Introduction to Zack Snyder Retrospective

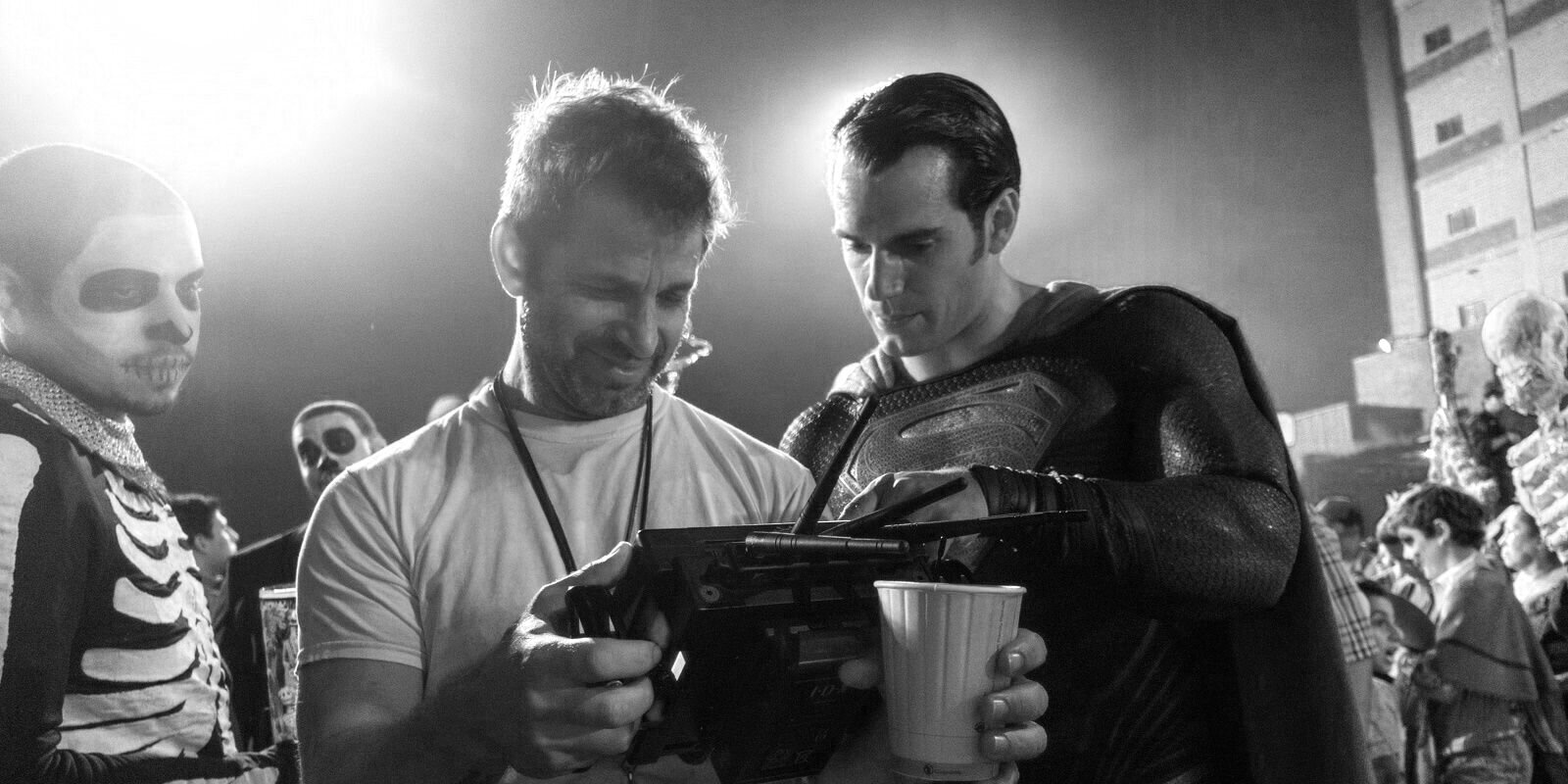

With the long-awaited, grassroots-championed #SnyderCut of Justice League arriving this week and his zombie follow-up, Army of the Dead, on the horizon for May, we are launching our retrospective of the films of Zack Snyder. Known best as a visual stylist and one of the major figures behind the DC Extended Universe, we aim to open up new perspectives on his filmography and his development as a filmmaker, while also addressing his contributions to comic book adaptations and genre filmmaking more broadly.

Zack Snyder arrived on the scene in 2004 with his explosive remake of a genre favourite, Dawn of the Dead. Far from a sophomoric dud, 300 (2006, Snyder’s second directorial effort, remains one of the most famous completely-unforeseen box office smashes, and, with its bold hyper-stylized visual scheme, was lauded at the time as a new kind of comic book adaptation. With Watchmen (2009), Snyder moved on to the superhero genre (of the DC variety), which has dominated his filmmaking ever since, with a few notable exceptions, namely Legend of the Guardians: The Owls of Ga’Hoole (2010) and Sucker Punch (2011).

While those two films had lukewarm critical and commercial receptions, Snyder’s superhero movies have all pulled in powerful box office receipts at the same time that they have divided both fans of the comic books as well as wider audiences. Watchmen has been assailed as both too different from Alan Moore’s work and a stiff, carbon-copy adaptation. Man of Steel (2013) was perhaps most riveting as a teaser trailer, and spawned enormous debate about the destruction, death toll, and length of its climactic, skyscraper-smashing ending. Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016) is easily one of the most gung-ho, batshit crazy, love-it-or-hate-it pop movies out there—although, as Anders and Aren are happy to point out, the critical reappraisals are already happening. And Justice League . . . well, the 120-minute version we currently have isn’t really his movie. So, we wait to see the four-hour cut that showcases Snyder’s personal vision of the material.

One of the justifications for this retrospective is that none of Snyder’s films are boring—and we’re talking on multiple levels. They all are wildly, if sometimes insanely, entertaining, but at the same time they display, as we hope to reveal and explore, varying levels of thematic and intertextual depth and dynamics. Snyder is one of the 21st century’s true pop culture auteurs (“auteur” being meant in the descriptive more than evaluative sense). He is also a keen investigator of the idea of the hero, flawed and mortal, as well as godlike. If, as David Bordwell has argued, Christopher Nolan’s career is marked by a recognizable formal project, involving narrative experimentation in the settings of popular genres, Snyder, one of the other major blockbuster filmmakers of the new millennium, has a career marked by signature stylistic and thematic concerns.

No director is more associated with slow-motion action than Snyder; his name is synonymous with speed-ramped violence set against a cloudy, lightning-speckled sky. He takes the splash panel spectacle of comic books and transfers it onto the screen in tableaux visions of godlike feats. You could argue he’s more responsible for incorporating and popularizing CGI in choreographed on-screen chaos than even Steven Spielberg and Ridley Scott. His breakthrough films emphasized the spectacle in blockbuster filmmaking and set the template for R-rated action and superheroes. Hollywood filmmakers today are still either conforming to or reacting against Snyder’s approach.

Thematically, he is interested in what heroism means in a range of settings, from the zombie apocalypse, to the stylized ancient past, to the realm of superheroes and their status as modern legends and gods. Snyder’s visual interests complement his thematic concerns, as the look, shape, and texture of our heroes is a major signifier of our understanding of them, from Sarah Polley’s blood-stained nurse, to the insane six-packs of his Spartans, to the masked Rorschach, to a Superman ascending Christ-like against a golden sky. His obsession with the moral, physical, and often mortal cost of heroics is consistent across his filmography, from the sacrifice of the Spartans at Thermopylae to Rorschach’s martyrdom to the Man of Steel’s and the Dark Knight’s tortured existences to Superman’s sacrificial defeat of Doomsday.

Although his box office success cements him as one of the most successful contemporary American filmmakers, Snyder remains polarizing with audiences. We know that some of you might be cheering and some of you might be jeering as we launch this retrospective. Know, though, that we are less concerned about making you like or love his works, and more about getting you to think seriously about them. Yes, there is a lot going on within his tableaux shots and CGI renderings—perhaps more than you’ve previously considered—and we hope you’ll join the conversation as we begin to unpack the films of Zack Snyder.

Zack Snyder Retrospective Reviews

Legend of the Guardians: The Owls of Ga’Hoole (2010)

Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016)

Zack Snyder’s Justice League (2021)

The brothers discuss how Avatar: Fire and Ash functions as a planetary romance, Cameron’s use of repetition, and the film’s themes and character development.