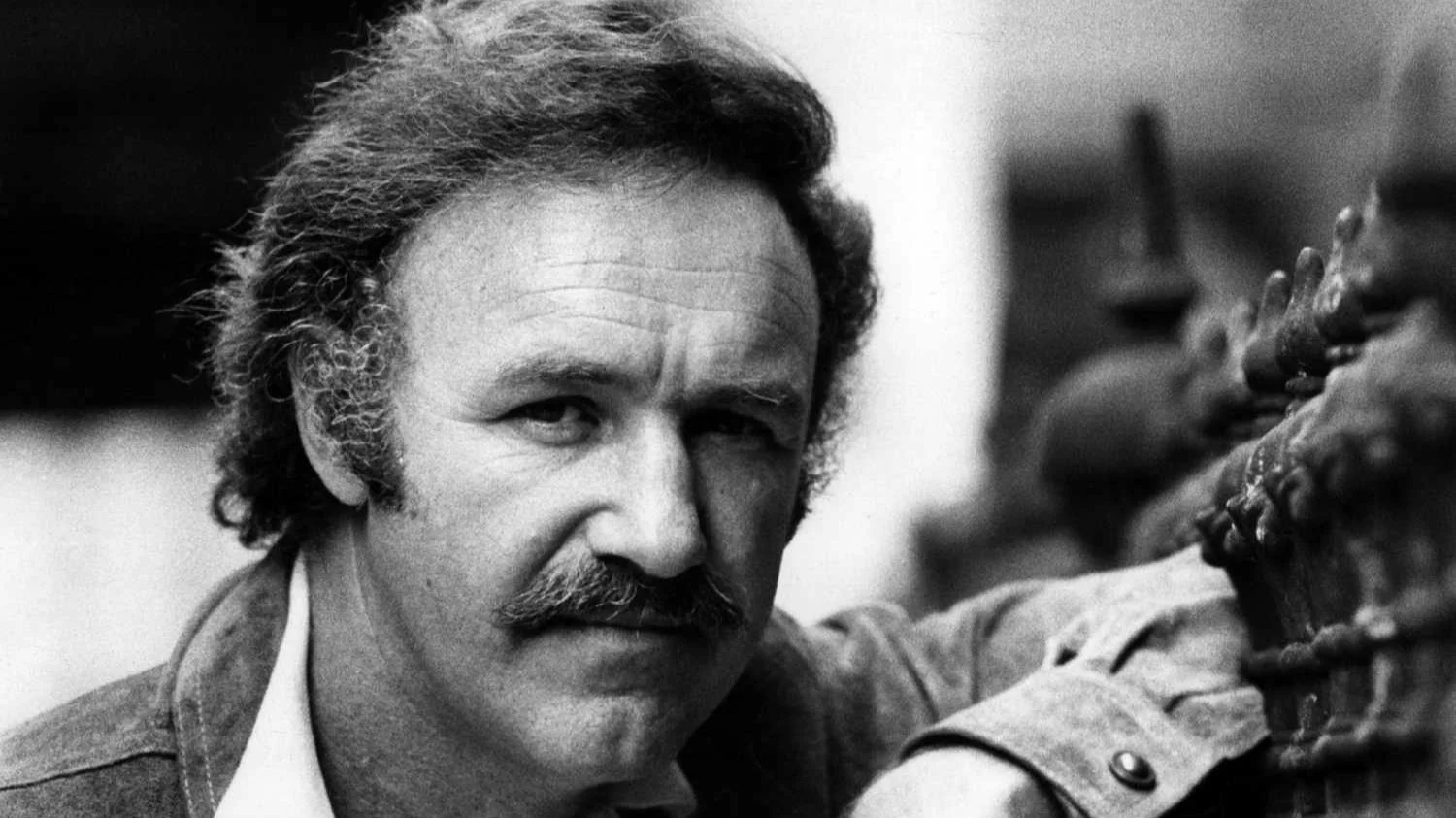

Remembering Gene Hackman (1930-2025)

Anton: Gene Hackman is one of the greats! From the late 1960s until the early 2000s, when he retired, Hackman starred in numerous films, many of which are classics and some of which rank among the best films of all time. But he’s also the kind of actor who rarely if ever gave a bad performance. I honestly cannot think of him being bad in a role, even if the movie itself is mediocre or bad. He never seemed to phone it in.

Aren: He was a pro because he didn’t look like a pro. Gene Hackman was already old when I was young and first watched his movies, so I never had that sense of discovering him or really feeling like he was an actor of my era. (Although, in retrospect, it’s funny because even when I went back and watched his earliest work, he didn’t seem young in them either.) But even then, I knew he was a good actor and his specific authenticity stood out to me. He had a gruff, no-nonsense approach to his roles, which made me think of him as a real person, even when I was a kid.

Anders: I will admit to this: I never appreciated Hackman enough when I was young. I think his normalcy put me off seeing him as great. Another part of it is that his best roles were in films I didn’t see until I was a bit older, but as I’ve aged I’ve come to appreciate his particular kind of leading man more. He’s gruff and prickly, but he’s also a bit relatable. I’m honestly not sure that today’s Hollywood could ever manifest someone quite like him.

The Superman Movies (1978–1987)

Anton: Before we get into a more chronological discussion, I want to ask you what is the first movie you can remember seeing Gene Hackman in? My guess is that it might be the same movie for all of us.

Aren: I think it was Enemy of the State, which I might have seen in theatres when I was seven.

Anton: Ha ha. Did you come with us to Enemy of the State in theatres? Wow.

I’m pretty sure I first encountered Gene Hackman through the original Superman (1978), and I would expect the same for a lot of people our generation. In my 2022 article “Ranking the Christopher Reeve Superman Movies,” I said that “I know others like Hackman’s Luther, but I’ve never really adored his hammy portrayal of the character, particularly his obsession with real estate.” Calling Hackman hammy might suggest I think he’s terrible in the role. But that’s not it for me. I don’t think he’s a great Lex Luther; he’s not what I envision for the character. But I do sort of enjoy his performance as its own thing, and I enjoy how much fun he is having in the role. And his performance is certainly very memorable. I can hear him speaking as Luther in my mind right now: “Superman!”

Anders: I think I had to have seen Superman first of all his films. Most of his other films I was aware of when I was a kid were hard-R New Hollywood films or his work with Clint Eastwood or Tony Scott in the 90s, which I hadn’t seen. So, Superman was definitely my first exposure to him. Which might account for why I wasn’t as high on him as a performer until later.

Aren: It’s been years since I’ve seen the Christopher Reeve Superman movies, so I barely remember Gene Hackman’s role as Lex Luthor. Most of what I recall is that I thought it was weird for him to play the role, but I think it was because I always associated Hackman with being a gruff old man and Lex Luthor as a very suave, sophisticated villain. So it was hard to blend the two in my mind, but that probably says more about casting than about Hackman’s actual work in the role.

Anton: I revisited all the films during the Covid years, and I still don’t understand why he was cast in the role. I suspect he was considered a bankable star in the 1970s, whereas Christopher Reeve was largely unknown?

Anders: Part of it is Hackman’s star power, post-French Connection. But remember also that Lex Luthor in the comics of the time, prior to John Byrne’s re-working of the character post-Crisis on Infinite Earths in The Man of Steel (1986), wasn’t necessarily a suave businessman or billionaire like he became later. He was a mad scientist, self-confident and sure of himself as a genius. I think Hackman’s supreme confidence that always manifests under his gruffness and straight talk works well in the role.

Anton: That’s a good reminder, Anders.

I’ll also add that I think Hackman is better when he is playing off of Zod and the other wooden evil Kryptonians in Superman II (1980). Hackman also returned for the fourth and last Superman movie, The Quest for Peace (1987), which is a famously bad movie. But Hackman is actually fine in the movie, clearly enjoying himself amongst some of the most ludicrous villains ever created for a superhero movie. Hackman’s performance in Superman IV is not worth seeking out though.

His Breakout: Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

Anton: Okay, let’s move back in time. My understanding is that Hackman actually got big relatively late in life for an actor. He was middle aged.

Anders: Yeah, he was 41 in 1971’s The French Connection, when he became a true star.

Anton: Hackman’s first significant role is something of an outlier role for him, in a movie that I recognize as significant but which I think is highly overrated (see my essay, “The Faded Realism of Bonnie and Clyde”).

Aren: Bonnie and Clyde is the movie that put Hackman on the map and got him hired for The French Connection. Is it weird to say that I think about his supporting performance as Clyde’s brother Buck in this more than I think about Warren Beatty’s or Faye Dunaway’s performances as the title characters? I like Bonnie and Clyde more than you, but it’s more notable for historic reasons than cinematic, in my mind. But also being our introduction to actors like Hackman means that, regardless of its worth as a film, it will always be a significant film historically.

Anton: I agree that Bonnie and Clyde are not the most interesting characters or performances in the movie.

Surveillance Thrillers of the 1970s

Anton: After Bonnie and Clyde, things took off for Hackman and he had a great decade—one of the best—in the 1970s. Not every good actor gets to be in more than one landmark canon movie, but Hackman appears in a number of them.

At some point, most every budding cinephile turns to the 1970s American New Hollywood, and Hackman holds the lead role in two stone-cold classics: William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971) and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974). Both films are thrillers centered on surveilling people.

Aren, you were commenting the other day that Friedkin’s style can be so rough at times. In the case of The French Connection, it makes Hackman, who was never the fashionable leading man, perfect for the aesthetic. Hackman looks like a real man doing real work in these two roles.

Aren: Yes, exactly! Hackman is always authentic. He looked like a real guy. He acted like a real guy. It’s why his work as Popeye Doyle is so great, especially as Popeye is a magnificent bastard, a complete asshole to everyone around him.

I rewatched The French Connection twice in the wake of Hackman’s death, and both times, I was struck by how little he plays to the viewer. He’s completely uninterested in winning us over, never playing to the camera, which means that he ultimately does win us over a bit as there’s charisma to be found in his standoffish confidence. Hackman’s Popeye is a terrible cop but also a great cop, since he’s so obsessed with justice to the exclusion of all else—including, in many cases, the law. Hackman does nothing to doll up the role. Rather, he’s as single-mindedly dedicated to the role as Popeye is to his job.

Anders: I also rewatched The French Connection this past week, since it had been nearly two decades since I last watched it. I agree that Popeye is a great character. I’m not sure the movie works nearly as well without this jerk of a cop with a twinkle in his eye. I think it’s as much Hackman’s movie as it is Friedkin’s.

Aren: I also watched French Connection II, which I don’t entirely want to spoil for you guys if you haven’t seen it, but there is a long sequence midway through that lets Hackman really cut loose in terms of acting. It’s kind of insane to witness an actor being so pathetic and uncomfortable in such a big role. Furthermore, it’s hilarious to watch Hackman berate random French strangers in Marseilles, try to pick up girls, and even befriend a local bartender by getting him drunk on absinth. There’s a working class honesty to Hackman’s affect that makes him likable even when he’s playing a jerk.

Anton: The 1970s gave us some famous cop characters who range from rough to maybe bad people, and clearly later roles such as Gerard Butler’s “shithead lead” cop in Den of Thieves owe a lot to them.

Aren, do you think Hackman’s Popeye is the best of these types? He might be more realistic than Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry.

Aren: I like Dirty Harry more as a character, but we also get to see him through five different movies (of varying quality). Eastwood also interrogates Dirty Harry more in works like Sudden Impact, whereas we only get two films with Popeye. Popeye might be the most realistic cop of this type, though, which makes sense because he’s based on a real life cop, Eddie Egan. He’s a great character nevertheless.

Anton: It’s been a while since I rewatched it, but in The Conversation, Hackman does a great job of playing a very silent role. He’s watching and listening for most of the movie, and he is able to convey the character without the frequent mugging actors do when they are trying to show that they are paying attention to something.

Mid-Career: The 1980s and 1990s

Anton: Hackman’s work in the 1970s did a lot to set the model for the kinds of roles he often did in the 1990s. A great example is Enemy of the State (1998), in which he basically plays a more paranoid, conspiracy-minded version of his character in The Conversation. As I said in my review, “Gene Hackman is a nice intertextual touch, nodding to his alienated surveillance expert in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 paranoid thriller The Conversation.”

But Hackman does go beyond just photocopying his work in The Conversation.

Aren: His work in Enemy of the State is definitely riffing on The Conversation and it’s one of his most memorable roles, especially in retrospect as everything he says is pretty much true. But let’s not forget his other massive 1990s roles: Crimson Tide and Unforgiven.

Anders: Crimson Tide was the film I turned to to remember Hackman the day we learned of his death. It’s such a paradigmatic Hackman role, with him as the gruff, no nonsense hardass, who we kind of like and respect at the same time. His Captain Frank Ramsay offers a bellicose and rigid view of a military officer: he’s absolutely willing to fire his nukes, and will not brook any dissent, even from the thoughtful and cautious Lt. Commander Hunter, played by Denzel Washington. As he says in the film, “We’re here to protect democracy, not practice it.”

Anton: Wait, I don’t think I’ve actually watched the whole movie, but this just sounds like The Hunt for Red October, but entirely from the American side, no?

Anders: There are definitely parallels, though Red October gives both sides as you note (Soviets and US), and is more about understanding the enemy’s motivation, while Crimson Tide is about the concept of chain of command and how to proceed when orders are unclear. Apparently it was inspired by actual events (on the Soviet side) during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Both films also have classic dialogue re-writes from big directors, with John Milius working on Red October and Quentin Tarantino on Crimson Tide.

But I think that the film is particularly good as a demonstration of Hackman’s appeal because we aren’t necessarily asked to like him, but we understand him. The film works because it offers Ramsay and Hunter as foils for each other. And while the film definitely favours Hunter’s perspective (if only for the rational idea that we don’t want to die in a nuclear war), it is the fact that Ramsay is played by Hackman that makes his ultimate rapprochement with Hunter palatable.

But if Crimson Tide shows that Hackman could be gruff and no nonsense yet redeemable, then earlier in the 90s he played what is perhaps the darkest version of his classic character in Sheriff “Little Bill” Daggett. Just like Ramsay, Bill is devoid of romanticism and calculating in what he sees as meting out justice. But he’s also cruel and without remorse. He runs his town in the Old West with an iron fist. There is no redemption in his character, who kills the protagonists without passion.

Little Bill is a genuinely frightening character, and one of Hackman’s nastiest. There’s a touch of Popeye Doyle to his lawman, but taken to the extreme. It shows that while there is such a thing as a typical Hackman-esque character, he also had range within that archetype between hero and villain.

Anton: It’s been too long for me to really comment on his performance in Unforgiven, but I remember him being downright nasty.

Anders: He might really be Hackman’s most unpleasant character. Apparently his daughters didn’t want him to take on another violent character, but Clint convinced him.

Aren: Yeah, he also didn’t want to do a straightforward western but Clint proved to him that it was a revisionist western. Obviously, in retrospect, working on it was the right call. Little Bill is one of the great movie villains.

Anton: While it’s been a long time since I watched it, we should mention Mississippi Burning, from 1988, in which Hackman plays another gruff, rough lawman, in this case an FBI agent, who is the Southerner and hard-edged agent in contrast to Willem Dafoe’s by-the-book Northerner. So again, Hackman has excelled at these kinds of characters.

2000s: The Royal Tenenbaums

Anton: We’ve talked about Hackman in a lot of thrillers, but one of his best performances came at the very end of his career in a comedy. I’m talking about Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums from 2001.

Now, It might be hard to say who is the better old, sad, gruff man character, Hackman’s Royal Tenenbaum or Bill Murray in Rushmore, but Royal Tenenbaum is one of the great gruff performances of all time. It’s subdued humour done perfectly.

Aren: Is Royal Tenenbaum his best role? Honestly. It lacks some of the rough edges of Popeye Doyle or Little Bill Dagget, though Royal has plenty of rough edges for the lead of a comedy. Hackman is just so good here. His line readings kill me, every time. Consider his devastating reply to Margot as a child when she asks what he thought of her play and the characters: “What characters? This is a bunch of little kids dressed up in animal costumes.” Or his angry, matter-of-fact response to Pagoda, “That’s the last time you put a knife in me! Y’hear me!” It helps that Wes Anderson is great at witty dialogue, but Hackman delivers it in such a unique way. I think in the canon of Anderson films, Hackman and Ralph Fiennes rise above as the characters most uniquely suited to their roles, and who deliver the lines in ways that wouldn’t be replicable by anyone else.

Anton: Anders, as you said to me the other day, it’s not technically his last performance, but it is nice to think of it that way. Thematically, it is a great role to end one's career. Any comments, Anders?

Anders: Royal Tenenbaum might be my personal favourite of his characters, even if it’s one among a number that could plausibly be his best. Aren, just you quoting those line readings kills me and makes me appreciate how Hackman could deliver a line just so. I think he draws out aspects that are there in his earlier characters, the belligerence but with a twinkle in his eye. It’s very easy for me to see Royal Tenenbaum as exemplifying why we loved Gene Hackman.

The brothers discuss how Avatar: Fire and Ash functions as a planetary romance, Cameron’s use of repetition, and the film’s themes and character development.