The First 45 Minutes of Independence Day (1996) Epitomize Its Brilliance

What a marvel of popcorn filmmaking Roland Emmerich’s Independence Day remains 25 years after its release! Sure, the film has a reputation for embodying cornball, earnest, raw-raw American excess. However, while the film is certainly corny and earnestly American—how could it not be with its title—it also captures the joyous emotion and spectacle of big-budget Hollywood filmmaking at its best. (It’s perhaps ironic that a German national made the definitive film about American exceptionalism.) T2: Judgment Day and Jurassic Park are better films, but they also transcend the decade in which they were made due to the obsessions and stylistic influences of their master directors, James Cameron and Steven Spielberg. Roland Emmerich, no matter how skilled a technician and entertainer he is, is not on the level of Cameron or Spielberg, but he does direct perhaps the most effective piece of 1990s blockbuster filmmaking outside of their films.

Much of the film’s success is a result of its brilliant use of a well-known conception and a conventional narrative structure. The appeal of the film hinges on that very premise: what would happen if giant flying saucers descended over the major cities in the world? How would people react and what would the alien ships do? It moves the various pieces into place with this fantastic premise while introducing its diverse cast of characters. It then raises the stakes to apocalyptic proportions before resolving the global crisis and personal conflicts in a cathartic manner. This construction isn’t rocket science, but rather a savvy demonstration of the effectiveness of the three-act Hollywood structure.

The first 45 minutes of the film effectively mine the dramatic tension and mystery of its central premise: what would happen if alien ships arrived on Earth in the 1990s? Following a shot of a shadow falling on the Apollo landing site on the Moon, a S.E.T.I. operator picks up radio signals from space and calls his superiors to tell them that he’s getting signs of a genuine extraterrestrial presence. Something is coming, but we don’t yet know what that coming portends. Will these visitors be benevolent or malicious? The film’s iconic trailers may have answered this question before the film’s release, but Emmerich and his co-writer, Dan Devlin, don’t tip their hand within the film itself, leaving open the possibility of a peaceful encounter in the manner of Close Encounters of the Third Kind. It’s only later that the film explicitly operates as a counter to Spielberg’s UFO classic, even mocking the sound-and-light show of the climax of Spielberg’s film with the “welcome wagon” helicopter that’s easily destroyed by the aliens. Until that time, it lets the tension build in an almost Hitchcockian sense, amplifying our own sense of unease the closer we get to the moment of reveal.

The film then jumps around the country introducing the key figures in the story and setting up their emotional motivations and personal travails, which will inform later parts of the film. Most of the focus is on the three core heroes: President Whitmore (Bill Pullman), a Gulf War veteran who has lost national confidence due to his relative youth, but who we observe to be a loving husband and father; Air Force pilot Steven Hiller (Will Smith), who is considering proposing to his stripper girlfriend, Jasmine (Vivica A. Fox), just as he’s about to leave on a mission; and satellite technician, David Levinson (Jeff Goldblum), who picks up the alien signal at the television station where he works and realizes that the cycling binary code indicates a countdown.

These three heroes will eventually come together to save the day, but at the outset they are separated, and as the radio signals become radar signals and eventually 15-mile-wide flying saucers that descend over the major cities in the world, the clock starts to count down. What is so enjoyable about Independence Day in these opening minutes is that it doesn’t restrict the perspective to only the three heroes. It includes a wide range of side characters who are afforded their own mini-arcs or moments of emotional catharsis, whether it’s Jasmine’s friend at the stripclub who wants to greet the aliens, or David’s coworker, Marty, played by Harvey Fierstein, who frets on the phone with his mother and desperately tries to flee the city.

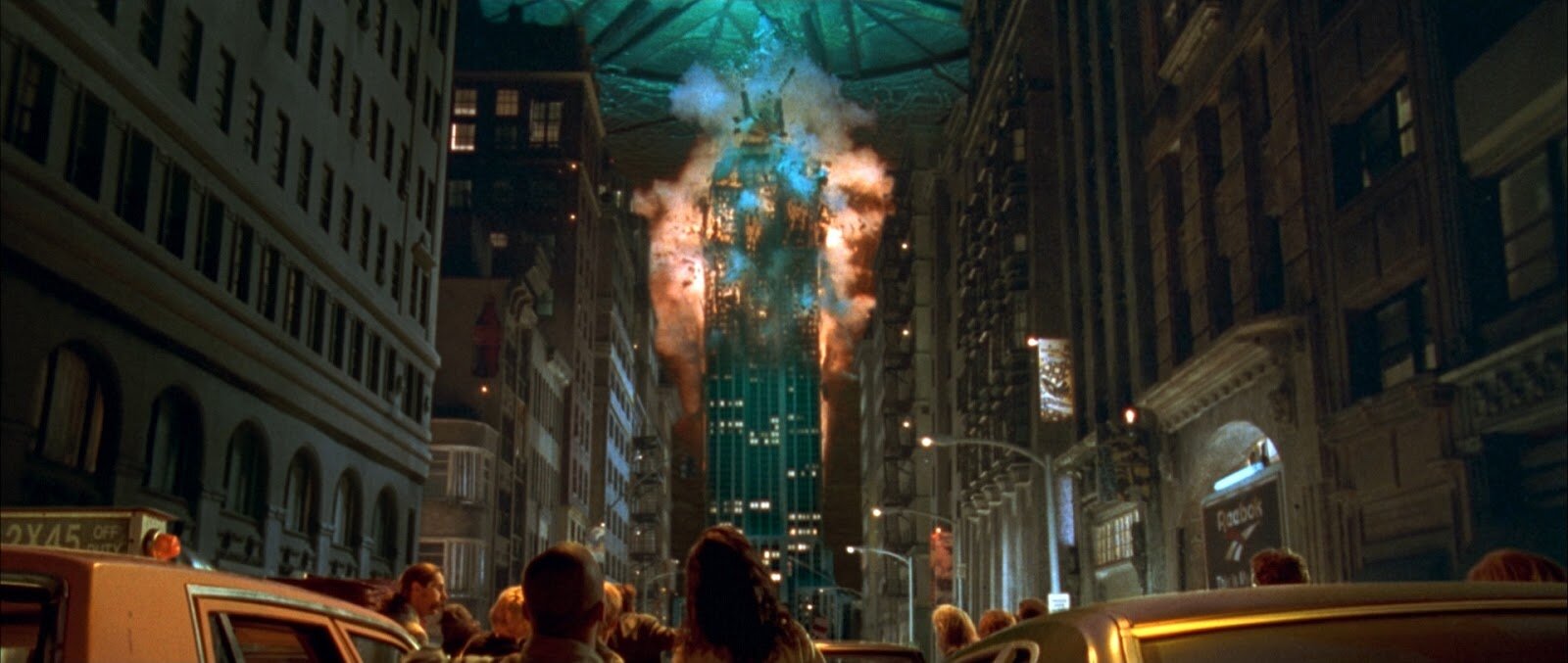

Despite how long blockbusters today are, they don’t allow for these incidental moments of character to pad out a film’s runtime; the screenplays are too viciously economical, paring away anything that doesn’t move the plot forward, explicate the worldbuilding, or expand the viewer’s emotional understanding of the protagonist. In contrast, films of the 1990s like Independence Day are happy to give a segment here or there to side characters who add nothing but flavour and emotional anchors for the audience. These moments are often humorous, as in the case of Marty’s phone conversations with his mom. There’s an earnestness to the humour, which relies on goofiness more than one-liners or quips, which adds a lived-in feel to the world of the film. The characters may be cliches, but they resemble real people. But these moments can also turn tragic, as happens when we see Marty trapped in his car and helpless against the oncoming inferno when the aliens attack the Empire State Building.

The most important of these side characters is Randy Quaid’s Russell Casse, Vietnam vet, alcoholic, hapless father, and alien abductee. The early scenes of Russell set him up as a buffoonish fool, but each moment showing how pathetic he is, whether it’s him drunkenly crop dusting the wrong farmer’s field or being scolded by his son, builds our desire to see the man redeemed. He is a man begging for an opportunity to show himself better than what others think of him, and the film eventually pays off his desire in the climactic aerial dogfight, in which Russell sacrifices himself to destroy the alien vessel. His parting quip, “Hello boys! I’m baaackkk!” as he flies into the saucer’s energy beam, is the sort of goofy one liner that speaks to the cornball nature of Independence Day, but it’s also the sacrifice that pays off all the prior scenes that speaks to the film’s effectiveness. The scenes in the first 45 minutes sow the seeds for the final catharsis. Again, this is simple plot development, but expertly done.

Eventually, the aliens attack and the heroes desperately flee the apocalyptic destruction. Some, like Fierstein’s Marty, are not so lucky, but the core heroes survive and regroup for a counter attack. Emmerich cross-cuts between the characters in the core locations—Los Angeles, New York, Washington—in the moments leading up to the attack, possibly learning from George Lucas about the power of parallel editing to amplify tension and maintain momentum. It’s at this moment where the film proves itself to be the counter to Close Encounters of the Third Kind, as the alien ships power up their energy beams and figures look into the sky in awe, evoking the “Spielberg face” at the visions of otherworldly beauty. But instead of transcendence, the beams bring them death.

The sequence peaks with the shot of the flying saucer destroying the White House, one of the most iconic special effects shots of all time. However, the film might be better epitomized by the miniature sequence of Jasmine fleeing for safety into an underground tunnel with her son, only to call to her faithful golden retriever to outrace the inferno and jump to safety in the nick of time. That shot of the dog jumping through the door as the flames threaten to consume it epitomizes Emmerich as a filmmaker: there is destruction and tension, yes, but also emotional payoff and a construction that promises the effective use of cliche in service of catharsis. No one wants to see a dog die on screen, so the salvation of the dog in the nick of time is the best way to involve the viewer and allow him or her a minor victory in the face of devastation.

The 45-minute opening of Independence Day ranks with the best openings in all of blockbuster cinema. The section is populated with lively actors in memorable roles, mines maximum tension through parallel editing, and crafts and resolves various arcs that are immensely satisfying to audiences. It also has some of the most vivid and effective uses of visual effects in big budget filmmaking. The hour and a half that follows, in which the heroes face further set-backs, discover an occult history at Area 51, and eventually triumph in a last ditch effort to save Earth, is effective in paying off the emotional arcs and narrative conflicts of the first 45 minutes, but it’s this opening sequence that best embodies the effectiveness of the film as a whole. Every narrative construction, editing pattern, or character moment that makes the film a joy to watch is present in these opening 45 minutes. I don’t need to explicate the rest of the film to capture what makes the film so entertaining; it’s all there from the get-go.

There is a giddy pleasure, nay, even pure joy, in watching Independence Day and witnessing how its conventional construction pays off in marvellous ways. Tension and release. Conflict and catharsis. Independence Day weds the fundamental storytelling of Hollywood cinema with the best filmmaking tools and actors money can buy. It is spectacle in the purest definition of the term and about as satisfying a corny blockbuster as has ever been made.

Independence Day (1996, USA)

Directed by Roland Emmerich; written by Dean Devlin and Roland Emmerich; starring Will Smith, Bill Pullman, Jeff Goldblum, Mary McDonnell, Judd Hirsch, Margaret Colin, Randy Quaid, Vivica A. Fox, Robert Loggia, James Rebhorn, Harvey Fierstein, Adam Baldwin, Brent Spiner.

Anton makes the case for watching the first Harry Potter movie during Christmas time.