Review: La Strada (1954)

La Strada is a beautiful film. It’s sad but also alert to the power that the basic elements of life have in binding us together and providing joy, whether that’s in food, play, religion, or art. It’s worth noting that Federico Fellini had worked as a co-writer and collaborator with Roberto Rossellini on Rome, Open City and Paisan, and so helped lay the foundations for the Italian neorealist tradition of filmmaking. Traces of the movement’s deep humanism and focus on social realism still remains in La Strada, which showcases the travails of regular people making their way in the aftermath of a war-ravaged Italy. But the existential malaise and playful extravagance that would mark some of Fellini’s later films is also developing in this film. In La Strada, life is hard, brutal, and offers no guarantees, but a joke, a drink, and a show aren’t just a distraction, but the way of life.

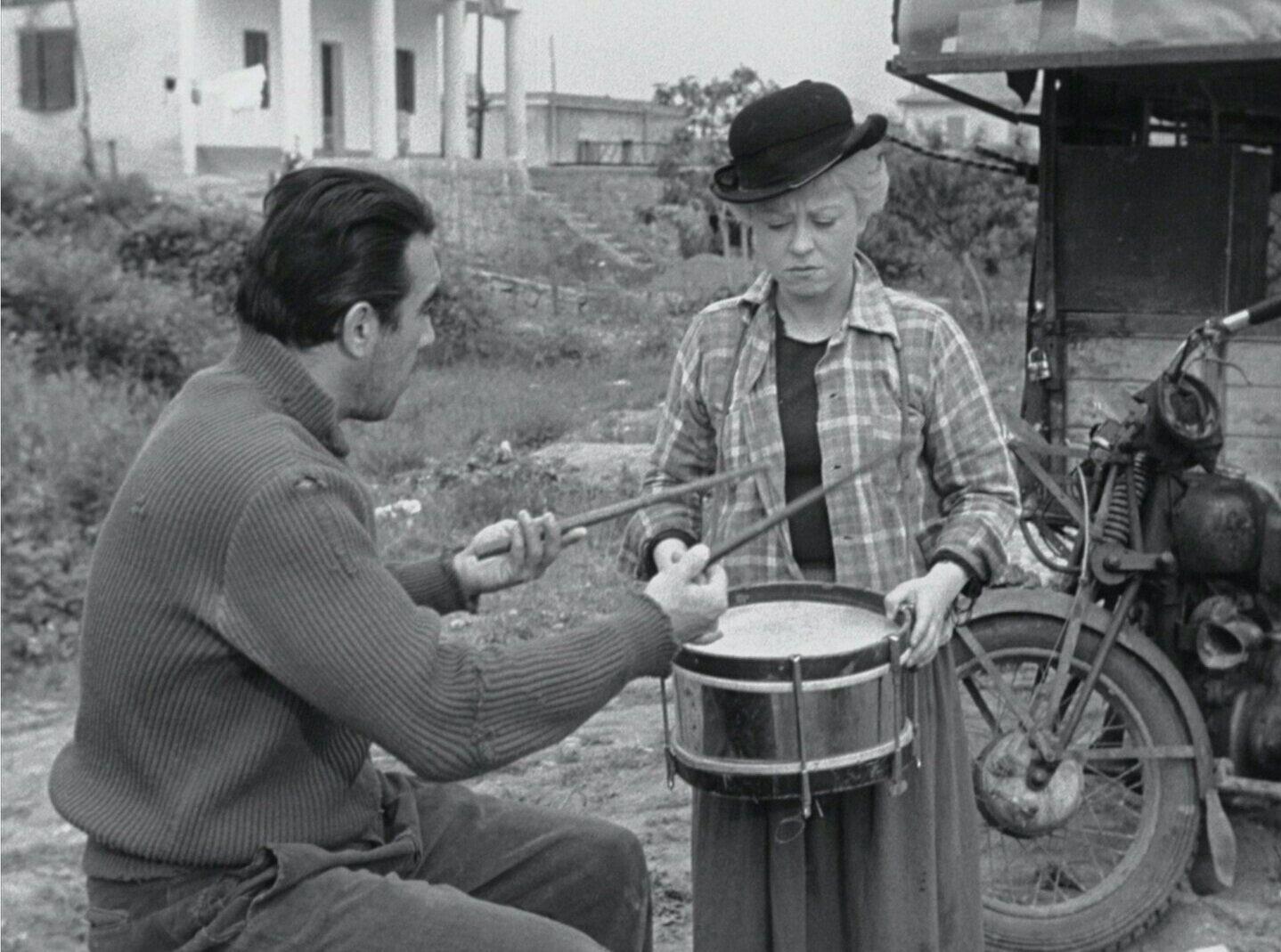

Set in post-war Italy, La Strada tells the story of a young woman, Gelsomina (Giulietta Masina), who is purchased from her mother by the travelling strongman Zampanò (Anthony Quinn) to act as his performing companion and sidekick. Moving from town to town, Gelsomina performs comic musical introductions to Zampanò’s strongman act, while putting up with his abusive treatment and his philandering indifference to her as anything resembling an actual wife or partner. Her role is to domesticate their vagabond presence, granting them access to spaces that a single man or unmarried couple in Catholic Italy wouldn’t normally have.

Seeking a way out from the life of a travelling performer, Gelsomina encounters, Il Matto, “the fool,” (Richard Basehart), whose light heart and kindness contrasts with Zampanò’s bitterness and violence. Zampanò and Il Matto are constantly at each other’s throats, Il Matto ultimately leaving a deep sense of resentment and humiliation in the strongman that will come to haunt them later.

La Strada is structurally, and titularly, a road film; “la strada” literally means “the road” in Italian. As a road movie, its plot is driven by the need to secure the next gig, the next meal, a place to lay one’s head. Gelsomina’s willingness to go along with her mother and Zampanò’s transaction shows the viewer just how desperate and driven by necessity life was for many people in post-war Europe. Today we may recoil at the callousness and desperation that drives such behaviour, but it was simply a matter of life and death, and one less mouth to feed and a few lira makes a sad kind of sense in the world of the film. It’s worth considering that this world isn’t some distant or fantastical dystopia, but the world as it existed at the time of your grandparents or great-grandparents’ youth; and not in some far-away land, so easily exoticized and dismissed, but in what today we think of as a central nation of Western Europe. How fragile and recent is our comfort and sense of superiority today?

Related to this post-war setting, much of the film centers around the loss of any kind of legitimate masculine authority in the aftermath of a war that showed the emptiness of fascism and destroyed a generation of men. Women and those on the margins still manage to function and maintain societies amid the brutality of a damaged and fragile masculinity that remains. Consider the mother of the bridegroom at the wedding, who notes she’d been married twice before, and rebuffs any suggestion she should marry again (though she isn’t put off by the idea of Zampanò fulfilling a particular masculine function nonetheless). More importantly, the nuns who offer Gelsomina and Zampanò a place to stay one evening function as a kind of feminine moral anchor in the world, noting that their convent has existed for nearly a thousand years even as the individual nuns are moved from place to place every few years to remind them of their true allegiance to God, and not to grow too attached to anything. Gelsomina, in whom they see a kindred spiritual seeker, is invited to join them, but she turns them down.

Such elements of social realism certainly contribute to the greatness of La Strada, but what marks it as a standout film in cinema history is first and foremost the two central performances by Anthony Quinn and Giulietta Masina. Quinn, a Mexican-American Hollywood mainstay at this point in his career, went to Italy to try his hand at something a bit different, playing the brutal and self-loathing Zampanò. The casting of non-Italians in these productions is a reflection of the use of non-synchronous sound in almost all Italian films of the period (a holdover from the fascist pro-Italian policies of Mussolini to ensure all films were dubbed in Italian); Il Matto is likewise played by American actor Richard Basehart (probably best known for the sixties television show, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea). Quinn shows an ability to lean heavily on his physical performance to give Zampanò a sense of more than just a brute, but a man who is brutal because of his fears of losing his independence and freedom; he does this with his searching eyes and body language, culminating in his rage against the waves at the film’s end. The fragility and fear that underlies his character is essential; without it, his climactic act, the one among the many horrors he commits that he ultimately cannot forgive himself for, is rooted in that fear and weakness rather than callousness or cruelty.

But it is Masina’s Gelsomina who is the true centre of the film. Masina, who was Fellini’s wife at the time, plays Gelsomina as the naïf who must maintain her spirit in the face of the world’s brutality. Despite being sold into service, she self-identifies as an artist, demonstrating a love and talent for music and making people laugh. Fellini, in contrast to Anglo-American sensibilities, had a great deal of respect for what we consider the circus performer, rooted in the Italian commedia dell'arte, the comic and burlesque form of theatre that had flourished in Italy since the middle ages, and this is seen in later films as well. There is a respect given to the ability to improvise and mock the conventions of society. Masina, wearing an oversized coat and shoes and with her face painted like a clown, somehow manages to imbue the figure with a kind of dignity rarely seen in cinema, as Fellini never positions her as a figure of mockery. In the brutal world of the film, laughter seems more of an affirmation of humanity than being stoic.

The closest thing I can compare it to is Chaplin’s The Tramp—both Gelsomina and The Tramp being naive and joyful figures in the midst of a changing and brutal world. Masina’s eyes and smile, her expressiveness and ability to display clear emotion do so much of the work in the film of communicating her character. Somehow she is able to be both funny and sad in a profound way that the sad clown so rarely is. Today, we no longer trust the clown; clowns are sinister now. But in La Strada, profundity emerges unexpectedly, as when Gelsomina plays the trumpet beautifully. But that beauty isn’t always appreciated in the moment.

Like many of the best neorealist films, La Strada is melodramatic, in the sense that its emotional tenor is rooted in the suffering of the moral figure, the abuse of the hidden and ignored who actually are the ones who can offer redemption to the world. Gelsomina isn’t simply a victim. Her insistence on her role as an artist is one way that she can claim some agency in the world. Gelsomina’s triumph isn’t in her ability to redeem Zampanò or save herself, but in the moral and spiritual truths she reveals in her life to us, the viewers.

I decided to finally watch La Strada for the first time because of the recent piece on Fellini by Martin Scorsese in Harper’s magazine, in which he praises Fellini’s mastery of the filmic elements of camera and sound. I could similarly praise the staging and camerawork in the film, the way that Fellini uses cinema to plunge the viewer into this harsh world, and shows the mastery of film form that would be foregrounded more directly in later, more cinematically self-reflexive films like 8½, though it is no less masterful here. But La Strada left me with more than just a formal admiration for the man Scorsese calls, “Il Maestro.” It moved me and made me appreciate the journey of life and the bittersweet joys, failures, and triumphs we all must encounter on its road. It’s harder to offer much greater praise than that.

10 out of 10

La Strada (1954, Italy)

Directed by Federico Fellini; story and screenplay by Federico Fellini & Tulio Pinelli; starring Giulietta Masina, Anthony Quinn, Richard Basehart, Aldo Silvani, Marcella Rovere, Livia Venturini.

George More O’Farrell’s The Holly and the Ivy is a perceptive Christmas drama that deserves a place in the Christmas rotation.