Aren's Top 10 Films of 2021

1. Dune (dir. Denis Villeneuve)

When a film transports me—overwhelms me—to the degree that Denis Villeneuve’s Dune does, I know I have a new favourite. After seeing it for the first time (I’ve seen it six times so far), I mentioned jokingly to my wife that it was my new favourite movie of all time. But I have to wonder how much I was joking. Frank Herbert’s novel is my favourite novel. I’ve made no secret of this in roundtables and on podcast episodes. But it’s not just that Villeneuve’s film adapts the first two-thirds of my favourite novel. It’s that it adapts the novel well and makes it something unique to the cinema. In short, this is a movie that captures so much of what I love about movies.

Start with the visuals. The scale of this film is overwhelming. The shots of titanic spaceships silently lifting off from planets; the enormous sandworm swallowing a spice harvester; the visions of a future holy war; and the recurring images of Chani (Zendaya) calling Paul (Timothée Chalomet) to the sands of Arrakis—these are disarming visions of strangeness, showing how this world is alien from our own. And yet, the visuals are also familiar. There are human emotions on screen, human conflicts, and insight into personal struggles and existential awakenings, whether the image of a mother holding back tears for her son or the frown on a father’s face over his son’s increasing emotional distance. It offers a vision of the sublime, but one that is anchored by authentic portraits of humanity, specifically Paul’s terrifying realization of what he does and does not control in his life and the world around him. We read about these things in the novel, but Villeneuve transports them to the screen in ways that are unique to the movies: with a scale, colour, and intimacy that visualizes abstract concepts in concrete ways.

The music amplifies both the disarming visuals and the quiet emotions. Hans Zimmer layers musical tones and weaves together vocals and ambience in ways I’ve never heard before. Listening to it is like eavesdropping on a message from another world. It’s a major addition that isn’t possible in the novel, adding an aural dimension that immerses us further in this world. The storytelling, which streamlines the novel, combines the Hero’s Journey with an investigation into the moral cost of messianism. It interrogates how religion and politics work together and apart to shape societies. It challenges the notions of destiny that are found in so many stories of this sort. It’s a film that plays into conventions while also deepening the engagement with these conventions, not satisfied to simply use an archetype, but to question it. Think about Paul’s vision of a future holy war, which shows that his defeat of the Harkonnens would lead to untold destruction and ruin across the galaxy; this isn’t how most Hero’s Journeys end. Dune is not a subversive film, but you won’t find a more critical use of archetypes in popular entertainment.

Ultimately, it’s the film’s ability to transport me to another world that I cherish most. I know movies are not real, but when I watch a movie like Dune, I forget that fact and am able to live another life for a few hours. It’s magical.

2. Can’t Get You Out of My Head: An Emotional History of the Modern World (dir. Adam Curtis)

Adam Curtis’s six-part, eight-hour documentary about the malaise and frustration of our modern world is the film that captured the feeling of 2021 better than any other. Things simply do not work well in our modern political and economic systems and we feel powerless to change them. Curtis’s film is a sobering and yet ultimately hopeful reminder that things don’t need to be this way. Curtis, in his now-famous collage style, which uses only archival footage from the BBC, jumps around the 20th and early 21st century to link together the stories of key radicals, including Jiang Qing (also known as Madame Mao), Michael X, and Afeni Shakur (Tupaq’s mother). The film was born out of Curtis’s desire to investigate how the liberal world had failed to see Brexit and the election of Donald Trump coming, and to explain why it failed to adequately respond to those events. Now, in the light of the pandemic, the consolidation of world capital, and the oncoming climate catastrophe, the film’s investigation is more relevant than ever. There are killer needle drops, ironic juxtapositions of sound and image, and stunning bits of archival footage put to startling purpose, but the film is most impressive for how Curtis is able to chart the origins of our emotional moment and make sense of the chaos. Decades from now, when future human beings are trying to understand the emotional experience of living in 2021, they can turn to Can’t Get You Out of My Head for a record of this time.

3. The Card Counter (dir. Paul Schrader)

Paul Schrader is something of an old dog in Hollywood, but The Card Counter is hardly a new trick, as it’s another in his long line of films about “God’s lonely men”—men who are filled with guilt and anguish and think redemption is only attainable through suffering and violence. At the same time, The Card Counter is no empty repetition. It’s not simply a personal story of guilt and despair. It makes the personal political, even on a national scale, as it dovetails Bill Tell’s (Oscar Isaac) story of guilt with the national guilt of America in the War on Terror. Oscar Isaac gives one of his best performances here, which is saying something, and the film’s exploration of penance through the isolation and routine of professional gambling is remarkably perceptive. The Card Counter is brutal in its content—the flashbacks to Abu Ghraib are visions of hell—but it also offers a sliver of hope and a vision of what grace can look like to cut through our deepest despair.

4. West Side Story (dir. Steven Spielberg)

When I first heard that Steven Spielberg was remaking West Side Story, I thought it was unnecessary. I was wrong, because although it’s not a matter of this film improving on Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins’ 1961 Oscar-winning version—which I still think is better—it’s that this is a great movie in its own right, with tantalizing musical sequences and some of the most gorgeous cinematography of recent years. Watching Spielberg’s version is not about watching an improvement on the original (I like the authenticity of much of the casting and the use of Spanish, although I would’ve preferred subtitles during key scenes), but about watching Spielberg—possibly the most talented filmmaker to ever live—move a camera and bring to life one of America’s great musicals with passion and verve. This is a beautiful film that reminds us of the possibilities of the musical genre.

5. The Beatles: Get Back (dir. Peter Jackson)

Like Can’t Get You Out of My Head, The Beatles: Get Back may be considered television for some people, but I see it as a three-part movie, one that is an insightful and easygoing look at how art is made and what the creative process looks like. The fact that Get Back is split into three parts allows Jackson to take his sweet time with the footage—and what remarkable footage this is! Over the eight hours, you get to witness the act of creation (Paul ripping “Get Back” from the ether while simply strumming on his bass guitar is mindblowing), personal encounters between Paul McCartney and John Lennon that we had only dreamed about (such as the audio recording of their lunchroom chat), and astounding performances, including the entire rooftop concert at Apple Studios. In many ways, the film functions as a counter-narrative to the popular conception of how the Beatles broke up. It makes it so clear that these four men worked well together and inspired each other’s creativity and brilliance, even if their personalities brushed up against each others’. But it is most illuminating as a hangout film and a look at how art is made. Few movies capture the act of creativity in such detail because its length allows us to see that creativity is a process, not an act.

6. Drive My Car (dir. Ryusuke Hamaguchi)

Most years, there’s at least one patient international drama that stuns me (and much of the film community). This year, that film is Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car, an adaptation of some works by Haruki Murakami, which stars Hidetoshi Nishijima as Yusuku Kafuku, a theatrical director and actor who puts on a performance of Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya in Hiroshima. Over the course of the film, we watch his interactions with the cast and crew, his interpretation of the Chekhov play, and his blossoming friendship with his quiet driver, Misaki Watari (Toko Miura). Drive My Car is slow—it takes 45 minutes for the opening credits to play. It is quiet—characters hardly raise their voices and most emotions are bottled up inside, though plainly visible on characters’ faces. And it is achingly perceptive about how we process pain and loss and missed opportunities. Most importantly, it shows how the creation of and engagement with art finds a way to shape and provide meaning for our lives.

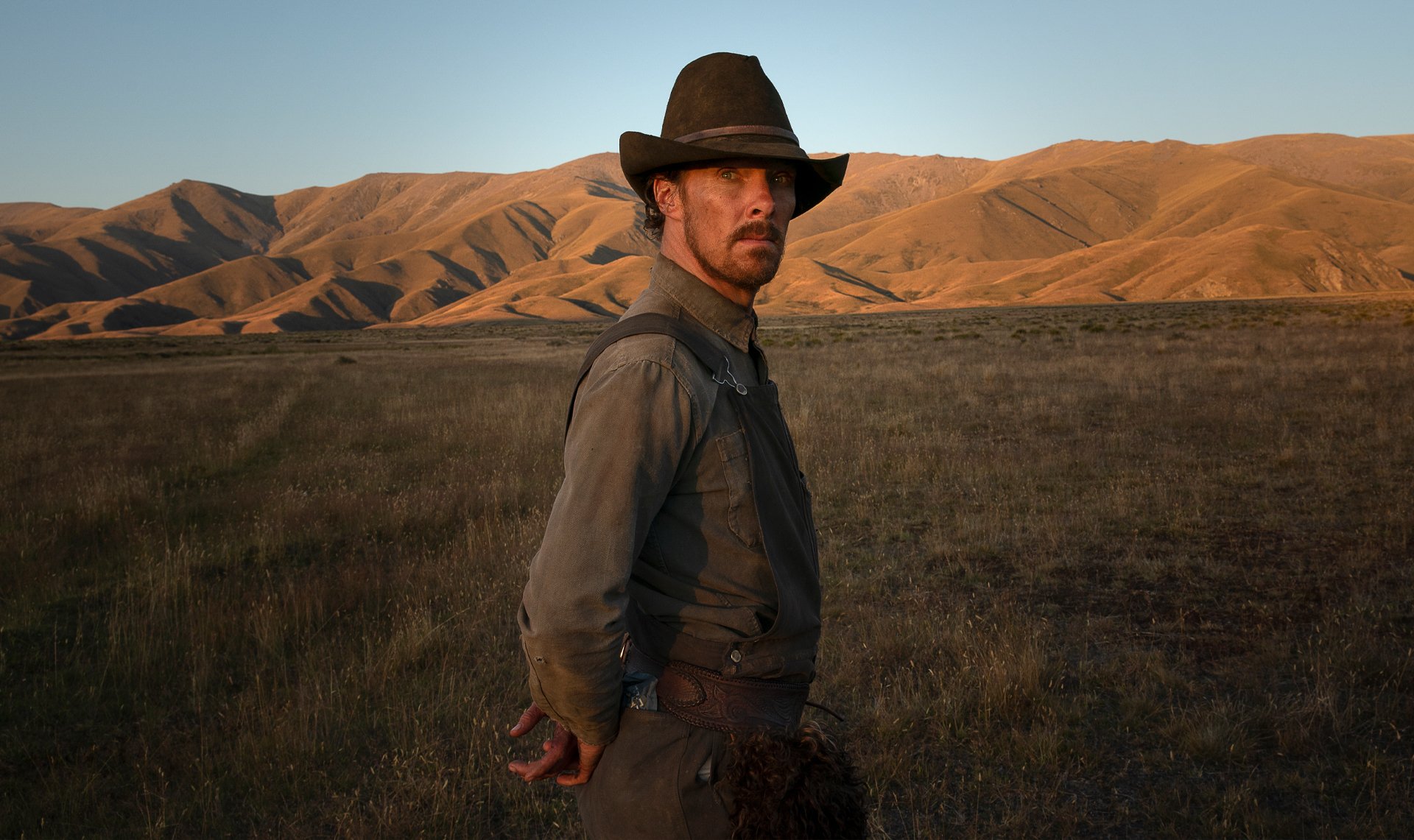

7. The Power of the Dog (dir. Jane Campion)

On the surface, The Power of the Dog is subversive and topical. It examines a rotten individual—Benedict Cumberbatch’s cowboy, Phil Burbank—and uses him to comment on the Western genre and masculinity as a whole. But the film is not simple or reductive in my mind. Rather, the film is a fascinating examination of power dynamics and idolatry in the American West. Through Phil and his relationships with his brother, George (Jesse Plemons), George’s wife, Rose (Kirsten Dunst), and Rose’s son, Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee), we come to startling realizations about manhood and power and agency and how we shape ourselves as individuals. But The Power of the Dog is not simply a high-minded arthouse film with impenetrable storytelling. It’s an entertaining drama, with a tense narrative, surprising twists, wonderful acting, and some sharp filmmaking behind the camera. Jane Campion has crafted a thoughtful and challenging variation on the traditional Western picture.

8. Zack Snyder’s Justice League (dir. Zack Snyder)

Zack Snyder’s Justice League is something of a miracle. I’m shocked that Warner Bros. actually allowed Snyder to re-edit the project four years after its initial release and to film new footage for it. I’m even more shocked by how well it turned out. Instead of being slapdash and stitched together, Zack Snyder’s Justice League is epic and patient and cathartic. It is a work of deliberate and confident artistry in the most popular storytelling format of our day and age: the superhero movie. It patiently sets up the relationships between its band of heroes, demonstrates the stakes of the conflict, and builds to a conclusion that satisfies the narrative while also offering emotional catharsis for the characters. For superhero pictures, it doesn’t get much better than this. We should probably place a moratorium on superhero epics at this point, since most will feel redundant in the wake of Snyder’s film.

9. Licorice Pizza (dir. Paul Thomas Anderson)

The other hangout picture on this list is a truly plotless film in the vein of Robert Altman, which delights in the colours, sounds, and, most of all, emotions of the 1970s. Paul Thomas Anderson’s ode to his childhood, which charts the friendship and kinda-sorta romance between a teenager (Cooper Hoffman) and a young woman in her twenties (Alana Haim) is a film that is genuinely nostalgic. So much of the pleasure of this film is in the period detail: the squishy surface of a waterbed; the warm tones of its soundtrack of great 1970s songs; the texture of 35mm film grain. Licorice Pizza captures the joy and pain that comes with nostalgia, as well as the clarity of understanding that comes with time. The film clearly has such affection for this time and place, but is not blind to the era’s shortcoming, nor does it erase the confusion and hesitation that undergirds the film’s central relationship. That’s why it’s not an exercise in empty nostalgia. It embodies the conflicted nature of nostalgia: that by luxuriating in the past, we open ourselves up to its pain and the haunting presence of unanswered questions and unacted upon opportunities.

10. The Last Duel (dir. Ridley Scott)

Ridley Scott’s medieval drama bombed at the box office, but disabuse yourself of the notion that The Last Duel is a failure. Written by Matt Damon, Ben Affleck, and Nicole Holofcener, it’s essentially Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon set in 14th-century France. It tells the story of the rivalry between two knights, Jean de Carrouges (Damon) and Jacques Le Gris (Adam Driver), and the rape of Jean’s wife, Marguerite (Jodie Comer), over three chapters that repeat the narrative events from each character’s point of view. First we watch Jean’s version of events, then Jacques’, then Marguerite’s. While the film clearly favours Marguerite’s version of events as the closest to the truth, the triptych structure perceptively shows how different people understand the stories of their lives in different ways. It’s not so much an investigation of the slippery nature of truth, but rather the different ways that events can be experienced depending on personality, class, and, most importantly, sex. Furthermore, the film is surprisingly entertaining, with exciting battle sequences, including its climactic duel, gorgeous production design, and a wealth of humour that you wouldn’t expect in a film with this subject matter (Ben Affleck is a hoot). In a year with several noteworthy films taking place in the Middle Ages (including The Green Knight and The Tragedy of Macbeth), it’s the best of the bunch, not only for allowing us to understand what our modern time shares with the medieval world, but also through the startling clarity of its presentation. It deserves to be remembered.

Another 5

Annette (dir. Leos Carax)

The Green Knight (dir. David Lowery)

Riders of Justice (dir. Anders Thomas Jensen)

Spencer (dir. Pablo Larraín)

The Tragedy of Macbeth (dir. Joel Coen)

The brothers discuss how Avatar: Fire and Ash functions as a planetary romance, Cameron’s use of repetition, and the film’s themes and character development.