Why You Should Revisit the Tron Movies in 2023

I’m sure you already have an expectation of my main reason to revisit the original cult classic, Tron (1982), and its 21st-century sequel, Tron: Legacy (2010).

AI, of course. Although the rumblings began in late 2022, January 2023 saw generative artificial intelligence, such as ChatGPT, propelled to the centre of our news, culture, and social media. While some of the panic and elation have subsided, it seems clear that AI will continue to impact and reshape our work, education, and cultural production going forward (or at least until a Butlerian Jihad, à la Dune, is enacted).

But AI isn’t actually the main focus of the Tron movies. Yes, there is ENCOM’s Master Control Program in the original film, which evolves into a malicious, domineering virtual intelligence that mirrors our worst nightmares about an AI chatbot unleashed on the Internet. In the original Tron, the MCP, unbeknownst to its makers, gathers more and more programs under its control. The MCP is like a milder version of the genocidal Skynet of The Terminator movies: both are AI villains that stand as fictional prophecies about the dangers of unleashing technologies that can exceed human capabilities and control. At the same time, both the MCP and Skynet are classic techno-tyrants, like so many in science fiction, whether virtual or otherwise. All that said, this piece isn’t going to be simply an unpacking of the Tron films’ treatment of AI.

Rather, I recommend revisiting the Tron movies for two reasons. First, I think they are both formal wonders telling inventive adventure stories. They are fun, have some neat ideas, and are worth checking out if you’ve never seen them before. Second, both films actually go deeper in their portrayals and critiques of tech than only their representations of villainous AI.

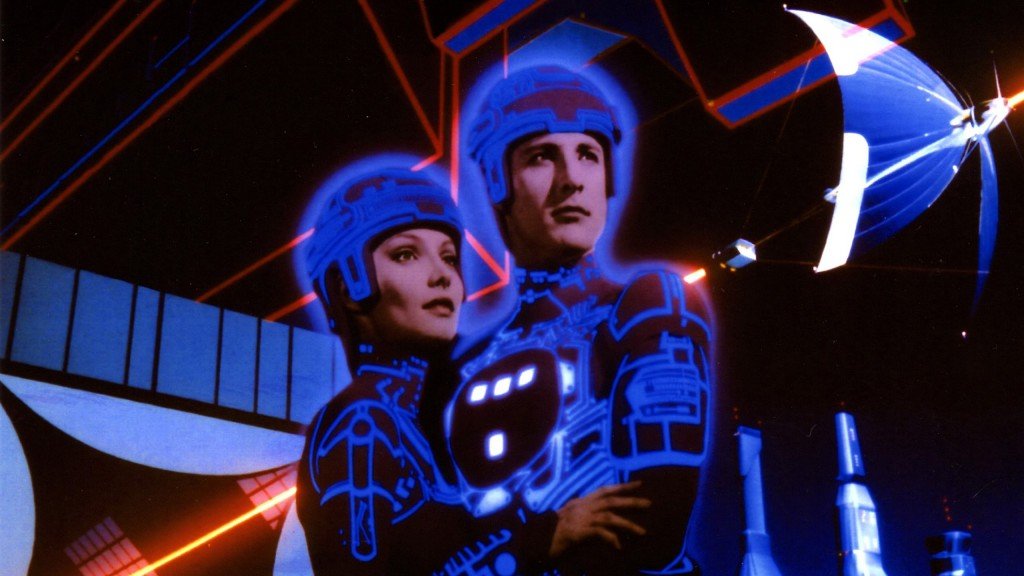

Tron Is a Visual Landmark for Geek Culture

The original Tron is cinema’s epitome of computer geek culture, both in its artistic production and in its representations. Not only is Tron considered the first feature film to utilize 3D computer generated animation, but the film itself is about the tech industry. Set somewhere vaguely on the West Coast, probably Seattle, the film depicts ENCOM, a tech company that makes video games while also conducting advanced research into computing and other scientific endeavours. The film’s adventure in the computer world is premised on the fact that ENCOM scientists have developed a laser that can transform matter and transport it into the digital world, which, naturally enough, is visualized as a world with human-like programs that move around and do their jobs.

The first time I watched Tron (which was actually in 2010), I thought the computer world looked great but was a bit hokey. I also found the quest adventure clichéd and the film’s portrayal of the tech industry kind of silly. For example, I was unconvinced by how the new VP rose to prominence because he stole the video game that Flynn, the main character, created. (Flynn is played with gusto by a young Jeff Bridges, and David Warner plays the villainous exec, Dillanger.)

Today, the portrayal of ENCOM still looks exaggerated, yet it’s also strangely on point. It captures what we call “the tech world” in a few broad strokes, conflating the development of video games, computer software, and experimental science. Nowadays, the big tech multinationals like Apple and Microsoft and Alphabet (Google) have their hands in all sorts of things, from entertainment to hardware to experiments in generative AI to mapping and hacking human genetics. With Flynn, the master programmer who also runs an arcade, we also get the extended adolescence that seems to characterize many titans of tech, whether it’s Elon Musk or Mark Zuckerberg.

As the themes of Tron are pronounced and simplified, so too are the visuals bold, striking, and minimalist. The visual representation of the virtual world is unique, like nothing else I’ve seen on film. A world of clean lines and tinted greys, with streaks of colour highlighting characters and objects, suggesting the look of old computer screens, which featured white or green pixels and blocky text against black. Looking back, I’m genuinely surprised that Disney, in the post-Walt era, spent so much money on an experimental film. In this sense, Tron is a successor to Fantasia, an example not of Disney’s greatest narratives but rather their greatest visual accomplishments

While viewers today might complain that the digital world in Tron seems like a computer version of Disney’s later film, Zootopia (2016), with programs instead of animals standing in for different human types, on a deeper level it reveals the human tendency to impose human patterns on technology, which we see prominently in current AI discourse. At the end of the day, most of us think of the virtual world, the world behind our laptop and smartphone screens, as a “world.” Tron is not only the urtext for such representations of the digital world in film and television, influencing later Disney movies like Wreck-It Ralph (2012), but the movie also makes literal what we metaphorically talk about when we talk about this extra layer of reality, cyberspace. It’s a concrete representation of abstract concepts. To its credit, Tron embedded this way of representing the digital world in pop culture.

On this viewing, I noticed further eccentricities in the film’s thematic concerns. There’s an uncommon religious element that pervades the narrative. For instance, many of the virtual-world programs are played by the actor who plays the corresponding programmer in the real world. So, Bruce Boxleitner, who plays the human Alan Bradley, also plays Tron, a security program developed by Bradley. Jeff Bridges also plays Flynn’s hacking program, Clu (which stands for Codified Likeness Utility). Thus, the film suggests that the pattern of imago dei (humanity being made in “the image of God”) repeats lower down the ladder in the form of human sub-creation in the digital world. The bad guys in the digital world keep labelling the good programs as “religious fanatics” who believe in the “Users,” which is to say, human creators and operators.

In spite of its many striking elements, Tron is not a great movie. Its narrative is too poorly paced, sometimes slowing to an arduous pace that recalls Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979). Both films suggest productions that felt they couldn’t cut any of the visual effects they had spent so much time and money on.

Nevertheless, writer-director Steven Lisberger deserves immense credit for Tron, which, in 2023, is firmly a landmark in cinema. Tron set patterns for the visualization and understanding of computers that continue to this day. It is a cult classic that earns its status.

Tron: Legacy Sets the Template for Legacy Sequels

Is Tron: Legacy the first legacy sequel? It precedes Jurassic World and The Force Awakens by half a decade, as they came out in June and December 2015, respectively. Although J.J. Abrams’ Star Trek came a year before, in 2009, Star Trek is more precisely a remake in addition to being a reboot, as it recasts the original crew of the Enterprise while diegetically stitching its new continuity onto the old storylines through a cosmic event. Tron: Legacy fits the pattern of legacy sequels perfectly, being emblematic of many of the genre’s concerns, such as generational conflict, which sometimes serves as metacommentary on the franchise’s different phases. Here the conflict is between Flynn and his son, Sam (Garrett Hedlund). Early in Tron: Legacy, the audience is reminded of the first film through Flynn’s conversation with his son as a child at bedtime. The scene features merchandise for Flynn’s Tron video game, including the real poster for the original movie, thus conflating the memories of characters with that of audience members.

The audience is invited back into the world of Tron through these flashback scenes before catching up with Flynn’s son Sam in the present day. Presaging Luke Skywalker’s absence in The Force Awakens, Flynn has gone missing at the beginning of Tron: Legacy. As with both Jurassic World and The Force Awakens, the storyline in Tron: Legacy parallels many of the narrative structures of the original film, including, for example, another arena light cycle race. At the same time, everything is “bigger, louder, [with] more teeth,” as Bryce Dallas Howard’s Claire in Jurassic World describes the new dinosaurs in a line that has come to characterize the whole legacy sequel program.

The story in Tron: Legacy has more action and more spectacle. The soundtrack is louder, both the sound editing and the propulsive, incredible soundtrack by Daft Punk, which moves between atmospheric background tones and beat-heavy dance—or in this case, action—music. Akin to John Williams’ music for the Star Wars films, Daft Punk’s music is essential to the effectiveness of virtually every scene in the movie. The score is also one aspect that is a huge upgrade from the original film.

The performances also have more bite. Garrett Hedlund is more rough around the edges than Flynn, who is usually more genial in the original film. Sam, who owns the majority shares of ENCOM but has largely checked out and instead pulls extreme sports pranks, even anticipates some of the strange personal cycles that characterize the tech industry, which seems more dominated by personalities than other industries. We get a few wild performances, such as Michael Sheen pretending to be David Bowie going crazy during a bar fight. And Jeff Bridges not only returns to the role of Flynn, but also brings with him the elder statesmen status he acquired through his memorable performances over the years as well as his Oscar win in 2010. Most notably, Bridges brings aspects of the Dude from The Big Lebowski to this older, Obi-Wan Kenobi-like version of Flynn.

Sharing the meta-concerns of all legacy sequels, Tron: Legacy even makes its representation of the digital world an explicit theme in Flynn’s opening monologue:

The Grid. A digital frontier. I tried to picture clusters of information as they moved through the computer. What do they look like? Ships? Motorcycles? Were the circuits like freeways? I kept dreaming of a world I thought I'd never see…. And then one day, I got in.

The opening scene shows the digital grid lines giving way to the streets of a real city, forging a direct representational link between the worlds, rather than just emphasizing their visual contrasts. In our increasingly digitized present, the lines between the virtual and the real are no longer so clear-cut.

The movie’s visual effects are stunning, that is, apart from the poor CGI de-aging of Jeff Bridges (which I complained about in one of the first reviews ever posted to 3 Brothers Film). As far as I can tell, this is the first instance of this technique (Captain America would show Chris Evans as skinny the next summer). The de-aging here, however, takes on a strange self-reflexivity with the character of Clu, who is a digital copy of Flynn (recall that Bridges played both Flynn and Clu in the original). While the de-aging is functional for Clu, it does not work during the flashback scenes depicting a young Flynn. Unfortunately, the de-aging tarnishes the otherwise impeccable visuals of the movie.

The minimalism of the original film still dominates the aesthetic of Tron: Legacy, with the universe in the computer visualized mostly in shades of black and grey, with edges and lines of striking white or red. But the costumes and the overall effect of the design are more stylish and less dorky here, feeling like the difference between a boxy Apple computer from the 1980s and an iPhone.

The film is deeper than I complained in my 2011 review. Tron: Legacy continues to develop the religious themes of the original. In the first movie, Flynn created a program, Clu, in his own image, but Clu becomes a Luciferian figure in the sequel. More intriguingly, Tron: Legacy introduces new digital beings, the ISOs (or Isomorphic Algorithms), who mysteriously arise without Flynn’s or other human creation. Is the film suggesting spontaneous generation or a higher power’s intervention in the new digital world?

One visual image demonstrates the contribution of Tron: Legacy to current conversations about the nature and value of tech. In an expositional scene that intervenes between the 1980s opening and the rest of the film, we see a young Flynn on a television shouting about the glorious new future he is building:

In there is a new world. In there is our future. In there is our destiny.

Later in the film, we see Clu in front of an assembled army of programs, who are about to break into the real world, throwing a fascistic rally glorifying their coming conquest. The visual parallel underscores the central themes in regards to both Flynn and his artificial double. Flynn’s quest for perfection was flawed from its premise, since perfection is beyond human understanding and capability. At the same time, Clu’s quest to make a perfect system will inevitably lead to totalitarian impulses. Clu shouts to his assembled army:

We have created a vast, complex system. We’ve maintained it; we’ve improved it. We’ve rid it of its imperfection. Not to mention, rid it of the false deity who sought to enslave us.

In the years between the events of the two films, Clu had launched a genocide of the ISOs and the Users, which has a distinctly anti-religious edge. The film starkly connects the utopian aspirations and marketing of tech with the dark ambitions of modernity, which seeks to update all things and make all things conform to its presumably more efficient system.

There’s also more to the father-son relationship than I first noticed. Now that I have kids, I think the film’s message about how the creative type’s pursuit of technical perfection can make him or her blind to the sufficiency of human beings around them is actually poignant, and more valuable than the generally bland family dynamics we’ve been presented with in blockbusters since 2010.

Tron: Legacy’s combination of sound and vision heralded Joseph Kosinski as a contemporary master of spectacle. Kosinski understands the beats of the blockbuster, which he even improved on with Top Gun: Maverick (2022). I noticed how early shots of Sam zooming on his motorbike along a freeway recall shots of Maverick on his bike. Fans of Maverick should go check out the director’s first film, which is definitely an achievement for a feature debut.

Tron (1982, USA)

Directed by Steven Lisberger; screenplay by Steven Lisberger; starring Jeff Bridges, Bruce Boxleitner, David Warner, Cindy Morgan, Barnard Hughes.

Tron: Legacy (2010, USA)

Directed by Joseph Kosinski; screenplay by Edward Kitsis and Adam Horowitz; starring Jeff Bridges, Garrett Hedlund, Olivia Wilde, Bruce Boxleitner, James Frain, Beau Garrett, and Michael Sheen.

Looking back on the career of a great Canadian comedic actress.