Halloween Horror: Dark Water (2002)

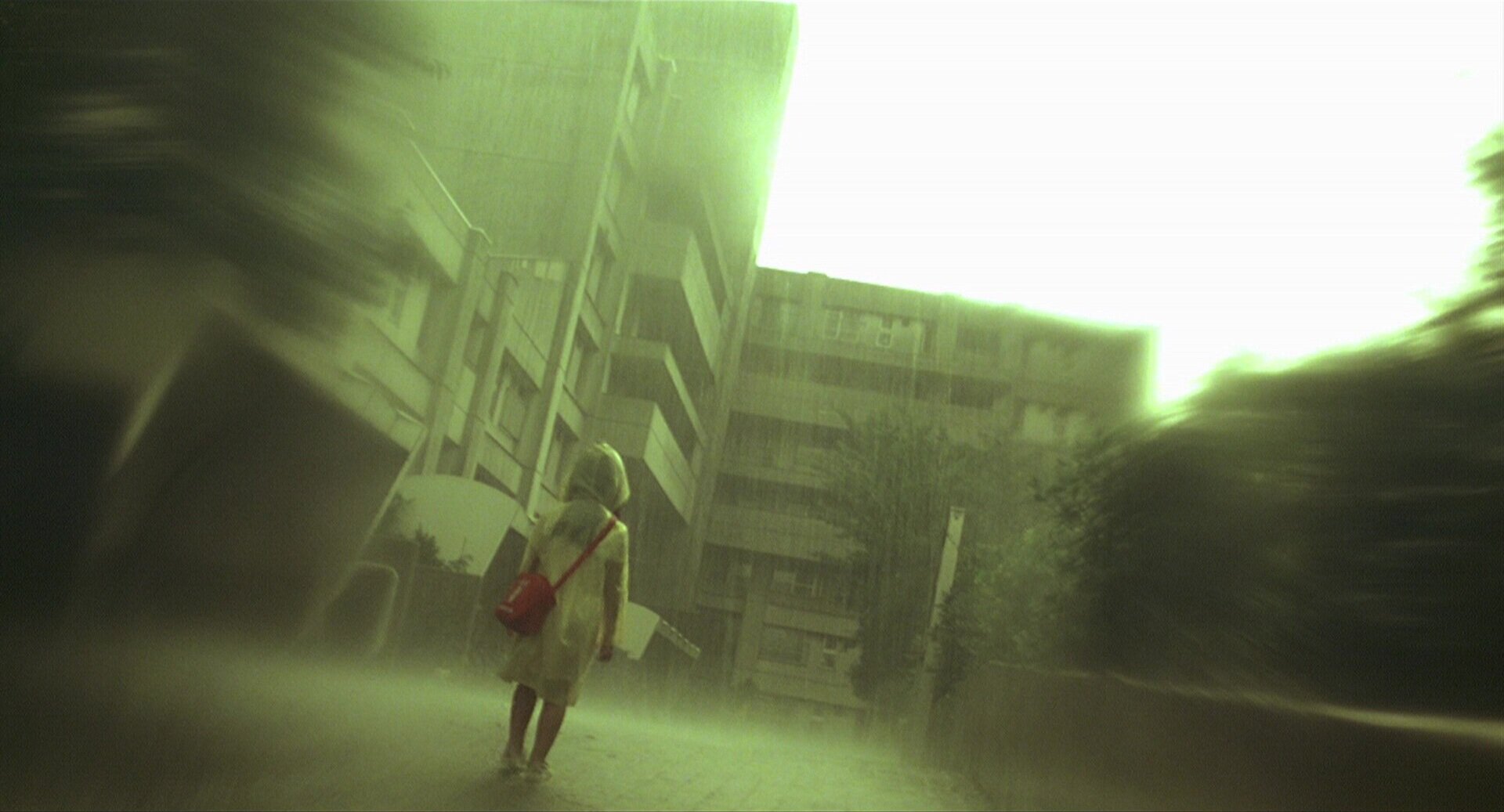

Dark Water is suffused with wetness and effectively creates an atmosphere of fear and anxiety with water. As someone who had a roof leak this past spring, I understand viscerally how the sight of water dripping down from the ceiling creates a special kind of anxiety, leading one to contemplate how bad the leak might be and a sense of dread every time the weather forecast calls for rain. But wetness in this film is more than just a physical danger to the home. It’s a metaphor for the psychological depths from which a personal crisis can surface. Appropriately, the Japanese title of the film means literally “From the Depths of Dark Water,” and from the opening moments of the film, as a young Yoshimi waits on a rainy day for her parents to pick her up at school, water is associated with sadness, with fear of loss and abandonment, and with the family traumas and disintegration that forms the real source of the film’s power.

In many ways Dark Water, from Ring director Hideo Nakata, is fairly representative of Japanese horror, or J-horror, films. Like many J-horror films, it is set in modern society, which offers no protection against atavistic spirits. Dark Water draws on supernatural elements, including ghosts and the concept of onnen (怨念), the idea that some emotions are so strong that their power can extend from beyond the grave. The film’s damp settings are also typical of the genre in Japan. In contrast to Western spooky tales, which often take place in dry or musty mansions, basements or cemeteries, Japanese culture associates spirits with wetness and humidity, an association made in Nakata’s Ring as well.

But for a Western audience expecting relentless violence and shock typical of some other J-horror classics, Dark Water might surprise with its focus on generating a creepy atmosphere and sense of anxiety instead. While there are some scary scenes in Dark Water, it is rarely truly terrifying. The unbearably and emotionally heart wrenching aspect of the film comes from its everyday human drama, telling the story of a young woman, Yoshimi Matsubara (Hitomi Kuroki), who is fighting for the custody of her daughter in a bitter divorce.

Yoshimi is being divorced by her husband, who hopes to gain full custody of their daughter, a kindergartner named Ikuko (Rio Kanno). To strengthen her case, Yoshimi gets a job and rents a run-down apartment to live in, enrolling her daughter in a kindergarten nearby. One day, a leak appears on the ceiling of their apartment, but when she complains to the superintendent, he does nothing about it. Soon, strange things begin happening around the apartment complex, including the appearance of a child’s red bag that defies attempts to dispose of it, and glimpses of a young girl in a yellow raincoat. When Ikuko falls ill after seeing the girl in the raincoat, Yoshimi discovers that a young girl from Ikuko’s kindergarten had gone missing two years earlier, and that the empty unit above theirs has become completely flooded after someone left the faucets running.

One of the themes of the film is the terrible treatment of women in Japan, how they have been painted as unreliable and hysterical. While Yoshimi’s lawyer notes that for children under five, the courts often favour mothers in custody hearings, in Japan the father’s parental rights are often paramount. Any missteps on Yoshimi’s part could hurt her case. In the course of the divorce mediation, we discover that Yoshimi has had mental health trouble in the past, something her ex-husband and his lawyers try to leverage to prove Yoshimi unfit to care for Ikuko. The fear that your own sanity could be used against you to take away your child at the slightest misstep adds to the film’s anxiety inducing tone. The film dramatizes the strain that the strange events in the apartment take on Yoshimi’s mental health. When combined with the pressures of trying to care for Ikuko, as a single mother struggling to hold down her copy editing job, it results in honest, but nail-biting mistakes, such as when she shows up late to pick up her daughter at kindergarten only to find her gone. This gives the film its cross-cultural relatability and is a trope that shows up in horror films in East and West.

The supernatural plot, concerning the ghostly, missing girl, and the wet apartment complex, could even be read as a metaphor for the divorce and a manifestation of Yoshimi’s fear of losing her daughter. But it's not merely a metaphor, as the film takes the supernatural seriously, even if the line between the supernatural and psychological or emotional stress is not as neatly divided in Japanese culture, given the aforementioned notion of onnen.

Nakata develops the narrative as a slow burn, dropping the supernatural scares into scenes that also develop the bond between mother and daughter. It’s never in doubt that Yoshimi cares for Ikuko. Dark Water is a story of decent people caught up in personal and supernatural tragedy. The forces arrayed against them, whether supernatural or human and legal, follow a logic, but can feel inevitable.

The American film that Dark Water recalls the most in terms of structure and content is M. Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense, although the twist in Dark Water is less surprising and fairly easy to see coming. The film’s muted in terms of shocks, but develops its atmosphere with careful camera work and the use of blue filters that leave the film feeling damp throughout.

While Dark Water might not be as terrifying as some audiences might desire it to be, it more than makes up for that with its compelling human drama. Dark Water is not just creepy, but it’s sad as well. Frankly, the very real fears Yoshimi faces in the divorce are as nightmarish to a parent as anything the supernatural can offer. The film seems to agree, as the coda set 10 years later suggests a more reassuring role for the spirit realm than you might expect. By balancing the atmospheric, ghostly scares and a more compelling human drama, Dark Water sacrifices none of its J-horror bonafides to tell a story that resonates beyond the genre.

8 out of 10

Dark Water (2002, Japan)

Directed by Hideo Nakata; screenplay by Yoshihiro Nakamura and Kenichi Suzuki, based on the story by Koji Suzuki; starring Hitomi Kuroki, Rio Kanno, Mirei Oguchi, Asami Mizukawa, Fumiyo Kohinata, Yo Tokui, Isao Yatsu, Isao Yatsu, Shigemitsu Ogi.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s horror drama is a quiet film with a haunting effect that’s as disturbing as anything you’ll find in horror cinema.