Roundtable: Halloween Horror: "What scares you?": Debating the Horror Genre

On Horror, Shlock, and John Carpenter

Anton: Aren and I have been itching to hash out “elevated horror” in a roundtable discussion, given our previous comments on the subgenre, such as in his review of Midsommar from 2019, or in my essay on Ari Aster from October 2020.

But since it’s October and we are in the midst of Halloween Horror for the site, I figure we might as well take this opportunity to have a conversation about the nature of the horror genre more broadly, considering not only the works of Ari Aster but also other horror movies we’ve recently watched as examples.

For instance, Anders, you mentioned watching a John Carpenter movie the other night, and I think it might be a good entry point into our conversation.

Anders: Yeah, I watched Carpenter’s Prince of Darkness from 1987, and I was reflecting upon how I really adore Carpenter’s particular approach to horror and filmmaking more generally.

Anton: This is perfect. Because I don’t recall liking Prince of Darkness. I remember the movie as being pretty silly.

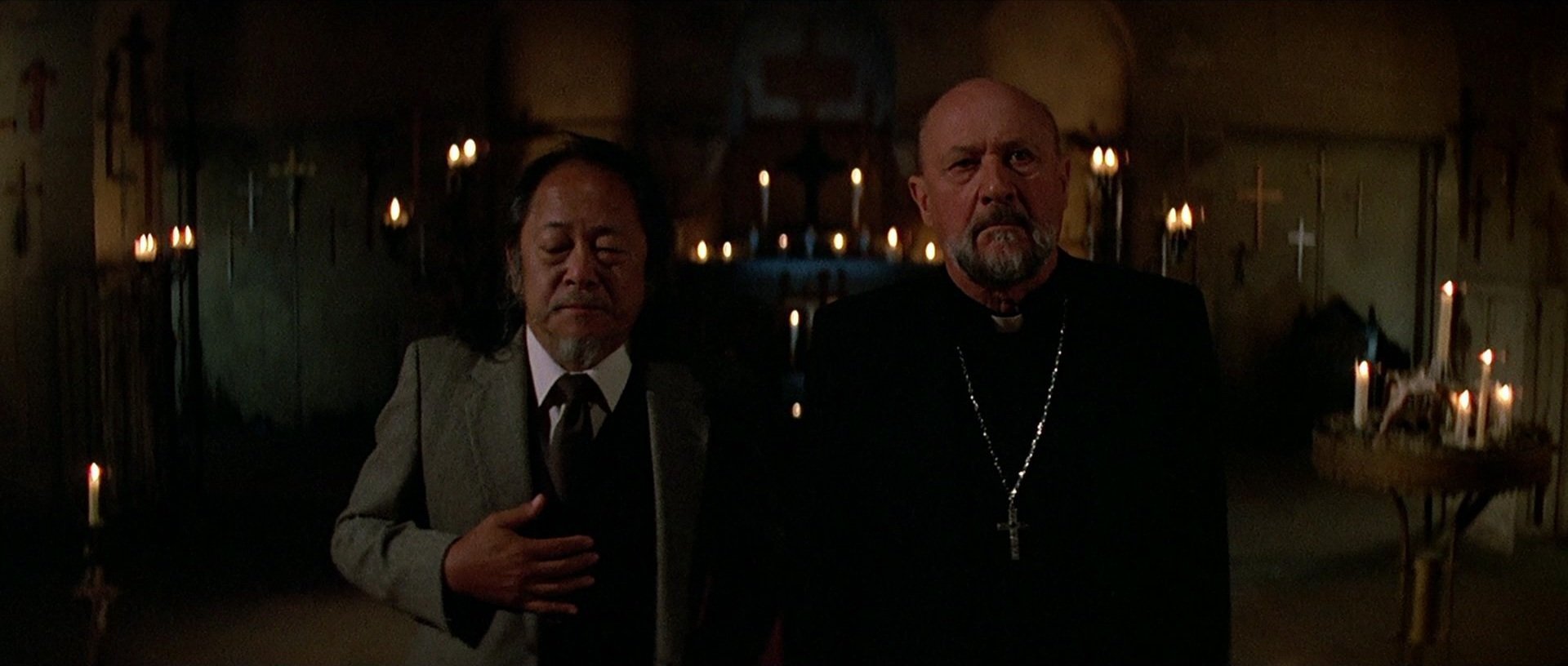

Anders: I liked Prince of Darkness quite a bit, actually. The outrageousness of the premise is part of the appeal. The idea is that a group of graduate students in quantum physics are gathered for a weekend by their professor to join with a priest, played by Donald Pleasance, to investigate a mysterious green liquid hidden in the basement of a church in Los Angeles. The priest is part of an esoteric sect in the Catholic Church, the “Brotherhood of Sleep,” that communicates in dreams and knows the hidden truth of the universe: that the green liquid is the quantum embodiment of Satan himself.

I loved the film’s Lovecraftian themes, of hidden esoteric knowledge and the intersection of science and theology, emphasizing the insignificance of human beings.

Anton: See, I often dislike schlocky horror movies, and I remember Prince of Darkness as looking cheap. But I have to admit, it’s been years since I watched it. In general, I’ve also come to like Carpenter more and more over the years. Take They Live. I was lukewarm on it at first, but now I love it.

I also have a pet peeve with most film portrayals of angels and demons. I get it, you don’t have to be theologically accurate, but the takes are often just so dumb. I remember Prince of Darkness as being somewhat stupid about its portrait of Lucifer. Green goo? Come on.

Aren: See, this is where we probably start to diverge, because I don’t think John Carpenter is all that cheap or schlocky, for the most part, especially compared to most horror filmmakers. For instance, Roger Corman is schlocky. Mario Bava can be schlocky. A midnight slasher from the 1980s like The Slumber Party Massacre that’s all about blood and nudity is schlocky. But I don’t think that’s how I’d describe Carpenter’s films. He’s playing with conventions, but he doesn’t want you to approach his work as trash, upfront. But maybe most horror movies are schlockier than the typical movie.

Anton: I guess it’s fair to ask whether I like most horror movies. But Prince of Darkness is pretty dumb, no?

Anders: The premise is a touch on the schlocky side—to be clear, it’s about Satan being embodied in green liquid and researched by quantum physicists, and that is the kind of schlock I’m into—but the execution is very solid. It doesn’t pretend to offer authentic theological knowledge. It’s basically about investigating a conspiracy about the true knowledge of the universe. It’s science fiction in a sense. I mean, the film involves a message sent back via dreams and quantum computers to warn a bunch of loser grad students about the anti-God!

Anton: And I remember thinking that was pretty goofy and unconvincing.

Anders: Well, what is it trying to convince you of? What’s impressive about Prince of Darkness is despite the wild concept, it manages to be genuinely creepy and atmospheric on a super low budget. Here I’ll agree with Aren, that Carpenter films aren’t meant to be seen as particularly schlocky. They’re often low budget and high concept. But he wants you to engage with the film as a real experience.

And there are real ideas underlying Prince of Darkness. It’s not just a dumb film to unwind with and tune out. The underlying idea, exploring the fear that our growing understanding of quantum physics and challenges to Newton’s physics would potentially have moral and ethical dimensions is interesting. And very Lovecraftian, as I said.

I’ll also say that similar to Lovecraft, Carpenter’s films are too atmospheric and unsettling to be undone by the overwrought or potentially schlockly bits.

Aren: You truly are the target audience for elevated horror, Anton. Producers and companies like A24 seem to be thinking of you when they ask, “How can we make someone who thinks horror is dumb like a horror movie?”

Anton: I don’t think horror as a genre is dumb. I think many horror movies are dumb.

Aren: Fair enough, but many movies are dumb. Comedy and horror just put the dumbness closer to the surface in terms of presentation and story, so it can be more obvious to notice.

Anton: I guess it’s also just not my go-to genre. I don’t unwind and watch horror that often.

Aren: Mostly just in October, right?

Anton: We’ll, I’m required to, for the site.

Aren: The contractual obligations of working on a website with me.

Anton: I enjoy a good scare on a summer night too. I’ve just never understood the interest in some horror buffs to watch horror all the time. Kinda bewilders me. “Time to unwind and see someone get flayed.” Okay?

Aren: See, I’ve come to like unwinding with a horror movie. I always used to get super scared with horror movies, so maybe this was a conscious decision on my part, to defang horror, so to speak, but I now understand there is something weirdly fun about watching scary or gory stuff at the end of a long day. It lets you turn off your brain, if we’re using common parlance. I don’t think it’s relaxing, but it does allow you to be “outside yourself” for a moment, which I think is what people sometimes want with entertainment to unwind. Again, it’s like comedy and the idea of “Turning off your brain and laughing.”

I also enjoy the idea of a movie trying to mess with me, either through scares or twists or just bizarre stuff happening. I’m at that stage where I watch most horror movies with a goofy grin on my face when I’m not feeling super scared. For instance, watching Zach Cregger’s Barbarian recently, I had a lot of fun just taking in the energy of other people in the theatre, witnessing their discomfort and surprise, their shock. It put a big grin on my face where I kind of just thought the whole time, “What sick thing is going to happen next?” Perhaps this means I’m a sicko or something, but there is something emotionally releasing about horror. It provides catharsis in a way that few other movies do.

On Elevated Horror, Style, and Subject Matter

Anton: So, Aren, you said I’m the target audience for elevated horror, and that might be true. Because one thing I like about Ari Aster’s two horror movies—I’m talking about Hereditary from 2018 and Midsommar from 2019—as well as, say, Robert Egger’s The Witch (from 2015) is that these movies are not dumb about their subject matter. They actually take their subjects, whether its demons or paganism or witchcraft, very seriously. They seem to be interested in the subjects themselves, and in fact knowledgeable about them, rather than at best savvy in regards to the horror genre and its conventions, and at worst just cheap and dumb.

Anders: Haven’t seen Midsommar, but I do agree that The Witch is a very serious and smart film that manages to take the beliefs of early Puritans at face value and work through how terrifying that might be. But I think I disagree on Hereditary. I wasn’t as keen on it. I don’t think it’s as smart as it thinks it is.

Anton: What I mean is that it shows evidence of actually researching demonology and such.

But Hereditary is also darkly funny. It has goofball lines and weirdly hilarious moments.

Anders: Definitely made me laugh a few times. But part of that is the disconnect between Aster’s serious subject matter and the stylistic conventions of the genre.

Anton: Most horror seems to be made by people who just know and like horror movies. Fine. Movies are built up on the conventions established by previous works. But I do appreciate the handful of horror movies that appear to actually deeply consider the nature of evil, that really grapple with folklore, that are curious about the possibility of spiritual realities, etc. It gives a whole other dimension of interest to these movies that I don’t find in so many horror movies.

Aren: I don’t entirely agree with that assessment.

Anders: I agree with your first analysis, that horror movies are at their very best when they actually consider the nature of evil and build on folklore and the gothic, etc. Where I disagree is that something like Hereditary is an example of that, actually considering the real nature of those subjects. I felt like the coven/demon stuff was kind of not dealt with seriously. It felt obligatory. What Aster really wanted to deal with was “trauma” and loss, and all that. It didn’t feel fully integrated I guess.

Aren: I think the things that differentiate Hereditary and an old, more conventional horror movie are more a matter of presentation and budget. I think it’s often easier to notice the “silliness” of the subject matter when there’s a bad performance, silly camera move, special effect, etc. But a movie like The City of the Dead is probably as serious about the nature of evil as Hereditary, even if it’s not using references to actual demonic practices and layering its presentation of horror movie evil with domestic stuff like familial abuse.

Anders: Absolutely. But I prefer City of the Dead and its approach.

Anton: So here I will admit my knowledge of the genre is not as deep as either of yours. And I definitely want to check out The City of the Dead. That sounds great. But liking Aster and Eggers doesn’t mean I’m knocking an old movie like that per se.

Take Cat People, directed by Jacque Tourneur and produced by Val Lewton from 1942. There’s an old horror movie that I would consider to be serious and smart about its strange subject matter.

Anders: And again, I love Cat People and all the Val Lewton productions. One of my favourite Octobers ever for viewing was when I watched all those. But those films, while smart, are again quite low budget and sometimes pretty high concept.

But honestly, the issue is that most “elevated horror” films just want to be The Shining or Rosemary’s Baby or The Exorcist. But they aren’t.

Aren: Well, yeah, the filmmakers are just not as good as Stanley Kubrick or Roman Polanski or William Friedkin. But few are.

Anders: Exactly.

Aren: My pet peeve with elevated horror isn’t the filmmaking. The filmmaking is good, if calculatedly tapping into what we consider “prestige filmmaking” at this particular moment. For instance, the framing is moody and evocative; it’s not POV shots, shaky handheld camerawork, low-budget lighting. It’s got the formal precision and curated atmosphere that you get in an Oscar film, the sort of perfectly-centred tracking shots, the ambient score, the naturalistic lighting, the performances by A-list stars and award-winners.

Anders: The elevated horror filmmakers know how to put on the trappings of style.

Aren: For sure, but I have nothing against these formal elements. I may not agree that they’re necessarily more serious cinematically than what we get in a typical film in the 1940s (which is not what I think you, Anton, would argue), but I agree that they are nice elements to watch in a film.

It’s the literalism that I dislike, or materialism, if you would rather use that phrase. The idea that terrestrial, domestic, social horror, etc., is somehow scarier than a demon or a ghost or the forces of Evil (with a capital “e”). Horror movies operate heavily on metaphor and many elevated horror films reduce the metaphor to a one-to-one relationship with some social evil, so that there is no monster that exists in its own right, but simply a characterization of something that the filmmaker feels passionately about in our culture.

Ironically, I don’t think Ari Aster actually suffers from this literalism. He often confuses the binary between “real” and not real. Hereditary is about domestic trauma and family abuse, but it is not just about those things. There is an actual cult at work and actual malevolent spirits who use the domestic failings of the family as a means of manipulating them. Midsommar is about toxic romantic relationships, but it’s not just about that. There is an actual Pagan evil that motivates the Swedish commune.

Anton: Yes, exactly. Hereditary is about how domestic abuse is passed on, and it is about a demon-worshipping cult. It’s both.

Aren: But take Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook, for instance, which is probably one of the most celebrated horror films of the past decade. Its monster is purely a manifestation of the mother, purely a stand-in for her contempt for her child, who is a brat. Once you “solve” the movie, there’s nothing left there to scare you. How can you worry about the monster banging on your door when you realize that monster is just a manifestation of bad feelings, just something that someone can work out in therapy? Even Jordan Peele’s films play in this style, particularly his work as writer or producer and not director, such as the Candyman requel. These films aren’t necessarily bad. I gave both The Babadook and Candyman modestly positive reviews. But they have no curiosity about the nature of evil because they see evil just as expressions of the real world and nothing more.

Anders: Oh man, The Babadook is the worst offender. I think Peele’s Us verges on that, but I hold back from saying it completely does, since I can’t actually figure out what the literal embodiment is meant to be.

Aren: The ending is allegorical, but I’m not sure what it actually stands in for, which is why I find the ending so unsatisfying.

Anton: I need to see The Babadook, which might be the litmus test. What do I really think of elevated horror as a subgenre? Or do I in fact just admire Aster and Eggers?

Before we move on, can we clarify. Do you understand what I mean by a film’s coequal interest in horror as a genre and interest in the subject matter? Surely style is an aspect of it too. And I think this holds for Rosemary’s Baby and The Shining.

Aren: I do. As in, a typical slasher movie is not interested in the mind of a serial killer. Or a ghost movie isn’t really interested in demons. These movies are more about the prurient thrills for the audience, not the actual investigation of the scary thing at their centre.

Anton: Which is partly why I love the Neftlix series Mindhunter. Or The Silence of the Lambs. They are intelligent about serial killers yet also scary.

Aren: But I also think that “serious” trappings are often just trappings, and that the thing you may not like might just be the presentation of the material, not the material itself.

Anton: Perhaps. And M. Night Shyamalan was someone who also, early on, used formal practices to bring prestige to his supernatural stories, even if his later works have been definite B-movies.

Aren: Like, I think elevated horror can border on “self-serious,” in that the handling of the material is not inherently more serious than in a schlocky horror film. But the presentation can make us think the movie is necessarily more “serious” because it looks more similar to other “serious” movies.

What Makes a Serious Horror Movie?

Anton: Let’s circle back to some of our earlier points to see if we can get at something about the nature of the horror genre. Or find some agreement on these issues.

Now, I’ve just dug up what I wrote about Prince of Darkness in my movie journal from August 2009: “A little scary, a little corny, John Carpenter’s Prince of Darkness is a sort of positivist horror film. That is to say, it tries to explain the Christian universal battle between good and evil in material terms, using pseudo-scientific babble.”

Aren: That reads almost like a description of the writing of H.P. Lovecraft. It’s all just “pseudo-scientific babble” about space squids and crazy men.

Anders: I think that’s my issue, Aren. That a serious presentation doesn’t necessarily mean really grappling with the ideas. But I do think that for all its genre trappings, something like Prince of Darkness is genuinely interested in its ideas. You’re not wrong in the description, Anton. I just think that’s actually an interesting idea.

So, I guess I’m agreeing with your assessment of self-seriousness in films.

Anton: But you don’t think Hereditary is serious at all with its demonology and such?

Anders: Not really. It felt tacked on.

Aren: It felt a step beyond, say, the internet searches of Paranormal Activity, for sure. But I also think the ending kind of betrays the real intentions, which is that it’s all just an excuse to light a person on fire and have someone crawling on the ceiling like in any horror film. So I find it a bit more typical than you do, perhaps, Anton. And I ultimately think a movie like Paranormal Activity is much better, and much scarier.

Anders: In my review on Letterboxd, I said that Hereditary “Ends up feeling double-minded, as the ending robs the film of any thematic resonance.”

Anton: I spent some time reading up on the material after, and that convinced me that Aster was smart about his subject matter. For instance, it’s a historically-mentioned demon at the end. But then Aster puts the demonology together with the story about this intergenerational cult and family abuse. I find that very compelling and creepy.

Anders: It is smart enough to use a “real name,” etc., which gives it more “authenticity.” It’s true.

Anton: The ending reveals what the story has really been about the entire movie.

Aren: Yeah. But it’s just another way of getting to the same place in a story of possession and demons. I don’t mind other movies that don’t spend an hour on family abuse narratives before getting to the possession stuff. These are just different, valid approaches to similar material.

The actual use of Paimon is cool though. Aster does that even more in Midsommar, trying to get specificity in the horror, which I appreciate. But then there’s another problem in Midsommar, which is that it becomes overstuffed and absolutely fixated on one way of presenting horror. I wanted to yell at Aster when watching it, “Trim this thing down man!” Haha

Anders: Well, if we’re talking about movies that can be considered elevated horror, I’m looking forward to re-watching The Exorcist films this October. I’m especially curious to see how Schrader deals with the demonic in his prequel. I’m also interested in Blatty’s third film, because I like his The Ninth Configuration a lot.

Anton: I’ve always appreciated how The Exorcist was also fairly accurate in its portrayal of priests and Catholicism. It has sensational stuff, to be sure, but I’m more scared because the movie makes me think it’s real.

Anders: But then you are also getting into issues of belief. If someone believes in demons, or ghosts, etc. that will impact their reaction to a movie.

Anton: For sure. But that doesn’t stop many strict materialists from adoring horror. Although the attraction might be different.

Horror as a genre is also like comedy, as Aren always says. Some of it can’t be over-intellectualized. It’s working on ways we don’t entirely understand. Affecting our emotions and gut, our instincts.

To pause for a moment, however, can we agree that Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist, and The Shining are the essential antecedents for modern elevated horror? If I’m correct, they were also the first horror movies to be elevated from sort of sidelined genre fare to Academy Awards and critical adoration.

Anders: This is correct. The Exorcist was nominated for the Best Picture Oscar and was the highest grossing R-rated film for a long time. There’s something here also, though, where as the horror genre evolved from the Gothic genre, it branched off. You get the more “materialist” and psychological films like Psycho and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, that eschew the supernatural for modern fears. What’s interesting to me is how films like Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist return a kind of Gothic fascination to horror. I think Aster’s films have a touch of that two with conscious throwbacks to films of the 1970s: The Exorcist and The Wicker Man for instance.

Aren: They do dig into the classic antecedents of the genre, in terms of both film and literature, such as Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw, which is a ghost story, but not necessarily a horror story. With film, Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist, and The Shining are key touchstones, for sure, but I’d hesitate in actually labelling them as elevated horror. I think elevated horror is distinct to the 21st century, when Rotten Tomatoes scores and the Internet shone a spotlight on the general negative bent of film criticism towards horror, which clashed with the typically high box office receipts of horror movies. So in reaction, studios started to want to package their horror films as prestige films in order to get better critical reception. But that’s a larger discussion about the genre.

Anders: I do get what you’re trying to say though, Anton. What I’m just noting is, don’t get confused that a serious presentation is the same as having serious ideas.

And to go back to the start, I think Carpenter does explore serious ideas on a low budget better than most. Like take They Live. Super hokey and funny at times. But deadly serious about the idea of ideological class war. But can you imagine how exhausting it would be if it was serious form-wise? I think you’d have problems similar to Us.

Aren: I’d be curious about your response to Ti West’s movies, Anton. Since he does kind of straightforward horror movies, but also tries really hard to do the serious aesthetic approach so you aren’t distracted by dumb shit that would pull you out of the plot. The House of the Devil, The Innkeepers, X, and Pearl all try really hard at verisimilitude for Satanic panic, ghost stories, slashers, and Golden Age Hollywood, respectively.

Anton: I need to see those.

So, to be clear, my comments about Prince of Darkness are based on a viewing of the film over a decade ago! I admit, I’ve since come to see John Carpenter as being more intelligent than I originally thought. And yes, self-seriousness can introduce other problems to a film. I just don’t recall thinking Prince of Darkness was smart about anything, or a particularly good Carpenter movie. I’ve now also read much more Lovecraft. Perhaps I’d have a different view of the themes today.

But take a movie like Roman Polanski’s The Ninth Gate. At times, the film’s stupidness messes the whole thing up.

Or The Prophecy. It’s conception of angels is so dumb it ruins the whole premise.

Anders: Oh The Prophecy is a terrible, terrible film.

Aren: The Ninth Gate has such good atmosphere, but it becomes really dumb by the end. I enjoy the movie on the whole, but I also am bothered that it’s not better and that it ends in such a dumb place. But don’t you think that one of the things that holds it back is that it presents itself as this prestigious, serious horror movie about occult books and then follows stupid narrative directions, so it doesn’t seem of a piece? It’s like elevated horror and schlock mixed together, which becomes something kind of mediocre. Like, Polanski has you thinking you’re watching something like Rosemary’s Baby, and then it devolves into a lame version of some B-rent Italian schlock, and you feel kind of cheated.

Anton: In The Ninth Gate, the style and matter are actually at cross purposes. The prestige-style filmmaking supports a great atmosphere. But it’s not completely smart. For example, I remember being so annoyed by Johnny Depp’s book collector just tossing around the rare old book in his satchel.

Anders: I’d like to revisit The Ninth Gate having now seen more Italian giallo.

Aren: Yeah, the ending is very much in the style of Mario Bava. But Bava is consistent. The thing that holds Bava back is that his films are extremely low budget, so they’re often just ugly and poorly performed. But what he’s doing with the camera and the confidence of his storytelling choices are pretty impressive, in my opinion. If only we could get a nice remaster of one of his films. I’d love to see Black Sunday or Black Sabbath in a theatre one day.

Anders and Anton discuss their appreciation of the third season of The Bear and the mixed critical reception to the latest season of the hit show.