3 Brothers’ Essential Films of 2023

Another year in cinema has come and gone. Alas, as is always the case, we didn’t see everything of interest. But there were many noteworthy films that came out in 2023, some of which ought to be viewed as essential. That’s why we’ve got this list, which collects all the worthwhile movies of the past year (that we saw) in a single spot.

The criteria for inclusion on the list has been the same since we started this exercise in 2013:

1. At least one of the Brothers must have seen the film and ranked it good to great. No one has seen Justine Triet’s Anatomy of a Fall or Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Monster yet, so you won’t find them on the list.

2. If more than one Brother has seen the film, then there needs to be agreement on its quality; films that we disagreed on don’t make the list. So no Asteroid City or Napoleon, which you can hear us debate on past episodes of 3 Brothers Filmcast.

3. No lukewarm or mixed reviews on the list, no matter how popular the film or how much it dominated the discourse. Sorry, fans of Barbie (which is only fine). It ain’t happening.

Here are the 3 Brothers’ Essential Films of 2023.

The Prestige Pic

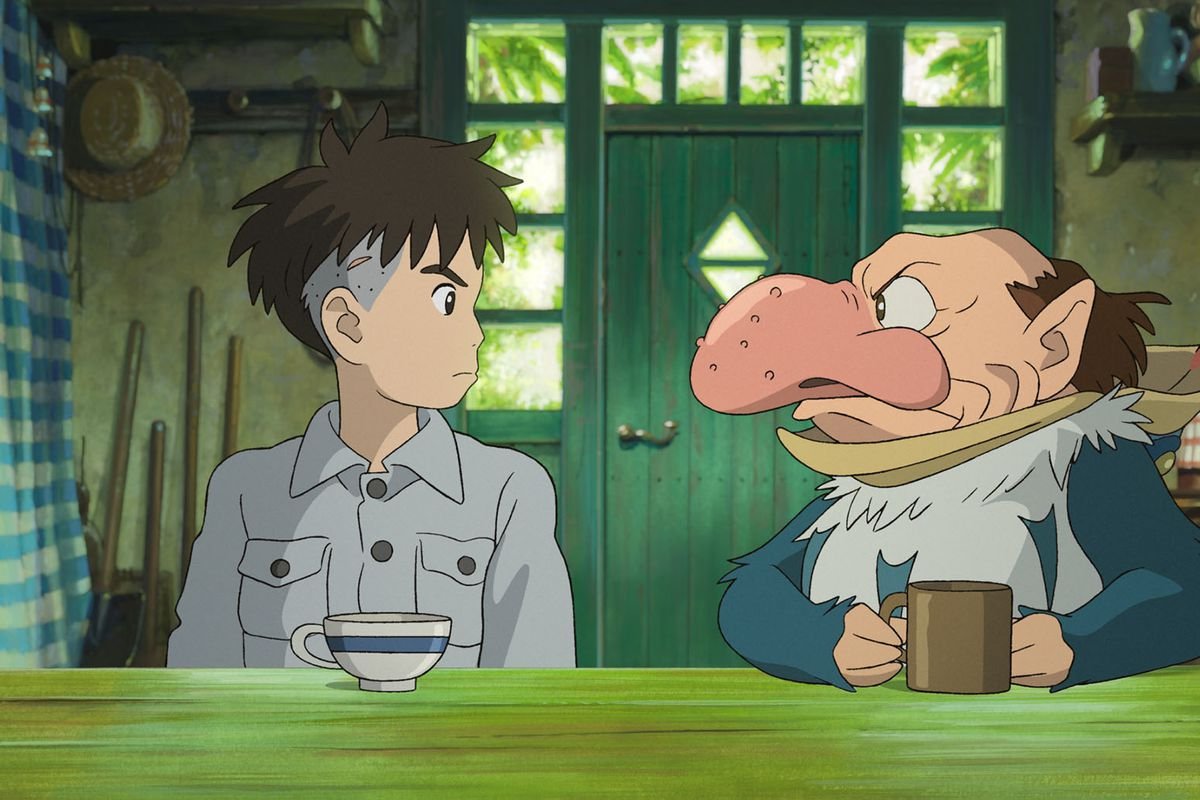

The Boy and the Heron (dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

“‘How do you live?’ This is the formative question posed by Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron (and the Japanese title of the film). The Japanese master of animation returns 10 years after another false retirement and supposed swan song, The Wind Rises, with a film that, at first glance, looks like a grab bag of Miyazaki storytelling obsessions. A 12-year-old boy, Mahito Maki (Soma Santoki), staying in the country with his father (Takuya Kimura) and his new wife, who happens to be his aunt (Yoshino Kimura), enters a magical world to rescue this new step-mother and prove himself a man. He has to pass through fantastical environments that shift like dreamscapes, learn lessons about the transition to adulthood and responsibility, and make a choice between staying in this dreamworld or returning to his mundane reality. Sound familiar?” — from Aren’s review (also seen by Anders)

Ferrari (dir. Michael Mann)

A engrossing portrait of the Italian car magnate and racing titan, Enzo Ferrari, played by Adam Driver is an operatic performance that is fascinating precisely because it veers away from naturalism. Director Michael Mann gets to dig into some familiar obsessions here, namely the monomaniacal focus of the professional man and the personal sacrifices of vocational greatness, so fans of the director will be thoroughly amused. But the story itself is equally compelling as it treats Ferrari’s racing obsessions as seriously as his messy domestic life, including relationships with his aggrieved wife (Penelope Cruz) and younger lover (Shailene Woodley). — Aren

The Holdovers (dir. Alexander Payne)

“An early 1970s setting, a cozy boarding school over Christmas, snowfall and talk of classical civilizations, Cat Stevens songs and cinematography that recreates film grain. The Holdovers has all the hallmarks of a film made for me. That is, aside from the fact that it’s made by Alexander Payne, a filmmaker who has never made a film I’ve loved. Payne has made some good films, namely Sideways (also starring Paul Giamatti) and Election, but even those films are held back by something approaching contempt for his characters. Well, I now have to amend my thoughts as The Holdovers bowled me over. It’s a small film, but not slight, moving, but not sentimental, and like a Hal Ashby picture made in 2023 without the 1970s style or characterizations or structure feeling like a gimmick. And most crucially, it is deeply invested in the characters at its centre.” — from Aren’s review

The Killer (dir. David Fincher)

“Like its meticulous assassin in a bucket hat, The Killer knows all the rules but appears unassuming. Yet, for a film so wedded to the conventions of a subgenre, in this case the hitman movie, why does The Killer feel different?” — discussed by Anders, Anton & Aren on Episode 36 of 3 Brothers Filmcast

Killers of the Flower Moon (dir. Martin Scorsese)

Martin Scorsese’s telling of the murder of members of the Osage nation in 1920s Oklahoma, in order to facilitate the theft of their new found oil wealth, is epic-lengthed and elegiacally-paced. But rather than its nearly four hours being a dutiful slog, it is an attempt to reckon with the nature of guilt and the way that the human heart can hold conflicting emotions within it. Anchored in the performances of Lily Gladstone and Leonardo DiCaprio, Killers of the Flower Moon is more a tragic love story and indictment of human greed than a police procedural, since it is plain to all viewers who are committing the murders. The film sheds light on a key event in early twentieth-century American history without feeling like a lecture. Instead it is an invitation to the act of confession that might precede reconciliation and forgiveness. — Anders (also seen by Aren)

Master Gardener (dir. Paul Schrader)

“During an early scene in Paul Schrader’s Master Gardener, Joel Edgerton’s titular gardener Narvel Roth gives a lesson on soil quality to some apprentices at Gracewood Gardens. As he describes loam and other high-quality soils, he encourages his apprentices to take off their gloves, grab a handful of dirt, and smell it. Not only smell it, but breathe it in and even kiss it. The other apprentices shoot knowing looks at each other, sniggering, but Narvel is deadly serious. He loves the dirt, loves its earthy smell, its feel on his hands, and, yes, the taste on his lips. He wants others to experience that feeling too. But only by allowing themselves to be awkward in the moment can gardeners appreciate the dirt on a deeper level. Master Gardener asks a similar trust of its viewers. It is an arch, often stilted, occasionally even awkward film about a reformed man and the possibilities of grace. And only by surrendering to its particular rhythms—only if we truly stick our faces into the dirt and breathe in and taste its earthiness—can its poetic, even beautifully optimistic, effect be fully appreciated.” — from Aren’s review

May December (dir. Todd Haynes)

Todd Haynes once again puts on his melodrama hat for this interrogation of performance and the unknowability of relationships. He borrows heavily from some tabloid stories of the 90s to tell the story of an older woman (Julianne Moore) who married the younger man (Charles Melton) she statutory raped as an adolescent. The scandal and intrigue of this relationship creates the melodramatic core of the film, but it’s Natalie Portman’s presence as an actress playing Moore’s character in an upcoming movie that gives the film its complicated, prickly appeal. Portman is exceptional in the role as she prods the couple, further exploiting the husband in service to her own vanity, giving the film a textual complexity that makes it more than an entertaining tabloid melodrama. — Aren

Oppenheimer (dir. Christopher Nolan)

“With Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan cements his pre-eminent command of genre forms and narrative innovation among contemporary filmmakers. Nolan’s Dunkirk (2017) provides a useful point of comparison to his latest work. As Dunkirk is a war movie but also very much a Christopher Nolan movie, Oppenheimer is a biographical epic that is also distinctly a film by Nolan. The difference is that the characters in Dunkirk are all but nameless, personifying universal facets of man at war, whereas Oppenheimer is concerned with portraying the individual subjectivity of one man, J. Robert Oppenheimer, the theoretical physicist who led the Los Alamos Laboratory, where the first atomic bombs were invented.” — from Anton’s review (also seen by Anders & Aren)

Past Lives (dir. Celine Song)

“‘What's their story?’ What an intriguing framing for the opening. We hear thoughts off camera (almost a chorus), possible explanations for the connections between the three leads, and then the entire movie answers this stranger's prompt. What comes after doesn't quite live up the genius of the opening, but this is a strong debut that almost plays like a mashup of Kieslowski's Blind Chance and Linklater's Before trilogy.” — from Aren’s Letterboxd review

The Multiplex

Air (dir. Ben Affleck)

“What’s an inspirational sports drama look like without the sports? It looks something like Ben Affleck’s Air, his easy going slice of Hollywood hokum that’s a terrific watch, even if it’s all rather weightless. I was a fan of Argo and Air has many of the same qualities. It shares its canny sense for Hollywood storytelling beats and breezy entertainment quality, even if the stakes of Affleck’s Best Picture-winning historical thriller about the Iranian hostage crisis are a bit bigger than the stakes of this movie about sneakers.” — from Aren’s review (also seen by Anders & Anton)

The Creator (dir. Gareth Edwards)

“When watching The Creator, it’s hard not to think about A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001). Both films are about a cynical man who takes care of a young, adorable robotic child and journeys across a futuristic world in order to reunite that child with its mother. It’s also hard not to think of Blade Runner (1982) and how both films constantly ask whether a machine can be a man. It’s hard not to think about Apocalypse Now (1979) and both films’ visions of a man going on a quest into a heart of darkness in Southeast Asia, passing through rice paddies and jungles to find a mysterious figure who seems to control the fate of the world. It’s even hard not to think of Neon Genesis: Evangelion (1995) in both works’ beautiful, haunting images of angelic beings in the sky and beams of destruction raining down from the heavens. It’s hard not to think of a lot of great works of science fiction when watching The Creator, which speaks to the film’s familiarity despite it not being based on any existing IP.” — from Aren’s review

Creed III (dir. Michael B. Jordan)

“Hollywood has never stopped making movies about men, but very few movies today ask what makes a man. The Creed series is an exception. These Rocky spinoffs about Adonis Creed (Michael B. Jordan), the son of Rocky’s rival turned best friend, Apollo Creed, are explicitly interested in masculinity and the makings of a good man. The first film investigates how to be a good son, the second how to be a good father, and the latest film, Creed III, directed by Michael B. Jordan in his directorial debut, is about how to be a good friend. People come to the film to watch the intense boxing scenes, but they stay to see one of the few portraits of positive masculinity that Hollywood has left.” — from Aren’s review (also seen by Anders)

Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves (dir. John Francis Daley & Jonathan Goldstein)

“I’m in danger of overrating this movie, but I had a blast with Dungeons & Dragons and wish that more movies were as competently made and generally easygoing and fun. Seeing as the film came from Jonathan Goldstein and John Francis Daley, who made the minor comedy classic Game Night back in 2018, I’m not surprised it ended up good. But when compared to the previous adaptation of Dungeons & Dragons, as well as most fantasy movies over the past decade, the film being a success is almost a minor miracle. Would you agree?” — from Anders and Aren’s table talk discussion

Godzilla Minus One (dir. Takashi Yamazaki)

“Who would have known that one of the most emotionally satisfying dramas of 2023 would happen to feature Godzilla in it? But such is the case with Takashi Yamazaki’s Godzilla Minus One, the latest Godzilla feature from Toho Studios and perhaps the closest in spirit and tone to Ishiro Honda’s 1954 original. This is a smartly written and well performed picture with recognizably human themes and satisfying action sequences. Usually, the monster is the main focus in a kaiju picture and the humans are mostly an afterthought, but in Godzilla Minus One, the domestic scenes are as interesting as the disaster ones. The film aces the conventions of the postwar melodrama as well as the disaster picture, making it one of the more pleasant surprises of the past moviegoing year.” — from Aren’s review

A Haunting in Venice (dir. Kenneth Branagh)

“A Haunting in Venice takes advantage of its atmospheric setting in the orphanage, especially once a storm hits and the guests are unable to leave by boat. We get creepy passages, lighting and thunder, and jumpscares aplenty. Poirot himself finds his own sanity pressed by the setting and his past traumatic experiences.” — discussed by Anders, Anton & Aren on Episode 34 of 3 Brothers Filmcast

John Wick: Chapter 4 (dir. Chad Stahelski)

“Near the climax of John Wick: Chapter 4, Keanu Reeves’ titular assassin fights his way up the 222 steps of the rue Foyatier on the way to Sacré-Coeur in Paris. Just as he gets to the top, Chidi (Marko Zaror), the right-hand man of the film’s villain, the Marquis de Gramont (Bill Skarsgård), kicks John Wick and we watch him roll back down the 222 steps all the way to the bottom. Beaten, bruised, but refusing to give up, John gets back up and fights his way up to the top once again, this time with the help of some new allies. This climactic sequence sums up the entire approach of John Wick: Chapter 4, a Sisyphean action epic that is as much endurance test as spectacle.” — from Aren’s review (also seen by Anders & Anton)

Knock at the Cabin (dir. M. Night Shyamalan)

“Few filmmakers working in mainstream American movies are as willing to pursue an out-there idea to its fullness and final conclusion, or to restrain their formal approach to such a prolonged degree. Of course, on both points, we could easily point to a more daring idea and a more formalist technique, but who is doing both as consistently as part of a filmmaking program, while at the same time trying to reach mainstream audiences?” — discussed by Anders, Anton & Aren on Episode 27 of 3 Brothers Filmcast

Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One (dir. Christopher McQuarrie)

“Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One hinges on three exceptional action sequences that see Tom Cruise pull off impressive stunts in exotic destinations around the world. It provides the sort of four-quadrant, big budget fun that audiences expect during the summer movie season.” — from Aren’s review (also seen by Anders & Anton)

Plane (dir. Jean-François Richet)

“It’s all about the simple things in life: a cold beer on a hot day; a comfy chair and a good book; Gerard Butler as a commercial airline captain stranded on a rebel island in the Philippines saying “They’re my passengers, my responsibility.” Jean-François Richet’s Plane is a simple movie, but it understands the pleasures of such a conventional approach to action storytelling. It has patience, clarity, and precision to its storytelling, which plays like a breath of fresh air when compared to the overlong and overcomplicated franchise fare of contemporary cinema. The minimalist, literal title says it all and epitomizes just what a crowd-pleasing, relatively serious and no-frills affair Plane is. It gives you what it promises and doesn’t waste time doing so.” — from Aren’s review

Scream VI (dir. Matt Bettinelli-Olpin & Tyler Gillett)

“Just like all the films in the Scream series, this latest entry is movie-obsessed and self-aware, interrogating the “rules” and conventions of horror films, especially teen slashers and horror franchises, even as it engages in them. The fictional movie series within the series, Stab, allows for characters to reflect directly on movie conventions and the nature of horror fan culture. As a “sequel to the requel,” characters note that the rules are increasingly out-the-window, with legacy characters and even main characters potential targets or suspects, even if the movie ultimately may not go through with those violations.” — discussed by Anders, Anton & Aren on Episode 28 of 3 Brothers Filmcast

Sound of Freedom (dir. Alejandro Monteverde)

“Sound of Freedom is surprisingly formally understated and controlled. The movie is all the more powerful and disturbing for its restraint and focus. What those who complain about the muted tone get wrong is that director Alejandro Monteverde and his crew seem to be consciously avoiding making this an exploitation flick.” — from Anton’s essay “The Images and the Darkness” (also seen by Aren)

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (dir. Joaquim Dos Santos, Justin K. Thompson & Kemp Powers)

“I was primed to feel it was overhyped given the initial responses when it came out, but of all the summer blockbusters and franchise films this one has stuck with me the most and remains one of my favourite films of the year. It feels like a refinement and development of what the filmmakers did with the first one, offering the occasional moment of thoughtful and touching respite to go with the eye-popping visuals. Also, few animated films (outside of Ghibli, naturally) have such a unique and confident sense of style and stick their landing. Even the cliff-hanger ending offered excitement and anticipation rather than a sense of dutiful extension.” — Anders (also seen by Aren)

The Arthouse

BlackBerry (dir. Matt Johnson)

“BlackBerry is the sort of film that has the veneer of a spoof. It stars popular comedic actors, Jay Baruchel and Glenn Howerton. It’s written and directed by and co-starring Canadian indie filmmaker Matt Johnson, who’s best known for his mockumentary Operation Avalanche. It has garish haircuts (or bald caps), funny period references to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Mats Sundin, and a faux verite visual approach, with quick edits featuring a variety of camera angles, and a perpetually moving, handheld camera. It tells a tech origin story, which is basically a narrative formula at this point, about the first smartphone, made by Canadian nerds in Waterloo, Ontario. In bite-size form, BlackBerry could easily be played as an SNL video spoof, but it’s not. The sardonic elements of the film breathe new life into the film’s conventional plotting, which acts almost as a comic riff on The Social Network without the broader social commentary. It lets us see these conventions in new ways, and, more importantly, disarms us for how gripping this story actually is. It’s a rollicking, self-aware, gutsy good time and a thrilling tech procedural.” — from Aren’s review (also seen by Anders & Anton)

Godland (dir. Hlynur Pálmason)

“‘It’s terribly beautiful.’ ‘Yes, it’s terrible. And beautiful.’ This exchange between two lovers late in Hlynur Pálmason’s Godland encapsulates so much of this beguiling, beautiful film that pits man against nature and Denmark against Iceland. It’s a film haunted by the power of nature, which takes the form of the breathtaking landscape of Iceland in the height of summer, when the sun never sets, but snow, rain, and howling winds are possible at all times of day. It’s impossible to visit Iceland without being awed and a little terrified of its barren landscape of waterfalls, windswept grasslands, black-sand beaches, and volcanoes along the horizon. These lines and this film speak to that terrible beauty.” — from Aren’s review

How to Blow Up a Pipeline (dir. Daniel Goldhaber)

“One might be forgiven for expecting Daniel Goldhaber’s film How to Blow Up a Pipeline to be a didactic work of political agitprop. But thankfully the film is instead a suspenseful and thought-provoking treatment of the current political landscape. Taking its title and central ideas from Andreas Malm’s nonfiction work of eco-theory, How to Blow Up a Pipeline, the film is the story of eight individuals, from various backgrounds and motivations, who come together to commit an act of politically-motivated property destruction. Put more bluntly, the film follows eight collaborators as they prepare to blow up a pipeline in West Texas. Revealing their motivations sequentially in flashback, the film deftly portrays the various circumstances that led each of the participants to this act of political violence, or what the characters themselves ultimately admit is eco-terrorism.” — from Anders’ review (also seen by Aren)

The Maiden (dir. Graham Foy)

“Some dreams are so vivid and so tactile that you swear you lived them despite knowing they’re not real. That’s what it feels like to watch Graham Foy’s The Maiden, his remarkable Canadian indie about teenage friends dealing with grief and wandering the ravines and backroads on the edge of Calgary, AB. The film is the sort of feature debut that is all too rare these days and all the more remarkable for it. It’s captivating and intuitive as it moves to its own rhythm and defines its own style. — from Aren’s review

Skinamarink (dir. Kyle Edward Ball)

“You know the fable about the frog and the boiling water? Well, that’s how Skinamarink works. Its avant-garde approach lulls you to sleep so that you wake up in a nightmare.” — from Aren’s review (also seen by Anders)

Suzume (dir. Makoto Shinkai)

“Makoto Shinkai’s Suzume is defined by three striking, beautifully animated visuals. One is an abandoned door frame that leads to a magical, purple-tinted grove with a billion stars lighting up the night sky. Another is a child’s wooden chair with a missing leg, unable to stand unless propped up against a stable surface. The third is a massive, spectral red worm burrowing out of a hillside and looming over a coastal city like a tempest.” — from Aren’s review (also seen by Anders)

You Hurt My Feelings (dir. Nicole Holofcener)

“The sort of dependably funny, fairly wise, visually bland adult romcom that Woody Allen used to put out once a year. Nice to watch films like this that understand their small stakes and act accordingly. Also great to watch a film about marriage that doesn't make cheating a big part of the narrative.” — from Aren’s Letterboxd review

The Hot Doc

The Castle (dir. Martín Benchimol)

“The Castle is an observational documentary with humour so dry it could evaporate the wet mist that drapes the walls of the decaying manor house at the film’s centre. Martín Benchimol’s 78-minute film is quiet and patient and brims with atmosphere. Part of the evocative atmosphere is provided by the strange location, a massive mansion in the Argentine countryside with holes in the roof and shoddy plumbing. Part of it is also provided by Benchimol’s stylized presentation of the material. He employs a deft touch with moody lighting, ironic editing, and a completely hands-off approach to the material. You never see or hear the film crew. Rather, you simply watch these strange people in this massive house right out of a fairy tale and marvel at the lowkey, oddball energy of the situation.” — from Aren’s review

Food and Country (dir. Laura Gabbert)

“Director Laura Gabbert’s Food and Country offers a wide-ranging look at the ongoing crisis in American food production. The film follows food writer and former restaurant critic for both the Los Angeles and New York Times, Ruth Reichl, as she interviews people at all levels of the food production chain, from farmers to restaurant-operators, ostensibly about the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic had on food production. The film uses one highly visible crisis to explore aspects of another neglected and long unfolding one. Through its historical approach and the variety of subjects it interviews, Food and Country reveals the relationship between North America’s love of cheap food and a myriad of other socio-political effects.” — from Anders’ review

The Longest Goodbye (dir. Ido Mizrahy)

“Space travel is hard on the body and the mind, but the former has garnered far more attention in the history of space travel than the latter. The Longest Goodbye explores NASA’s institutional attempts to rectify this imbalance, examining the psychological toll that will come as humans venture deeper into space. If NASA is to ever send humans to Mars—which they say they are planning to do in the coming decades—then those astronauts will have to spend over three years away from Earth and, more importantly, their families and friends. Dr. Al Holland has been tasked with spearheading the psychological preparation and debriefing of astronauts in their space program. Ido Mizrahy’s The Longest Goodbye explores Dr. Holland’s role at NASA as well as the broader questions raised by his work.” — from Aren’s review

The Rise of Wagner (dir. Benoît Bringer)

“The atrocities committed in Russia’s war in Ukraine have put the paramilitary organization Wagner Group on the front page of countless newspapers worldwide, but this private army was active long before tanks rolled across the Ukrainian border. Benoît Bringer’s The Rise of Wagner documents the history of this organization, from its beginnings in the civil war in Syria to its present day work in Ukraine and for dictators and mining companies across Africa. It’s a sobering film about the prevalence of violence in our modern world and the ways that the Russian state acts as a shield for the organization, despite denying its very existence.” — from Aren’s review

Scala (dir. Ananta Thitanat)

“It’s almost impossible to imagine that Ananta Thitanat hasn’t seen Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn, the Taiwanese master’s acclaimed 2003 ghost story about an old theatre closing down with a final showing of King Hu’s wuxia epic, Dragon Inn. Thitanat’s slow cinema documentary Scala takes a cue from Tsai’s film in documenting the dismantling of the Scala theatre in Bangkok, the city’s last arthouse theatre and the final bastion of an erstwhile cinema culture. Now all that remains in Thailand are multiplexes, so the Scala’s destruction is the end of an era.” — from Aren’s review

Total Trust (dir. Zhang Jialing)

“Imagine you need to take your child to school, but when you look out the pinhole camera on your front door, a mysterious woman stands watch from a shadowy doorway outside. When you open the door, four other people appear and block your way. They tell you you can’t leave. They don’t explain who they are, but they don’t allow you to move and they threaten action if you do. You retreat inside and as you try to watch what they’re doing, they come up to your door and put tape over your camera so you’re left blind and trapped. This is an actual scenario that occurs to a family in Zhang Jialing’s Total Trust, a documentary about the oppressive surveillance regime that paralyzes dissidents in China.” — from Aren’s review

The brothers discuss how Avatar: Fire and Ash functions as a planetary romance, Cameron’s use of repetition, and the film’s themes and character development.