Table Talk: The Irishman a.k.a. I Heard You Paint Houses (2019)

A Definitive Statement on Gangster Pictures

Aren: I feel like this movie has been coming for a long time. Like Silence, it seemed to show up on lists of upcoming productions for the past decade and a half. In fact, I remember seeing it listed under Martin Scorsese’s filmography on IMDb back in the day before they hid future productions behind the IMDbPro paywall. The reason I bring this up is because The Irishman, titled on screen as I Heard You Paint Houses, feels like a film that Scorsese had to make sooner rather than later. And even though I was anticipating the kind of film it ended up being, I don’t think I was ready for just how mournful and staggering this film is. Scorsese has made a 209-minute thesis statement on the gangster picture, a genre he had more than a hand in shaping.

Anders: “Staggering” is a good word. It leaves you reeling, but not in the ways that you might initially expect. It absorbs you with its length—at 209 minutes, it’s in the realm of Seven Samurai (1954), Lawrence of Arabia (1962), or Gone with the Wind (1939). It takes you on an emotional roller coaster, making you care for these characters and then heartbroken by where they end up. And it covers a vast swath of American history, from World War II to its post-9/11 coda, the Kennedy assassination to Nixon’s downfall, but it also offers insight into a figure at the margins of this history, someone who gets wrapped up in it all until they themselves end up making history—even if their role in it is a secret.

People keep describing the film as a “gangster film,” but I don’t think the label does the film justice in many ways. It might lead people to expect the wrong things from the film, and while it does connect with Scorsese’s other films about gangs and their role in American culture, this functions effectively as a kind of coda to the discussion. As someone remarked on Twitter, of all of Scorsese’s films about this subject matter, this is the one least likely to be misread as “romanticising” gangster culture.

If anything, The Irishman deserves some comparison to Scorsese’s last feature, Silence (2016), in its exploration of religion. The Irishman goes further than merely depicting the Roman Catholicism of the Irish and Italian gangsters at baptisms, etc. It underlines the role that religion plays in offering a community to these men through their shared faith. Consider the “meal” of bread dipped in wine that Frank Sheeran and Russell Bufalino share as old men in prison. But it goes even further. In the film’s final minutes, when Frank is confronted with his deeds and attempts to wrestle with them, seeking absolution through confession with a priest, the film becomes about issues of eternal value.

Aren: Definitely agree with the Silence connection. This film belongs in the conversation of his “religious” pictures.

But it’s still a gangster picture. As well, I’ve still seen the woke scolds reading the film as another glamourization of gangsters—as if all of Scorsese’s previous films were nothing but endorsements of their subject matter. (I don’t understand how supposedly-smart people continue to be so dense when it comes to depiction versus endorsement.) Also, in so many ways, The Irishman is in conversation with other Scorsese pictures, particularly his gangster films: Mean Streets (1973), Goodfellas (1990), Casino (1995), Gangs of New York (2002), and The Departed (2006).

Anders: Yes. Even though the pigeon-holing of Scorsese as a “gangster film director” rankles (it is only six films out of his 50-year career), his films operating in the genre address a very wide range of themes and approaches to the subject matter. Mean Streets is personal, a possible reflection on Scorsese’s own youth and his relationship to the Italian-American gang culture of New York City; Goodfellas and Casino address real-life figures, either directly or with pseudonyms, and explore the history of the mob in the mid-twentieth century; The Departed shifts the focus to Boston and the Irish gangs, pairing in many ways with Gangs of New York which explores the history of Irish and nativist gangs in old NYC. All the films deal with the role that the mob plays in the life of American immigrants from Europe in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century.

So, The Irishman addresses aspects of all these films: the Irish-Italian mob connections and their function within the power establishments of business, labour, and politics. But it also functions as a kind of coda to Mean Streets, making it personal again. It’s very much an old man’s film, in that it is about reflecting on—or not reflecting on—a life and the journey and decisions that were made along the way.

Aren: Yes, it’s a reflection, but a key part of that reflection is on the genre as a whole. Scorsese seems to be making some definitive statements about the mob and the moral toll of this way of life. It’s not a correction of any earlier depictions of exuberance in a life of crime—most notably in Goodfellas, which is as much about the thrill of being a gangster as about its moral cost—but it does comment on those films and offer parallels to those films, while also giving a very different emotional tenor to the action on screen. It’s so meaningful because Scorsese has defined how we view American gangsters, and so now it seems like he’s offering his final statement on the subject, closing the book so to speak. If he ever made another gangster picture, I’d be shocked, so that’s why I feel confident in calling The Irishman “the definitive statement” on gangster movies. What more is there to say on this subject?

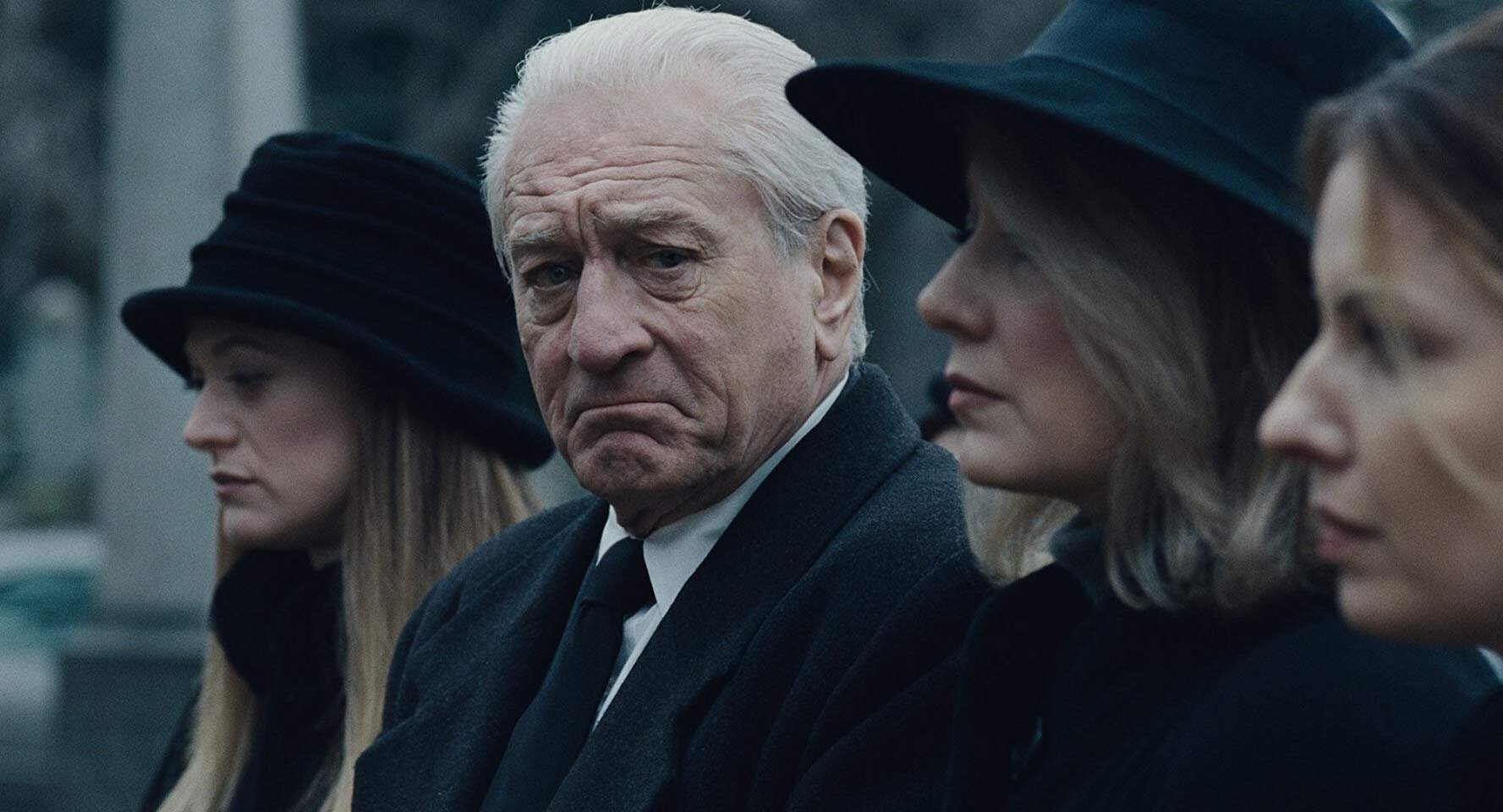

The Iconic Actors

Aren: The Irishman brings together Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, and Al Pacino on screen for the first time. It’s crazy that it took us this long for them to all be in a film together, but now that we have it, I almost wouldn’t have asked for it any sooner. The cumulative effect of their appearance together is enormous, and works especially well in a film that is as much a reflection on the genre as this one.

Anders: It’s a real wealth of great performances from some of the most iconic actors in the gangster film tradition. Of course, Pacino and De Niro are central to the effect of the film, in part because of their roles in The Godfather films. They give the film a legitimacy, since The Godfather plays an interesting role in both shaping and reflecting the reputation of the Italian mafia in America.

Aren: There are a lot of connections to The Godfather here, not least of which are the actors. Think of the final shot: the closed door in The Godfather compared to the door just ajar here. It seems to be the Scorsese film that most openly deals with the gangster genre outside his own work.

As for the performances themselves, De Niro is his usual icy self here. The unnatural grey-blue of his eyes here—which Scorsese managed through digital effects—is eery, externalizing the coldness of the character. Pacino is his usual, late-career big performer self here, but it’s perfectly suited to Jimmy Hoffa, who was a larger-than-life figure if there ever was one. Pesci is the one who surprises me most here, as he is such a motormouth and such a ball of fiery energy in Goodfellas and Casino and here he’s so quiet, which makes him all the more terrifying.

Anders: Absolutely. Since Pesci is the one who has been away from acting for the longest time, it also feels like his return is a greater thrill than it would have been otherwise. He’s so good in the film because he draws on his reputation in earlier works as an impulsive firecracker, but Russell Bufalino is a quiet and dangerous character. Because of Pesci we keep expecting him to lash out, but he remains in careful control throughout.

Also, note some of the other supporting roles. Ray Romano shines as Bill Bufalino, Russ’s lawyer brother, using his comedic chops but also feeling perfectly at home in this world. It was one of the most surprising roles for me in the film. But it should be noted that in many ways The Irishman is very funny. It’s a comedy at times, especially in its early moments.

Aren: Definitely. I don’t want to mislead people into thinking it’s all dour and gloomy. The film’s epilogue is especially depressing, but much of what comes earlier is fun and fast-paced. The performers are having a lot of fun with the material. Pacino is especially light and hilarious. His incredulous rage at Tony Pro (Stephen Graham) showing up late is amazing and mined for all its comic worth.

Anders: I enjoyed seeing some of Scorsese’s old and new collaborators in the film as well. It was nice to see Harvey Keitel in the film, but Scorsese also employs some new faces. On the one hand we have Bobby Cannavale and Stephen Graham who were in the Scorsese-produced Boardwalk Empire (Graham played Al Capone in the show). And then we have Jesse Plemons and Anna Paquin as the representatives of the next generation, both in the film and as actors, playing key roles in the film as Jimmy Hoffa and Frank Sheehan’s kids, respectively.

Aren: Paquin makes a big impression here. The calculated silence of her character and the way that she’s always watching her father, with no illusions as to his line of work and its moral consequences, is haunting. Adam Kempenaar of Filmspotting mentioned in his Letterboxd review that she’s the closest thing to God in this film, as she is all-seeing and all-knowing, and I think that rings largely true. Again, woke complaints about her lack of lines in the film miss the whole point of the character, and the exceptional work of the performer.

Formal Repetitions and Mirroring Structure

Aren: I alluded to it earlier, but a large reason why The Irishman is so effective is because of its structure and the way it repeats elements of earlier Scorsese pictures, while giving them a new look. For example, the voiceover narration and the way hit music from the time period plays on the soundtrack is classic Scorsese, and even the method of having on-screen text indicate how a character eventually dies whenever a new character shows up on screen seems like the kind of high-energy, subjective filmmaking that Scorsese has made famous. But when you start to think about that text, it’s not as simple as the freeze-frames in Goodfellas. It’s funny the first few times, but the sheer volume of the text, which occurs on screen for minor and major characters throughout the film, shows how almost all of these people died horrible deaths. It is a way of Scorsese having a pallour of doom over the entire film, sneaking in morbidity through some repetitive-seeming formal tricks.

Anders: The use of titles gives the film a sense of foreboding, but it also becomes almost comical through repetition, and then Scorsese undercuts it with the one title of the gangsters, saying “died of natural causes, well regarded by all,” which had my audience laughing quite loudly. It’s a dark humour that serves the larger themes of the film.

Aren: It’s also key that Scorsese doesn’t have Jimmy Hoffa at the centre of the film. I forget which critic mentioned this on Twitter or Letterboxd (it was several weeks ago), but they said that the film does something different for a Scorsese picture, which is take the impulsive, doomed individual and make him a side character (Hoffa here), while allowing the stoic, steady, heartless supporting character to operate as the film’s centre (Frank here). It allows the entire film to have a more reflective structure, since Frank is more witness to history than active agent in it. He’s the last man standing and he is always observing his life. Even when he is murdering people, he seems detached, as if he’s simply watching himself go through the motions of what he thinks is necessary.

This approach is best exemplified in the moment where he reflects on making two enemy soldiers in World War II dig their own graves before murdering them. He mentions that they still dug their graves, even though they must’ve known that he was going to kill them the moment they were finished, but that they must have held out some irrational hope that simply doing a good job digging the grave and being compliant would let them off the hook of their inescapable fate. That scene is a microcosm of the film as a whole. Frank always does what he’s told and he thinks it’ll let him off the hook of whatever moral damnation is accrued from being an agent of evil. But as we see at the end, he’s left with nothing but guilt (even if he feels no emotional remorse). He may be alive, but he’s been essentially stripped of his humanity.

Anders: I love the structure of the film. It’s got multiple bookends and framings. The first of old Frank telling his story to an unseen person (to us the audience in a very real sense, through direct, extra-diegetic address) in a nursing home, then of Frank and Russ’s road trip to Detroit with their wives, the significance of which only becomes apparent part way through the film, as Frank takes a detour to murder his longtime friend, Jimmy Hoffa.

My friend Dave pointed out that the entire centrepiece of the film, the killing of Hoffa, is edited in palindromic or mirroring structure around the actual killing, which itself is ugly, unremarkable, and sudden. We see the same series of shots: driving to the house, going to the hotel, the airport, etc. in reverse order after the killing. Then the film’s bookends conclude, we get the wedding of Bill’s kid in Detroit, then we have the emotional crescendo of the film, when Frank’s daughter, Peggy, stops talking to him, realizing that he killed Jimmy. This leads us to Frank’s time in the nursing home, but then his life goes on a little longer, as he tries to impress people with pictures of himself and Hoffa (most young people and newer immigrants don’t know who he is). Finally, he ends the film alone and isolated, not just from family, but from his own understanding of himself and the moral reckoning that one would expect to come.

I think the ending of the film is key in showing Frank’s lack of understanding of his own situation and what got him where he is. Frank seeks absolution for betraying and killing his friend, but what he fails to comprehend is the entire rest of the film and how that set him up for it.

Aren: Like the soldiers he murdered during the war, he thought the people giving orders would let him off the hook. That he would get some reward for being a good soldier, so to speak. But as Proverbs 14:12 tells us, “There is a way that appears to be right, but in the end it leads to death.” Frank has lived his entire life on a false premise and he will reap its false reward.

The Irishman a.k.a. I Heard You Paint Houses (2019, USA)

Directed by Martin Scorsese; written by Steven Zaillian, based on the book by Charles Brandt; starring Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Joe Pesci, Ray Romano, Bobby Cannavale, Anna Paquin, Stephen Graham, Harvey Keitel, Stephanize Kurtzuba, Kathrine Narducci, Welker White, Jesse Plemons.