What of it?

Oppenheimer: I believe we did.

Horrifying stuff, just bone chilling! It’s a very similar ending to Inception or Dunkirk or Interstellar where the montage clarifies around one key moment, but the meaning of this film is much more dire than those ones. Dunkirk carries the promise of future hope in its final moments, with Winston Churchill’s speech and the hero’s welcome for the soldiers. This film seems certain we’re doomed.

Anders: Yeah. It’s definitely a weighty ending that leans towards pessimism. But, it’s also about uncertainty. And our inability to justify ourselves. When we finally get the reveal of the Oppenheimer and Einstein conversation, it is a bit of resolution of the uncertainty principle. The wave function collapses and we finally have an answer, but it also ripples backwards through the film and taints everything Oppenheimer did. Very powerful.

Anton: But what is the starting point of that chain reaction? The opening title mentioning Prometheus makes this a fundamental human trait. We are on a twin path of invention and destruction. From Prometheus stealing and giving us the gods' fire. From Eve stealing the apple to gain knowledge, or the first murderer, Cain, being the father of technology and cities.

Aren: Nolan is tapping into some core truths about human, mythic truths. This being the final scene, and then us getting visions of nuclear missiles and a hellfire consuming the atmosphere, it leaves you with this heavy weight.

Anders: Absolutely. Here is where I'd also emphasize the notion of "uncertainty” one more time. This is the key thing which unifies the scientific and human elements of Nolan’s interests, much as he did with Interstellar, which I think is the other key Nolan film this reminds of at moments. Quantum physics leads to a revolution of causality and certainty. Likewise, modernity and the world wars do the same. As Oppenheimer notes in his dive into art, politics, poetry, once you see the revolution in one area, you start to see it all over.

Calum Marsh posted this quote from Cormac McCarthy’s Stella Maris as his Letterboxd review that serves as a nice encapsulation of the moral and cosmic significance of the film’s subject matter:

That there was an ill-contained horror beneath the surface of the world and there always had been. That at the core of reality lies a deep and eternal demonium. All religions understand this. And it wasn't going away. And that to imagine that the grim eruptions of this century were in any way either singular or exhaustive was simply a folly.

Heavy stuff. Haha

Anton: There’s something Lovecraftian about that quote too. And yes, the uncertainty is there in all his works. It’s the spinning top at the end of Inception.

Aren: Oh yes. That quote fits with my idea that the bomb is actually a deeply demonic invention, one which gets to the core of reality, but perverts it. It taps into the fundamental atomic essence of our universe, but uses it for destruction, transforming the life-giving energy of the sun into a hellfire. It’s why the Prometheus comments are so great off the top, as fire is creative and destructive, a gift and a curse of the gods, associated with heaven, yes, but more so hell. It also makes me annoyed with people who don’t like the tone of the material. Such a flippancy in response to a film like Oppenheimer reveals a deep incuriosity and unseriousness in people.

Anders: I am very disappointed in people who think that digging into what I see as very fundamental and deep areas of reality is unimportant, because it’s not about “relevant” topics like race and gender. I think there’s a sense among some audiences and critics that those are more worthy concepts to think about, morality and society, and that Oppenheimer or physics is cold or inhuman.

But I think it simply reflects our silly and shallow society.

Anton: We are “a little people, a silly people,” à la Lawrence of Arabia (which are the types who ejected that film from the Sight and Sound list, I will add.)

Anders: The film boldly connects science and technology to a fundamental morality of the universe, and this is reflected in the uncertainty principle once again. We can’t always know if what we’re doing is “right.” It may be that history judges us as wrong, something I think is often overlooked in contemporary discussions of social mores. What will we be judged by in the future? But we have to act, or the “wave function” of our lives will remain indeterminate. We can’t sit on the fence.

Aren: At least most audiences are responding to it. People were rapt watching it both times I went. One person in my row was leaning forward the whole time to take it in in that really intense way. I think it’s a movie people feel in their bones, they know the bomb is not normal, that it’s bigger than most stories we tell.

Anders: Definitely a lot of passion when people actually experience it. One guy shouted out at the screening I went to. I do think normal people are reacting in ways that demonstrate this. But the online set seems to want to diminish the film, finding this kind of emotional reaction—like the one that Bilge Ebiri describes in the earlier piece we started with—too much or embarrassing. If this and Interstellar don’t put the lie to Nolan as not being emotional, I don’t know what will.

Oppenheimer (USA/UK, 2023)

Written for the screen and directed by Christopher Nolan, based on the book, American Prometheus, by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin; starring Cillian Murphy, Emily Blunt, Matt Damon, Robert Downey Jr., Florence Pugh, Josh Hartnett, Casey Affleck, Rami Malek, Jason Clarke, Matthew Modine, and Kenneth Branagh.

Anders and Anton discuss their appreciation of the third season of The Bear and the mixed critical reception to the latest season of the hit show.