Review: The Last of the Mohicans (1992)

The Last of the Mohicans is a film of great passion. It belongs in the historical epic romance genre and like all good historical epics it is full of grand-scale filmmaking and sweeping romance. While its narrative coincides with the French and Indian War of the mid-eighteenth century, its themes aren’t limited to its historical period. It finds great interest in the particulars of the time period, especially the way Aboriginals and settlers coexist with the imperial powers that supposedly control them. But it’s mostly fascinated in how passion intersects with duty, causing people to test their convictions against the things they hold dear.

Michael Mann’s adaptation of the James Fenimore Cooper novel and the 1936 screenplay based off the same is set in 1757 in the British American colonies. This was the time of the French and Indian War, when Britain and France battled over dominion of eastern North America. Charged with bringing a regiment to Fort William Henry, the stodgy Major Duncan Heyward (Steven Waddington) sets out under the guidance of Magua (Wes Studi) to bring his men safely to the fort. Also under Duncan’s care are Cora (Madeleine Stowe) and Alice Munroe (Jodhi Mae), daughters of the colonel in command of Fort William Henry. Duncan is in love with the one daughter, Cora, even if she doesn’t reciprocate his affections, and hopes that impressing the father will win favour with the daughter.

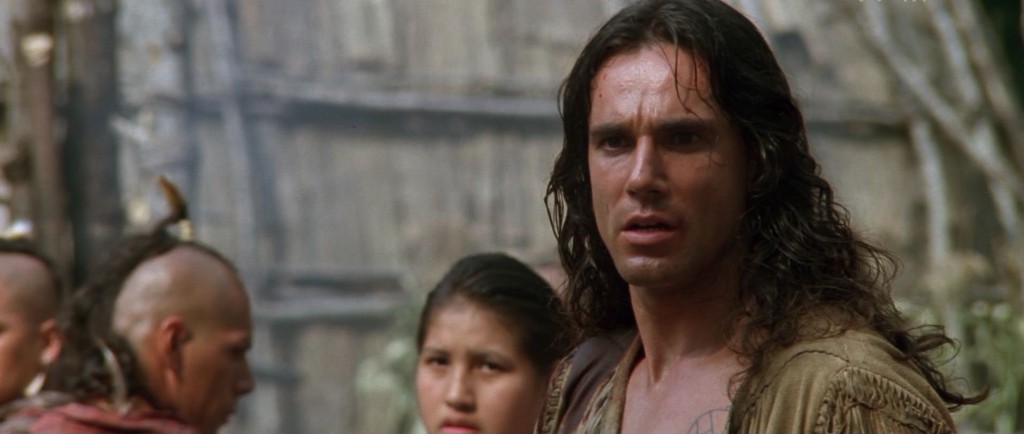

However, on the way to the fort, Magua betrays the English by leading them into a Huron trap. The Huron kill the entire regiment, save for Duncan and the Monroe girls who escape unharmed due to the intervention of three Mohican trappers, Hawkeye (Daniel Day-Lewis), Uncas (Eric Schweig) and Chingachgook (Russell Means). The Mohicans escort the English trio the safety of the fort, all the while Cora and Hawkeye grow closer in affections.

The Last of the Mohicans has not lingered in the cultural consciousness years after its release. While it was a critical and commercial success when it was released in 1992, winning an Oscar for Best Sound and ranking 17th at the domestic box office, it rarely comes up in critical conversation. Part of this is due to how strange it superficially seems next to the rest of Michael Mann’s filmography. But once you start dissecting the themes and the filmmaking, it makes much more sense Mann would tackle such material.

Primary among these themes is the way passion can supersede duty and drive people’s actions. Everyone in The Last of the Mohicans has a duty that’s meant to dictate their lives. Cora Munroe has a daughter’s duty, which in that time period would likely mean bowing to her father’s wishes and marrying Duncan Heyward despite her lack of affections for him. Duncan has a duty to the English crown, as do most of the inhabitants of the British American colonies. The villain Magua has his duty to the Huron nation. Hawkeye has a duty to his father and brother, to preserve their heritage even if he doesn’t share it by blood. The frontier settlers who comprise the militia at Fort William Henry have duty to the crown as well, but their passion lies at home with their families who are now prey to the Huron attacks.

All the character’s passions lie outside of their duty, save perhaps Duncan Heyward’s. Hawkeye and Cora fall in love, despite the irregularity of a gentleman’s daughter falling in love with a white man raised by Aboriginals. Magua in particular is a creature of passion, mercilessly hunting down Colonel Munroe to get revenge on him for the death of his family. The Last of the Mohicans strikes a delicate thematic balance, turning every relationship and character moment into a meditation on passion and duty without reflecting upon these themes through clumsy exposition.

All this makes for a thematically rich film. Luckily, The Last of the Mohicans is also a rousing adventure in addition to a fascinating one. Daniel Day-Lewis makes for a great action hero, his physical acting style translating well to the action cinema athleticism required of him here. I like to think of an alternate world where Day-Lewis took a different career path, full of action roles instead of Oscar-winning dramatic turns. I’m happy with the roles we got from him, but he would have excelled on a larger canvas as well.

To complement the adventure, the film boasts beautiful music and visuals. Trevor Jones and Randy Edelman’s score is one of the best of the 90s. And Dante Spinotti’s cinematography is a real feat, transposing Mann’s clean action frames into the colonial context without losing their visceral impact. One of the best visual touches in the film is the natural lighting. Not a single frame in the film contains artificial light (or at least doesn’t seem to). The sun or flames from torches and candles light every shot.

I even find the film’s tackling of Aboriginal issues more nuanced than immediately apparent. It never condescends to the Aboriginal characters, and while Hawkeye shares traits with other white saviour characters like Lieutenant Dunbar (Kevin Costner) in Dances with Wolves and Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) in Avatar, the context of his inclusion in the Mohican society differs from these other white saviour examples. He is not an outsider who first encounters the native culture at the beginning of the film, but a person who was raised in that culture from the earliest moments of his consciousness. As well, for all his bloodlust, Magua is even allowed sympathy and complexity. His vengeance is more pure than the arrogant imperialism of Montcalm or Munroe. Despite his rage, his flaws afford him added humanity instead of robbing him of it.

The Last of the Mohicans is possibly Michael Mann’s best film. It’s rousing, gorgeous and full of nuance amidst its fast-paced 117 minutes. It’s a little-remembered film that deserves to be recognized as one of the best historical epics of the modern era.

9 out of 10

The Last of the Mohicans (1992, USA)

Directed by Michael Mann; written by Michael Mann and Christopher Crowe based off the novel by James Fenimore Cooper, the adaptation by John Balderston, Paul Perez and Daniel Moore and the 1936 screenplay by Philip Dunne; starring Daniel Day-Lewis, Madeleine Stowe, Russell Means, Eric Schweig, Jodhi May, Steven Waddington, Wes Studi, and Maurice Roeves.