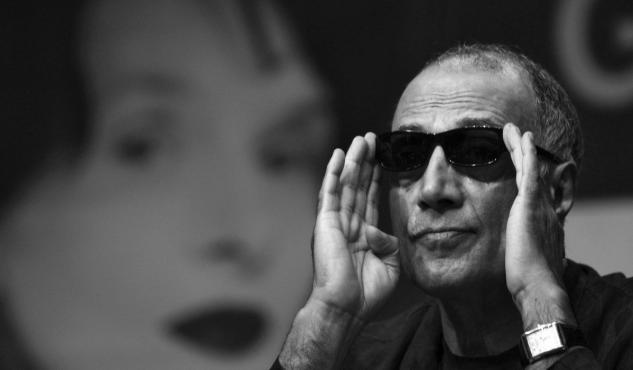

Remembering Abbas Kiarostami

I didn’t grow up with the films of Abbas Kiarostami but I still know his death is a loss. The Iranian writer and director died from cancer at the age of 76 on July 4, 2016 while undergoing treatment in France. He was the titan of Iranian cinema. With films like Close-Up he broke the mold of what a film could do. He didn’t make movies that followed any rules. His films were rooted in reality—historical, personal, biographical—but they weren’t documentaries. He dreamed up the scenarios he filmed, but he didn’t avoid reality when it confronted him head-on. His films were fluid. He allowed happy (or not-so-happy) accidents to bleed into his works and create films that defied easy categorization.

Other filmmakers took notice of what he was doing. Jafar Panahi, who is now considered a master in his own right, was once Kiarostami’s protegé. He continues to make films inspired by Kiarostami’s pioneering work, although with a more-pointed political bent.

I have not seen all of Kiarostami’s films but I love the ones that I have seen. Each of his films feel like a discovery. They’re so unlike other movies. They’re art films, but there’s nothing artificial about them. They’re formally exact, but they don’t feel hermetically-sealed. Kiarostami loves to restrict the frame, especially in the front seats of cars, but that restriction doesn’t shrink the world down to just the two characters. Instead, it focuses in on a piece of a larger whole. He wants you to watch only two characters for extended sequences, but he doesn’t erase what exists beyond these people by doing so. This makes his films feel alive in ways that so many independent films do not.

As well, his films lack the ego that defines so many great films—and filmmakers. Great filmmakers are notorious for showing off. Think of some shots in the films of Christopher Nolan or David Fincher or Paul Thomas Anderson—hell, even Martin Scorsese. The opening steadicam of Boogie Nights or Jordan Belfort’s fourth-wall breaking introduction in The Wolf of Wall Street are great shots, but they’re more-than-a-little egotistical. They make you notice just how good Anderson or Scorsese are at crafting cinematic moments and don’t let you forget who crafted them.

Kiarostami never draws this sort of attention to himself. Even showy moments, like the masterful opening of Like Someone in Love, are not egotistical. This opening restricts the frame of a restaurant in Tokyo so that we’re unsure who is speaking and who is being spoken to. We only hear a voice and watch the people at the other tables in the restaurant. When Kiarostami finally cuts to a reverse shot, it’s breathtaking simply for the fact that we see the speaker. The scene is a masterclass in withholding information, and then carefully, patiently, revealing it.

This scene is self-aware. It’s constructed in a deliberately cinematic way; if it were another art medium, the context could not be withheld in such a way. All of Kiarostami’s films are self-aware. But they are self-aware in the way a great poem or novel is—not in the crassly cynical way that modern Hollywood has championed as “clever.” They reflect Kiarostami’s unspoken relationship to the films he makes and the people he films. It’s about a director’s moral duty to his or her work and subject matter. This is never more evident than in The Wind Will Carry Us. Again in this film, Kiarostami withholds the context of the situation we are watching. A man is in a small Kurdish village to observe an old woman’s final days. Initially we believe he’s a visiting family member, but soon enough, we realize the man is writing an article on the cultural practices of the village. He’s taking advantage of their grief for the sake of his art.

Kiarostami filmed The Wind Will Carry Us in a remote Kurdish village and took advantage of the village’s poverty for the sake of his film. Many of the scenes in the film are unscripted and the village characters are often unaware of the context of the film. They don’t know what Kiarostami is doing. Kiarostami takes advantage of reality to make a film about taking advantage of others and makes the film an examination of the morality of such an action. The film examines itself. It asks whether the character (and Kiarostami) is guilty of crossing a line and lets the viewer decide the answer.

Is the character’s simulated guilt equal to Kiarostami’s own guilt? Is there a difference between real and imagined injustice? If the real and the fake are indistinguishable, does it matter? This question is the central preoccupation of Certified Copy. Again, the film is self-aware and showy, but not in the usual ways we expect great films and filmmakers to be. Certified Copy introduced me to Kiarostami’s work. Because of this, and because of the age I was when I saw it, the film holds a special place in my heart. It has informed my own view of romance and the question of artistic worth.

The film questions whether a facsimile of something is as valuable as the real thing. First, it asks this in terms of art, such as whether a copy of a beautiful painting is as valuable as the original painting since the copy produces the same joy as the original. However, Kiarostami doesn’t stop there.

He shifts the exploration from art to relationships. This happens during an abrupt change in the film when a stranger presumes that Juliette Binoche and William Shimell are married and Binoche does not disagree with the presumption. From then on, the characters act as if they are married. They argue about no longer having the same connection they did in the past. They wonder if they can recapture the love that once was there.

Kiarostami isn’t making a puzzle movie here. You’re not meant to solve whether Binoche and Shimell actually are married. Instead, he’s discussing a marriage in much the same way a great work of art. If a woman only pretends to be her best self for the sake of her partner, is that any different than actually being her best self if the effects on her partner are the same? Again, Kiarostami does not answer this question. He lets us ponder its profound relevance. His films always leave us with some questions that seem vital to our everyday lives.

I look forward to discovering more films by Abbas Kiarostami, but I’m sad that that list of films is now finite. We lost a great filmmaker this past week. Let’s not forget him.

Rest in peace, Abbas Kiarostami, 1944-2016.