Table Talk: Peter Bogdanovich's Targets (1968)

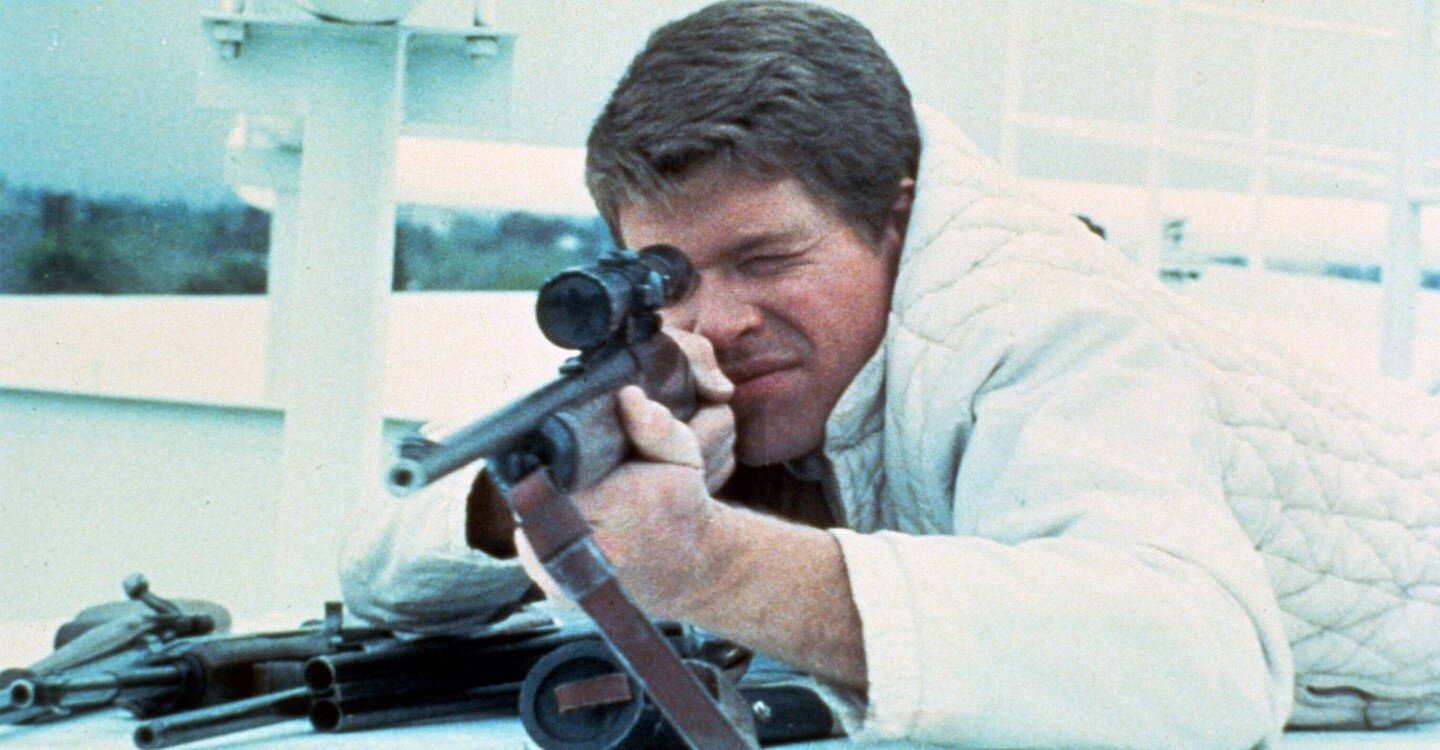

The Criterion Channel recently made available Peter Bogdanovich’s Targets (1968) as part of a “3 Films By Peter Bogdanovich” collection, also including The Last Picture Show (1971) and What’s Up, Doc? (1972). Upon release, Bogdanovich’s B-movie feature debut, which was produced by B-movie mogul Roger Corman, received mildly positive reviews, but critics such as Roger Ebert found its two main plots, one about an aging B-movie star played by Boris Karloff, and another about a sniper played by Tim O’Kelly on a rampage across Los Angeles, to be utterly divorced from each other. However, over 50 years later, it’s really hard not to see how remarkable Targets is, not only as a film that does a lot with a very small budget, but also as a precursor to so many pastiche films to follow, not least of which are the works of Quentin Tarantino.

Connections to Quentin Tarantino and Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood (2019)

Aren: Even if you weren’t aware of how fond Quentin Tarantino is of this film (as we are), I think it’d be very easy to draw comparisons between Targets and his work, especially his most recent film, Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood. For one, they’re both set around the same time period: 1968 and 1969, respectively. They both split their focus between a washed-up actor (Leonardo DiCaprio’s Rick Dalton in Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood and Boris Karloff’s Byron Orlok in Targets) and a violent crime that draws on historical events, Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood being literally about the Manson Murders, while Bogdanovich’s Targets clearly taking inspiration from the University of Texas, Austin shooting of 1966. And the climax of each film has the life of the actor overlap with the life of the real-world killer(s), with the actor intervening and stopping the killer(s) in their tracks, but only through an overlapping of movies with the real world.

Anders: Tarantino’s appreciation of a porous relationship between cinema and reality is probably something that goes beyond even Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood. Consider that the climax of Inglourious Basterds (2009) takes place in a cinema with the image on the screen, Shoshanna as “Angel of Vengeance”, while the Nazis are burned to death with nitrate film stock. But Targets does seem to be a major influence on Hollywood, despite Tarantino saying on a recent podcast that he didn’t realize it until part way through production. Noting the comparison isn’t particularly insightful on its own, but I think that it says something more about what Tarantino believes about cinema and its power. And that power is complicated by the relationship between cinema and violence we’ll get to shortly.

It’s also worth noting a bit of the history of Targets, as a Roger Corman vehicle. Corman often gave young directors assignments where they would get the job, but they would have to recycle portions of earlier Corman works into the new one as a cost saving economic device. What Peter Bogdanovich and his then wife, Polly Platt, did was create a remarkably good story that met the requirement that they incorporate 20 minutes of Corman’s The Terror (1963) into the film. They then used the two days of shooting that Corman still had Boris Karloff under contract for the rest of the scenes. What was meant to be a cost-saving, recycling job becomes integral to the story through the two overlapping plots: the waning career of horror film star, Byron Orlok (Karloff), and the violent saga of Bobby Thompson (Tim O’Kelly).

We can talk about Bobby when we’re talking about the film’s prescience and violence, but I do think Boris Karloff is pretty great here. His self-conscious reflection upon his own status seems genuine and moving, not unsimilar to Rick Dalton by the end of Hollywood, though Orlok has more self-awareness. As he remarks, “They used to say, Garbo makes you cry, Chaplin makes you laugh, Orlok makes you scream. Now, they call my films camp.” Orlok is basically Karloff, and it’s a bold and brave role.

I think the reason Karloff is so good in the film and can embrace its gentle, mocking reflection on his camp status is that the film demonstrates a genuine affection for the actor. Ultimately, Targets affirms the value of classic cinema, no matter its social relevance. I mean, saddled with Corman’s requirement that he use 20 minutes of The Terror (which works additionally on audiences today in providing a young Jack Nicholson cameo!) Bogdanovich goes and adds additional sequences from Howard Hawks’ The Criminal Code (1931)!

In the scene I’m referring to, a young director played by Bogdanovich himself, gets drunk with Orlok while trying to persuade him to do one more movie. Spotting The Criminal Code on the TV, he remarks, “Howard Hawks directed this.” After finishing the film (and several more drinks), he then, almost ruefully, states: “He really knows how to tell a story.” Ultimately, this cinephilia is nostalgic, backward looking, at the same time as it acknowledges the future, summed up in Bogdanovich’s character stating: “All the good movies have been made.” Even the loving shots of a projectionist loading film at a drive-in movie theatre demonstrate the deep love of the whole theatre-going experience.

So, that’s one way of showing how the film shares with Tarantino the value of trash cinema, camp, etc. I mean, really in many ways Bogdanovich was like the Tarantino of the era. The film brat who knows everything about movies (and puts himself in this one, just like Tarantino did in his early works!).

Aren: I agree that both films have a reverence for past cinema, even if that cinema was dubbed camp. But there’s more than simply a similarity between the film and Tarantino’s latest. The climaxes are particularly similar, and both seem to be exploring the blurring between movies and reality, how one informs the other and vice versa.

In the Targets climax, Orlok advances on the sniper, Bobby, with his cane while at the drive-in where Orlok is supposed to give a speech after the screening. Bobby is scared and looks up at the movie screen to see an image of Karloff in The Terror stalking sinisterly forward with a cane. He then looks down to see Orlok doing the exact same thing in person. He shoots at Orlok and he shoots at the screen, because he can no longer distinguish movies from reality, which seems to sum up the entire film. And because of that overlap, Orlok can reach him and clobber him with his cane, stopping the massacre. Compare this to the climax of Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood which has Rick Dalton and Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) dispatch the three Manson killers, with Rick utilizing a flamethrower prop from his movie, The 14 Fists of McCluskey. It’s again the movies themselves that allows the characters to triumph over the killers.

I don’t mean to point this out as a way of saying that Tarantino steals his shocking climax from this film. Rather, I think both films belong to this line of pastiche films, which engage genuinely with B-movie filmmaking, respect its craft, but also think that there’s something more to the art we engage with; that potentially films have the ability to shape reality, or at least shape the way we perceive reality.

Also, Tarantino is renowned for his cinematic homages. I mean, hell, in Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood he even has the same radio disc jockey playing on Cliff’s car radio as plays on Bobby’s radio in Targets. So he’s not above the deliberate homages, even if some of the thematic similarities are probably more due to Tarantino and Bogdanovich both believing in a unique power of cinema.

Anders: Yes, it’s 93 KHJ Los Angeles during its “Boss Radio” era!

Relationship between movies and violence

Aren: I mentioned that Targets deals with the overlap between movies and reality, both in Orlok’s perception of himself, but also Bobby’s violent actions, which take on a movie rampage quality, but are also clearly inspired by the University of Texas, Austin shooting. Thus, Bogdanovich seems to be deliberating wading into the debate between movies and their relationship to violence in real life. Bobby doesn’t seem to be able to distinguish between the two during the climax, and you can’t help thinking that his violence is a result of his believing life is just a movie.

Anders: The film is fascinating because it really gets at the idea that film is on the one hand a reflection of the world — even the Orlok plot is motivated by the idea that real-world horrors are too extreme for people to be scared by old Gothic plots anymore — and on the other, that it has real power — Orlok can stop Bobby.

The relationship between real-life violence and movie violence is really explored to a great effect through the character of Bobby. Clearly he’s inspired by Charles Whitman, the University of Texas, Austin tower shooter, but Bobby in the film is also influenced by his obsession with guns; he’s a real collector, even lying to his wife and mother about the extent of his hobby and why it keeps him late from work. I think the gun connection is explicitly related to movies: “All you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun” as Godard said. So, there’s a strange ambivalence in the film about movie violence. Like Bobby, the film seems to share Tarantino’s almost relishing of it, but never trivializing it. It’s significant.

Aren: It’s probably also worth commenting that Corman often disguised social justice messages within his B-movies. So Targets very much has an anti-gun message (it’s important that Orlok does not stop Bobby with a gun, but a cane) courtesy of Corman, but Bogdanovich complicates the depiction by showing the terrifying excitement of the violence.

Prescience about violence to come

Aren: In a text conversation, you noted the film’s prescience about mass shootings, even as you also acknowledge the fact that it was made after the University of Texas, Austin mass shooting. I can’t help but think of the one shot where the camera takes on Bobby’s POV as he is aiming at his father at the shooting range and seeing an approximation of a video game first-person shooter HUD. Video games did not exist at the time of the film, let alone first-person shooters, but Bogdanovich is creating a visual vocabulary that we would then use to link video games to mass killings, especially with regards to Columbine or the Christchurch New Zealand killer, who attached a Go-Pro to the barrel of his rifle.

Anders: Yes, there’s a lot of POV shots in Targets, even from the perspective of Bobby walking to the car after his first killing of his wife, mother, and the delivery man. The film anticipates that first-person shooter camera, and also the alignment of narrative purpose with that of the killer that you do get in video games. The kills become part of the propulsive drive, inevitable even.

The film also gets into touching on the psychology of the killer. Personally, I often find the ways that motivations are attributed and psychology is utilized in the presentation and analysis of current day mass-killings distasteful, not only for how they are applied unevenly across religious and racial lines, but also for how they both sell-short the seriousness and depravity of these killings.

Aren: I mean, we write this in the wake of the horrifying killings in Nova Scotia, where people are grasping at straws to try to assign a psychological justification to the killer. But what comfort will these rationalizations truly bring?

Anders: It’s true. I rewatched it again last night, with the killings on my mind, and it’s incredibly disturbing how similar it is to the kinds of mass murders we’ve seen in recent years.

In this film, we get some gesture to Bobby’s troubled mind, but there’s no one to blame, short of the entire society collectively: he’s got an apparently loving, if traditional family; a pretty, loving wife, even if she has to work evenings; a mother who cares for him. But it’s clear he doesn’t love his job and something is eating away at him. As he says, at one point trying to confess before pulling away, “I don’t know what’s happening to me. … Sometimes I get funny ideas.”

The fact that Bobby is a relatively successful white man, rather than a clear criminal or someone the audience would have prejudices about—as Tarantino notes, he’s a clean cut boy next door who eats Baby Ruth’s and drinks Coca-Cola—aligns the film as part of a media lineage that points to today’s mass killers, as Whitman did also.

Aren: It’s another way the film seemed to predict a trend that would play out in reality, and thus, only become more relevant in the years since its release.

Targets (1968, USA)

Directed by Peter Bogdanovich; written by Peter Bogdanovich and Samuel Fuller (uncredited); starring Boris Karloff, Tim O’Kelly, Peter Bogdanovich.

Anders and Anton discuss their appreciation of the third season of The Bear and the mixed critical reception to the latest season of the hit show.