TIFF23: Mandoob

In the Western imagination, Saudi Arabia is usually a land of stereotypes and caricatures: bearded Arab men in robes wearing red keffiyehs; Muslim pilgrims circumnavigating the Kaaba during the Hajj; massive oil fields lighting up the stark desert. The reality, as is always the case, is more complex. Ali Kalthami’s Mandoob, his debut feature about a down-on-his-luck food delivery man navigating the Saudi capital Riyadh, offers a corrective to our limited Western imagination about Saudi culture. It’s a compelling character piece with a refreshing dose of comedy that has the added benefit of letting Western viewers see Saudi Arabia on its own terms.

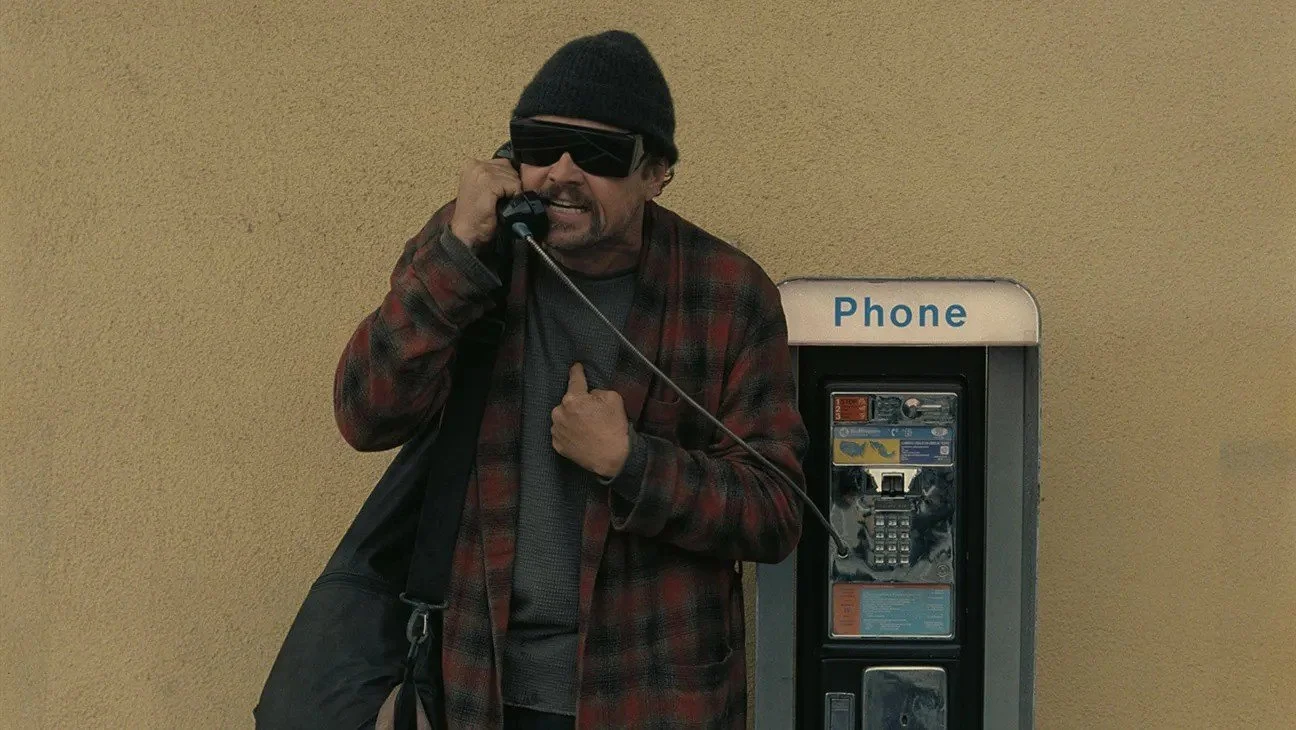

The film follows Fahad (Mohammed Adokhi), who in the early scenes is failing to balance work as a delivery driver or mandoob with his day job in a call centre. Fahad is already overextended, taking care of an ailing father when he’s not on the job. Of course, the delicate balance doesn’t last and after hilariously blowing up on his boss, he’s fired and his side hustle becomes his main hustle. Fahad wants a way back into respectable society, so when he notices a fellow mandoob selling liquor to a wealthy businessman, he follows him back to where he stores the liquor, thinking that maybe some elicit sales are just what he needs to change his luck.

Of course, Fahad is doomed to fail. The film begins in medias res, just as Fahad’s bad decisions are catching up to him, before flashing back two weeks to show us how Fahad got into this desperate situation. The film doesn’t generate tension with the question of whether Fahad will mess up, but with how. In that sense, Mandoob shares a lot with films of the past, especially post-war noirs and character dramas like Fritz Lang’s Scarlet Street that follow a sympathetic but ultimately pathetic fool who makes one bad decision after another. The character is doomed, but our investment in the character is predicated on the possibility that he might save himself before it’s too late.

This description makes Mandoob sound like a dour drama, but it’s laced with a good deal of comedy. Much of this is the result of Adokhi, who has an expressive face, large eyes, and a sad smile that makes him lovable, albeit pathetically so. Kalthami and cinematographer Ahmed Tahoun focus on Adokhi’s face throughout the film, watching him in close-up as he watches other characters and suffers indignity upon indignity. The camera, and by extension, the viewer, waits for Fahad’s smile to turn sour, for the big, warm eyes to fill with anger, for the well-meaning demeanour to turn into abject frustration.

A scene early in the film captures this visual approach. Fahad is asked to sign a resignation letter to save everyone the hassle of firing him and he’s handed a pen. The camera wavers on his face looking down at the pen, and holds, and holds, as we see his frustration grow until it cannot be suppressed any longer. And then he drops the pen and explodes in ill-timed yet understandable anger. It’s hilarious. Adokhi has a background in comic shorts, so it’s no surprise he’s physically adept at the comedy, whether brandishing a fire extinguisher as a weapon or retching at the taste of whiskey. There’s a comedian’s physicality to how he holds himself and reacts with large, spontaneous movements.

Adokhi is good in the darker and quieter moments as well, which also rely on his face to carry the storytelling. Fahad goes out for dinner at a fancy restaurant with his crush, Maha (Sarah Taibah), thinking it’s a date, but she brings two of her coworkers and spends most of the meal complaining about their Western boss. Maha and her coworkers code-switch between English and Saudi, and essentially ignore Fahad, as well as the fact that dining out in this restaurant is clearly a big occasion for him. For them, it’s just the place they go after work. Kalthami focuses on Adokhi’s face as he tries to keep a patient smile. Unlike the earlier scene, Fahad doesn’t explode in anger, but the transition from anticipation to confusion to frustration is fascinating to watch in his eyes.

The scene also captures the emergent class differences in Saudi culture. Fahad goes to the restaurant dressed traditionally in his best robe and keffiyeh, but Maha and her coworkers show up in more modern dress. They fiddle with their phones, the women don’t wear hijabs or abayas (which is allowed with the recent cultural changes that are part of Saudi Vision 2030), and they speak English. They belong to a different class than Fahad, so no matter how much Maha may humour him, she knows she’s too good for him. He’s just a mandoob with dreams of being something more. The whole scene recalls moments in Scarlet Street. Fahad’s hapless desire to be more than he is and thus on the level with a woman like Maha is similar to Edward G. Robinson’s Chris’s delusions about Kitty being in love with him in Lang’s film. Both protagonists see what they want to see until they finally see reality, and it’s heartbreaking.

It’s perhaps setting the bar too high to compare Mandoob to Scarlet Street, or to a more obvious influence like Vittorio de Sica’s Bicycle Thieves. As well, the wet streets of Riyadh, which diffuse the car lights and street lamps in the film, recall the slick Chicago streets of Michael Mann’s Thief—another key influence mentioned by Kalthami. Mandoob is not on the level of these classics. For instance, its plotting is rather obvious, the visual construction of most scenes mostly functional, the pacing somewhat uneven. But it’s a strong debut. The film’s strengths lie more in its characterizations and its ability to blend humour and pathos in its exploration of this one man’s downfall. Ali Kalthami is cinematically literate, and Mandoob is a film in dialogue with the past, even as it charts a new course in Saudi cinema—both within the nation and without.

7 out of 10

Mandoob (2023, Saudi Arabia)

Directed by Ali Kalthami; written by Ali Kalthami and Mohammed Algarawi; starring Mohammed Aldokhi, Hajar Alshammari, Mohammed Alttowayan, Sarah Taibah.

Ben Leonberg’s Good Boy succeeds entirely due to its novel concept and the very good dog at its centre.