Halloween Horror: Hellraiser (2022)

In Clive Barker’s original Hellraiser, Pinhead and his demonic Cenobites are little more than window dressing. They are the iconic villains of the film, for sure, but they only interact with the narrative at select points, acting more as judicial entities that wrap up the film’s supernatural elements than as the chief antagonists. If you watch the film expecting Pinhead to be a villain on the scale of Michael Myers or Freddy Krueger, you may be disappointed. David Bruckner’s Hellraiser reconfigures the equation, giving the Cenobites a much more prominent role in his recent reboot of the series. The result is a film that is surprisingly heavy on mythology, while disappointingly scant on psychosexual scares or memorable atmosphere.

Operating simply as a reboot (it’s never elaborated upon whether this takes place in the same universe as the previous films), Bruckner’s film is a flattened riff on the tale for a flattened cinematic culture. Gone are the moody atmospherics, uncanny special effects, and sadomasochistic energy of Barker’s original film. In their place are credible performances, prestige sheen, dour storytelling, and a fixation on the pain of the Cenobites.

Bruckner’s Hellraiser is much better made from a technical sense than most, even all, of the previous films in the series. There are competent visual constructions, well-acted characters, and a genuine command of the material. The gore is disgusting and realistic, and the film takes its story seriously. But Barker’s original film and the first sequel demonstrate the dangerous power of a story fixated on the dichotomy of pain and pleasure. The Cenobites are clearly evil, but the films have often depicted their power as dangerously, psychosexually alluring.

This new Hellraiser never taps into that danger, despite featuring a recovering addict, Riley (Odessa A’zion), in the lead role. Desperate for money, Riley and her boyfriend, Trevor (Drew Starkey), break into a warehouse and steal what they assume are items belonging to a mysterious billionaire. However, all they find inside the shipping crate is a puzzle box, the Lament Configuration, that unleashes the Cenobites throughout the series. Riley solves it and releases the Cenobites, who pull her brother Matt (Brandon Flynn) into their hellish dimension. Riley, Trevor, and Colin (Adam Faison), Matt’s boyfriend, want to get Matt back, so they solve the subsequent configurations of the puzzle box and uncover the clues of its origin, leading them to a vacant mansion in The Berkshires.

The location and the seemingly-haunted mansion evoke a Lovecraftian atmosphere, but where the stories of H. P. Lovecraft and the films he inspired delight in the mysteries of the unknown, Hellraiser, like many of the original’s dreadful sequels, is more enamoured in the mythology of this storyworld than its mysterious potential. It explains rather than suggests, has characters break down the rules in exposition as opposed to being confronted with the terrors of unknown powers and rules acting upon them.

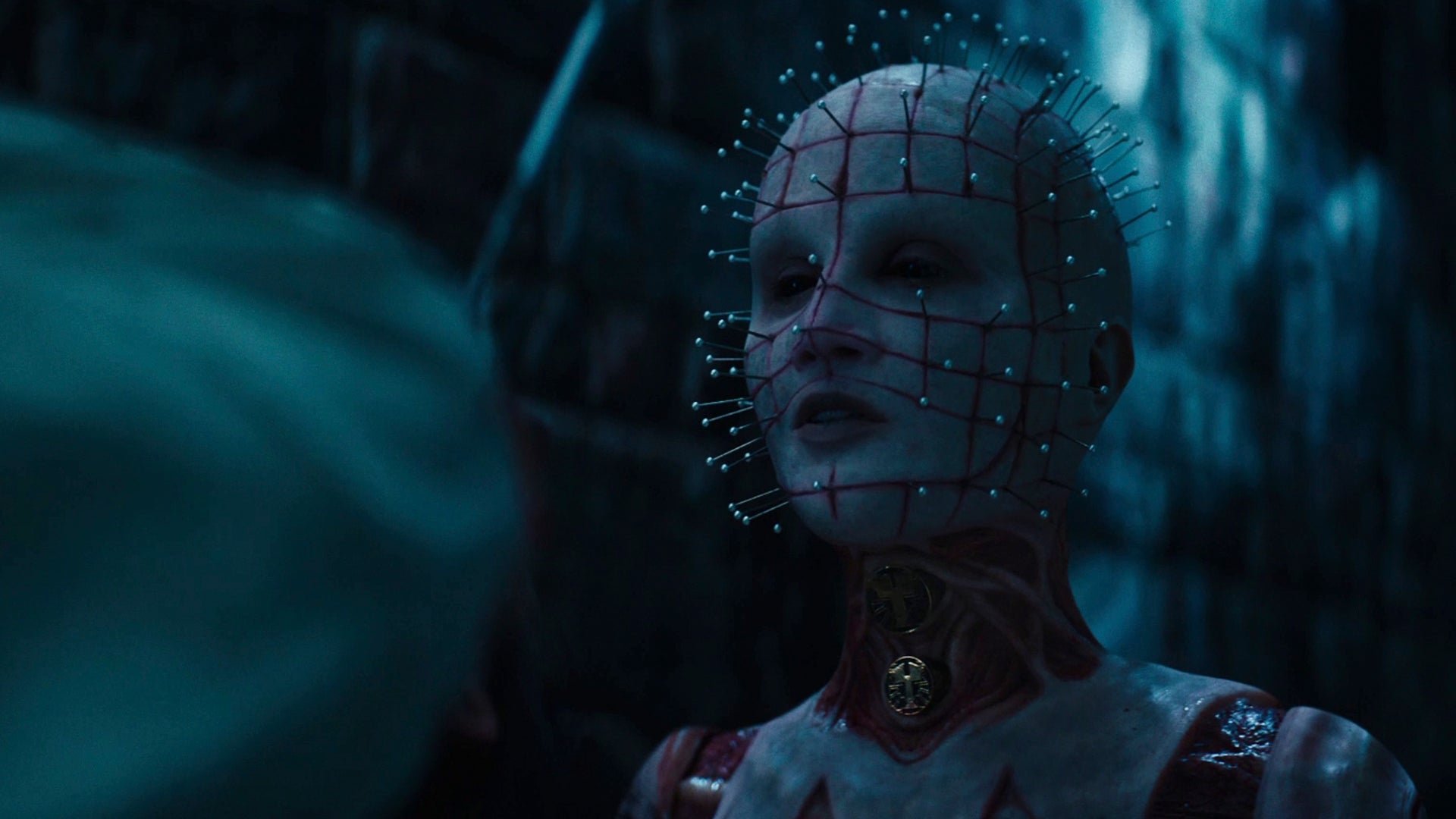

For instance, in the mansion, the characters find a journal that teaches them about the different configurations of the puzzle box and their conceptual connotations. We also learn more about the laws of the Cenobites and their Ancient One god, Leviathan. Perhaps most tellingly, the Cenobites are physically present in much of the film and Pinhead (credited as the Hell Priest and played by Jamie Clayton instead of Doug Bradley) discusses the rules of the box and the obligations of its holder. Most horror sequels get bogged down in mythology, so it’s not fatal for this Hellraiser to explain so much. But the explanations and frequent presence of the Cenobites does defang the terror.

Early in Hellraiser, much of the tension has to do with the unknown and the ways that these horrifying creatures and violent acts intrude upon a credible, realistic world with terrestrial problems. Riley has enough problems in her life and the presence of terrifying monsters calling to her through a playground or stalking her in darkened hallways adds extra stress to an already stressful existence.

But once the film gets to the mansion, the tension mutates into more typical haunted house set-ups; there are shadowy figures down hallways, a mysterious killer, and cat-and-mouse chases and hiding scenes. The most imaginative visual constructions are when the Cenobites break down the walls of terrestrial reality, with the walls of the real world sliding back like the wooden walls of a theatrical set. Bruckner’s visual approach is borrowed from the original film, but arguably more impressive here, especially in a scene in the back of a van, where a victim is isolated in the dark and helpless as she watches the front seats of the van and the back door slide away, pulling the walls of reality forever out of reach. It’s a compelling visual construction and more troubling than the chains and hooks that the Cenobites conjure once the character is trapped in their realm.

However, Hellraiser never complicates its setup, never implicates its protagonists and never forces them closer to the edge to taste the madness of the Cenobites and their world. It’s easy to make demons gross and horrifying; but what Barker does in the original is demonstrate the ways that these demons are manifestations of our own appetites, that if we followed our desires to their furthest extent, we could end up like them. This Hellraiser never does that. As alluded to earlier, the film never taps into the potential of having its protagonist be an addict. Riley is a mess, driven to desperate extremes to eke out a living and show up her overbearing older brother, Matt. She comes into possession of the puzzle box and would be the perfect character to experiment with the sadomasochistic possibilities of its powers, driven by the addictive rush of pushing beyond typical thresholds of pain and pleasure. As the Hell Priest perceptively says late in the film, “There is no retreat once a threshold has been crossed. All you can do is search for greater thresholds.” But she never does that. Riley’s addiction and her conception as a character become thematically beside the point.

It’s a missed opportunity for a film that seeks to correct much of the original series. To be clear, Bruckner’s Hellraiser is still a fair order better than the majority of Hellraiser films. It is creepy and compelling, even if it’s too bogged down in exposition and at least 20 minutes too long. In a cinematic environment flooded with reboots that attempt to recapture the fundamentals of the films that spawned it, this Hellraiser comes up frustratingly short. Barker’s original film gets under our skin, hooks us like the Cenobites do their victims; this one never does.

5 out of 10

Hellraiser (2022, USA)

Directed by David Bruckner; written by Ben Collins and Luke Piotrowski, based on a story by David S. Goyer, Ben Collins, and Luke Piotrowski, based on The Hellbound Heart by Clive Barker; starring Odessa A’zion, Jamie Clayton, Adam Faison, Drew Starkey, Brandon Flynn, Aoife Hinds, Goran Višnjić.

This mockumentary starring Matt Johnson and Jay McCarrol is a complex metafiction farce and a loving portrait of friendship and Toronto.