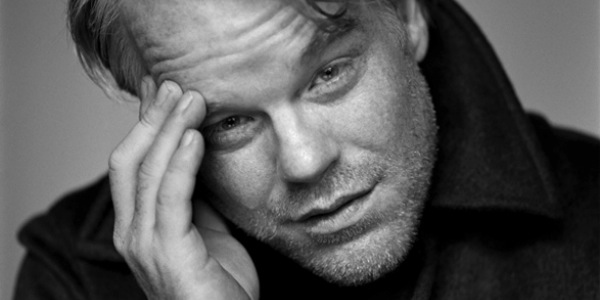

Remembering Philip Seymour Hoffman

Aren: There has never been another actor like Philip Seymour Hoffman and there probably never will be. Many of the great leading men of today seem like contemporary versions of classic great actors. Think of how Brad Pitt reflects Robert Redford, or Christian Bale a young Robert De Niro. But Philip Seymour Hoffman was all his own. He was a Hollywood leading man who got to the front of the cinema without a pretty face or a famous pedigree. He huffed his way through bit parts, showcasing his talent and his mind-bending range through the mid-90s and early 2000s before finally making it to A-list and nabbing an Oscar with Bennett Miller’s Capote (2005).

Now that Philip Seymour Hoffman is gone, tragically robbed from the world by addiction, that monster lurking under the skin of so many sad people, it’s difficult to reflect on what made him so special. My initial reaction to whenever Philip Seymour Hoffman arrived on screen was that the movie would be made better simply by his presence. Take for example a scene in the recent Catching Fire (2013), where Hoffman’s Plutarch Heavensbee pulls Jennifer Lawrence’s Katniss aside at a gala party in the Capitol. Heavensbee himself is a shallow creation, a manipulator whose allegiances are purposefully hidden from the audience. But in the brief conversation he has with Katniss, where Heavensbee masks his intentions and gives her coy warnings regarding the upcoming games, Hoffman brings alive a playful ambiguity.

Hoffman never phoned it in. He took as blank a character as Heavensbee and turned him into the most fascinating character on a screen shared with Jennifer Lawrence. Thus, it stands to reason that when a part with real substance, as in my favourite of his roles in Doubt (2008) or The Master (2012) or Mission: Impossible III (2006), came along, he took every advantage of the opportunity and turned in a masterful performance.

Anders: The loss of Philip Seymour Hoffman took me completely by surprise. Obviously I wouldn’t compare it to the loss that family and friends feel, but to the world of contemporary cinema the loss is real. Hoffman made it that way through what he brought to each role he took on. If pushed to create a short list of my favourite contemporary actors, he would be near the top.

One of the many testaments to Hoffman’s talents lay in his endless versatility. It would have been easy to pigeonhole him as a stock character; his generally portly demeanour and ability to evoke a world-weary sadness could have had him playing variations on the same type, a fate that befalls many who start out as supporting character actors. But instead he broke out from that and was able to portray characters as diverse as the puckish Truman Capote, for which he won his leading role Oscar, to following that role up as the imposing villain opposite Tom Cruise in the third Mission: Impossible film (2006). His character, Owen Davian, is truly threatening and makes good on his promises. While so many action franchises try to up the stakes through screenwriting cliches and overhyped action, Hoffman’s performance alone achieves raised stakes. It was an interesting career choice for Hoffman. The result was one of the best action movie villains of the last decade.

Hoffman’s willingness to push himself as an actor was rewarded in his multiple collaborations with director Paul Thomas Anderson. Beginning with a walk on cameo in Hard Eight (1996), the following year he gave a memorable turn as the unfortunate Scotty J. in Anderson’s Boogie Nights (1997). In Magnolia (1999), as nurse Phil Parma, Hoffman acts as one of the beacons of human compassion. Particularly one scene where Phil desperately tries to get ahold of Frank T. J. Mackey (Tom Cruise, who he would work opposite again in the aforementioned M:I-III) on the phone to talk to his father, the dying Earl Partridge (Jason Robards). This was followed by playing the Mattress Man, the foil to Adam Sandler’s Barry Egan in Punch-Drunk Love (2002), a change of pace, putting Hoffman in an unsympathetic role.

But one of Hoffman’s greatest roles was what was to be his final collaboration with Anderson in The Master (2012): the role of Lancaster Dodd, the thinly veiled stand in for Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard. Rather than a mere caricature, a cartoonish cult leader, Hoffman imbued Dodd with a full range of humanity: his charisma is evident, his failings are ones that are all too human (pride, substance abuse, anger) rather than ones to be easily dismissed and mocked. Hoffman makes you understand why people like Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix) would fall under Dodd’s spell, and lets you see the man’s incredible intellect and rhetorical skill. Few actors can combine the mix of strength and weakness so potently.

Two of my other favourite roles from Hoffman are both ones where he brings something special and unique to a role where you couldn’t imagine anyone else playing it. In Doubt (2008), Hoffman plays the embattled Father Flynn, a priest accused of some unnamed but strongly implied crime by the imperious Sister Aloysious (Meryl Streep). Hoffman plays Flynn not as a creep or a pure saint. It speaks volumes to this performance that the entire film hinges on Hoffman’s ability to embody ambiguity in a human being. In Almost Famous (2000), Hoffman gives what is perhaps his most quotable role as the real-life rock critic, Lester Bangs. His offer of friendship to the young William Miller (Patrick Fugit) and the sage advice, delivered in a wry and gravelly manner that Hoffman specialized in, resulted in such gems as his speech about being “uncool.” It’s touching and funny and everything that the role needed to be.

Looking back at what I’ve written the repeated praise that I offer for Hoffman is that he was always able to bring out the humanity in every character he played. Is it too much hyperbole to say that even with the Oscar, Philip Seymour Hoffman was an underrated artist?

Aren: There are so many of Hoffman’s performances that stick in my mind. I already mentioned his work in Doubt (2008) and Mission: Impossible III (2006) as being some of my favourites, and Anders elaborated why his role as Lancaster Dodd in The Master (2012) is so marvelous. It’s the opposite of the sad sack he often played in his supporting turns. He commands the screen in that film, with his voice, his eyes, and his charisma. His turn as Lester Bangs in Almost Famous (2000) was probably my first introduction to Hoffman. I’ll always remember his speeches in that film, as will many other film fans. But my favourite of his supporting roles probably have to be Scotty J. in Boogie Nights (1997) and Jacob Elinsky in 25th Hour (2002).

Both roles share a lot in common. They’re both defined by their yearning for love. They’re both pathetic, in the true meaning of the term. Scotty J., the naive, eager boom operator in the porn empire of Boogie Nights (1997), pines after Mark Wahlberg’s Dirk Diggler. Eventually he makes his move, drunkenly in a parking lot, and Dirk predictably rejects him. The rejection is shattering, most of all for Scotty’s berating himself as an idiot—it even moves Dirk to compassion. In 25th Hour (2002), Jacob Elinsky is Monty Brogan’s (Edward Norton) best friend, a ordinary school teacher who has inappropriate ambitions after his smartest student (Anna Paquin). Out at the club with Monty for his final night before jail, Jacob makes his move on Paquin’s Mary and the resulting humiliation only highlights Jacob’s unhappiness with himself.

Both Scotty J. and Jacob place their self-worth on their relation to the people they admire, but once they act on that admiration, they’re reminded of their own patheticness, only making them burrow deeper into themselves. It speaks to Hoffman’s skill as an actor that neither character comes across as creepy or unsympathetic. As well, for playing two characters in two films with very similar story arcs, Hoffman never repeats himself. He made everything new. His supporting characters almost always overshadowed the leads of the films. They were the most recognizably human.

That’s what Hoffman did for his characters. He made them real. An actor can’t aspire for anything greater.

Rest In Peace Philip Seymour Hoffman (1967-2014).