Roundtable: The Power of the Dog (2021)

The Power of the Dog and Westerns

Anton: Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog, her new Western based on the 1967 novel by Thomas Savage, is one of the leading contenders for awards season this year. The Power of the Dog hit Netflix at the start of December, and even though I watched it over the winter holidays, I’m still reexamining the film in my mind, which is probably a testament to its many layers. As a Jane Campion film, I expected it to be precise and artistic. It’s certainly well-made, but there’s also a lot to unpack, and I’m uncertain about parts. I can’t tell if I like the movie, even if I admire much of it.

Aren: I think that’s fair, as this is a very deliberate film, with a patient pace to the storytelling and some strong ideas about masculinity that work in opposition to the genre conventions (or at least perceptions about those genre conventions). However, I would strongly recommend that you (and our readers) avoid most criticism on The Power of the Dog. For every good review (such as the one by Josh Larsen over at Larsen on Film), you get some dreadful and reductive takes which make the film sound like some hot-take Western as opposed to a considered work of art. Essentially, much of the criticism and almost all the talk on Twitter has painted the film as a simplistic take on “cowboys are toxic,” which is really not what this film is about at all. In my mind, The Power of the Dog is a hypnotic drama about a Freudian power game between men, which ends up making some provocative comments about different kinds of masculinity, which are represented by its core characters.

Anton: The Western is such a codified genre that, making one today, you are essentially working either with or against those established conventions. The Power of the Dog is a substantial and thoughtful engagement with the genre, but there is something subversive about the film’s approach. I don’t think “cowboys are toxic” is so far off from a summation of the film’s message. But I agree that it’s thankfully not that simplistic. The Power of the Dog is both considered and critical of the genre.

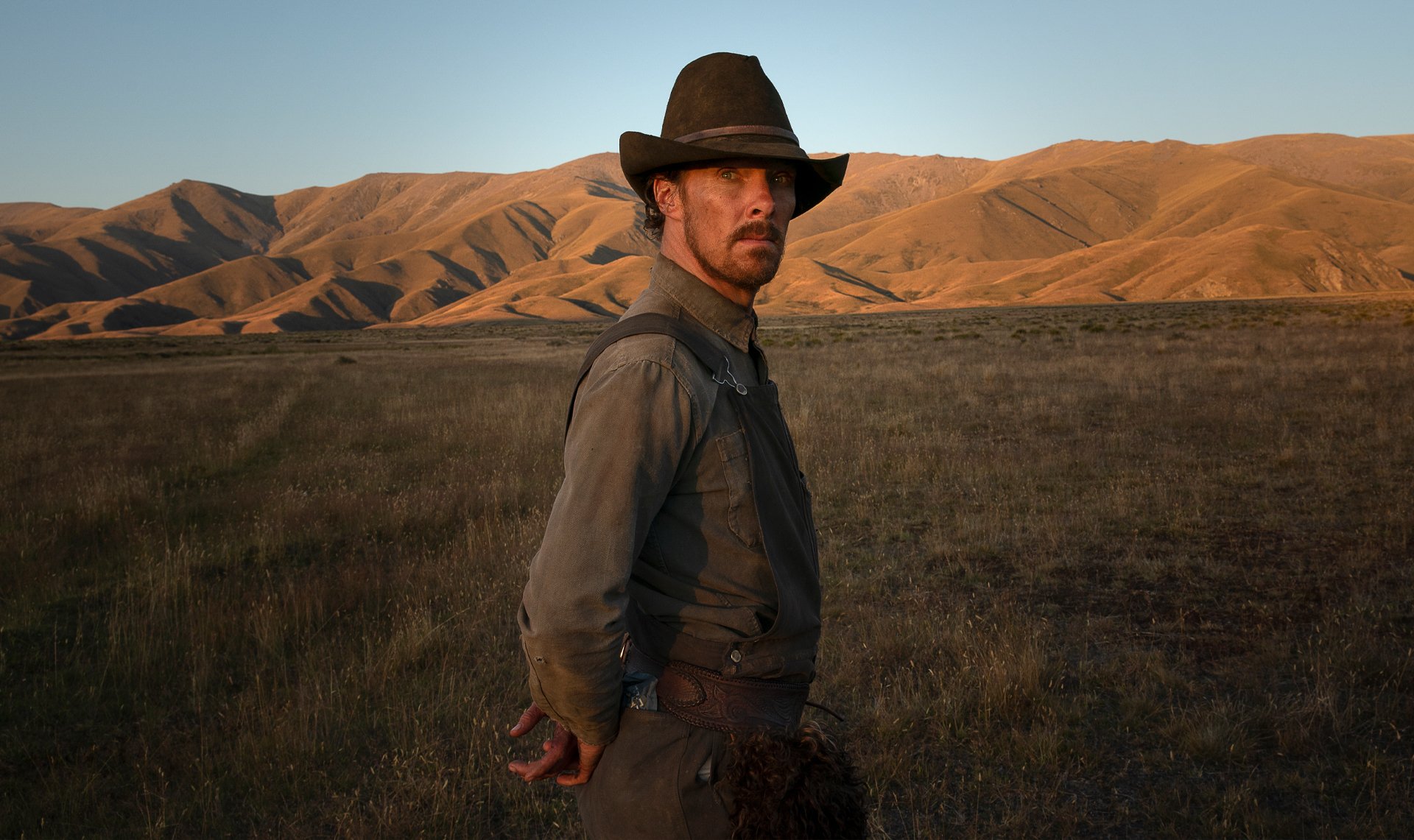

I also don’t think every noteworthy alteration works for the film. For instance, I’m not sold on New Zealand sitting in for Montana—it doesn’t look like Montana, especially after watching so much Yellowstone recently.

Aren: Yes, I agree with you on your comments about shooting in New Zealand. It’s obviously not Montana, and, after watching The Power of the Dog closely after revisiting The Lord of the Rings films, it’s even more obvious that the volcanic landscape with sparse, golden brush is not the American West. But I also think this choice might be deliberate beyond simply working in Campion’s native New Zealand.

Anton: You’re right, in that the choice of shooting location might add to the film’s reworking of the genre—the New Zealand landscape defamiliarizing the mountains and plains of the conventional Western. And after all, the Spaghetti Westerns did something similar, shooting in the deserts of Spain and around Italy.

I was also intrigued by the film’s importation of Gothic trappings to the Western genre, to the point of evoking aspects of a Brontë novel.

Aren: This film is not naturalistic. It’s rugged in some of the characters on screen, but it’s not a raw look at the real American West. Rather, it’s a stylized and tilted vision of the West. We’re not dealing with mundane reality here, but instead, extreme iconography, which plays into the Brontë connections you mention. Thus, the use of a fantasy landscape plays into the surreality of the filmmaking. This is not the West. It’s “The West.” It’s as much about our conception of the West, and more importantly, its characters’ perceptions of it and what it means to be a cowboy, than it is about the historical record.

In many ways, The Power of the Dog reminds me of other films playing with Gothic mystery and iconoclastic visions of the West and manhood. In particular, as Josh Larsen mentions in his review I link to above, the film has aspects of Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940), Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955), and Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (2007)—and not only in the music by Jonny Greenwood.

Anton: There are definitely Gothic aspects, for the story involves the arrival of a new wife to a large and imposing country house, and there are hints of secrets behind the strange, antagonistic, menacing behaviour of the brother-in-law, Phil Burbank (Benedict Cumberbatch)—although it’s more typically the husband or single lord in Gothic narratives.

The way Campion depicts New Zealand’s sparse landscape reminds me just as much of the Scottish Highlands or the Yorkshire moorlands as the American West, so I’ve been thinking about William Wyler’s Wuthering Heights (1939) in regards to this movie. The architecture of the huge country house also recalls the manor in the 1943 version of Jane Eyre, starring Orson Welles.

Aren: For me, the big connection is Claire Denis’s Beau travail, which shares a similar homoerotic tension and portrait of a truly angry, self-destructive man. There’s even a reference to Beau travail in the shot through the window of the shirtless cowboys going about their work in the yard, their muscular torsos glistening in the sun. It’s a recreation of the famous morning training sequence in Denis’ film.

But before we dig in further, we shouldn’t leave out Anders’ initial thoughts.

Anders: OK, thanks. So, I really liked The Power of the Dog. I agree with Aren: tune out the critics. This is a film that is actually attempting to express ideas through the filmic form—a rarity these days.

Counter to Anton’s take, however, I guess I’m not sold on the idea that this is as much a “deconstruction” or “subversion” of the Western, apart from the fact that contemporary genre explorations (whether in the Western or film noir) are able to be more explicit about sex and violence than in the past. So, while I’d agree with Anton that the Western is a particularly codified genre—as, arguably, all of the most specific genres beyond umbrella categories like “comedy” or “drama” are—I don’t see The Power of the Dog pushing the coded elements beyond their breaking point. Most of the elements that Film Twitter folks have latched onto are things that, to varying degrees, are present in older explorations of the genre. In other words, this isn’t so much an “anti-Western” with a didactic social-message, but a use of the genre to explore psychological and elemental themes, which admittedly are more freely portrayed in contemporary stories than in the past.

Anton: But that new emphasis, or even exaggeration, of certain elements present in the Western goes beyond what was previously manifest. Would you agree that Campion wants us to rethink or resist or revise aspects of those old films?

Anders: Perhaps. Whatever her intentions with the film, I’m not convinced that it’s as radical as you or its advocates are saying. “Going beyond” isn’t the same thing as subversion. I think it’s just an amplification of focus. In many ways I could see this same film having been made in the 1950s as a kind of Western noir, ala The Night of the Hunter, which Aren alluded to, but starring, say, John Wayne or some other stoic and gruff actor as Phil, and an Anthony Perkins or James Dean as Peter, who’s played by Kodi Smit-McPhee here. It would work really well, even if it was more circumspect in some of its thematic treatment. I guess this suggests that I think the modern take on the genre here is less in the overall codified elements, but in the off-type casting of Cumberbatch as Phil. Though I actually think Cumberbatch is very good in the role.

Anton: I think Brokeback Mountain (2005) is another good reference point for this movie. (Not to mention the fact that Annie Proulx, who wrote the short story “Brokeback Mountain,” helped revive interest in the works of Thomas Savage, writing the afterword to the 2001 reprint of The Power of the Dog novel.) Like Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain, maybe The Power of the Dog is best understood as not dismantling the genre, but rather leaning into and drawing out particular aspects, in an effort to revise and expand our view of the Western.

Examination of Masculinity

Anton: All that said, I do think the film’s examinations of masculinity are a subversion of what Campion thinks previous Westerns are saying and doing. In the first half hour especially, it did seem to me that Phil was a caricature of “toxic masculinity,” but then he becomes more complex as the film reveals his hyper-masculine performance to be a self-conscious reconstruction of the persona of the rancher he idolizes, his mentor and beloved, Bronco Henry.

Aren: What an amazing name!

Anton: As a name, it really distils the Western!

So this is where I get hung up about the movie. I still can’t tell whether I think the movie’s characters, particularly Phil and Peter, remain caricatures of different types of masculinity or are purposely crafted types meant to reveal the construction of gender. How sophisticated is the film’s treatment of Phil and Peter? I’m still kind of on the fence. At times, they seem layered; other times, they seem like cartoons.

When Phil says, “I stink and I like it,” it’s farcical unless we understand it as part of his self-conscious performance of being a grubby rancher. And even then, the line and its delivery is pretty on-the-nose. At the same time, you can’t ignore the fact that Phil checks off every box of what many today label “toxic masculinity.” While I don’t think the film remains totally simplistic, I do think that attacking toxic masculinity in Westerns is part of the film’s project.

Although I agree, Anders, that you could remake this film along classical Hollywood formal lines and norms, which makes sense given that the source material appeared in 1967. After all, how many Westerns and old movies (I’m thinking of King Kong) have guys straight out saying, “I don’t like women”?

In my view, Peter is also portrayed as a caricature at times. When we first meet him, he plays like a stereotype of an effeminate boy. Speaking with a soft-spoken lisp. Making paper flowers. Holding a close and guarded affection for his precious mother. The film checks all those boxes.

Which is why I can’t make up my mind whether the caricatured portraits of these two characters, Phil and Peter, are flat cut outs to which details and dimensions are gradually added. I don’t deny that there are layers to the characters, but I’m left unsatisfied by the film’s continued fixation on caricatured aspects, as well as the opposition it sets up between Phil and Peter as two types of masculinity. You could say that the film deconstructs that opposition, showing the intense and initially hidden connections between Phil and Peter, but then how do we read the ending? That Peter is just even more ruthless, and better at surviving?

And then The Power of the Dog is just so Freudian, which is perhaps why I don’t like aspects of the movie. Does sexuality undergird all human relations? Does repression necessarily manifest itself in antagonism to the desire or behaviour being repressed? Of course, all this Freudian stuff is pretty prevalent throughout film history.

Anders: OK, that helps to clarify your reservations. I felt it was clear that with Phil at least, there are layers of self-deception and self-conscious exaggeration in his character. Is it the film that is obsessed with the way that these archetypes (even if they are more cinematic than historical) shape our self-conception, beyond even just sexuality.

I’m just not convinced that the film’s reflexive examination of a man who’s hyper-masculinity is a self-conscious performance makes it “subversive” (I don’t like the term “toxic masculinity” and the way it gets bandied about as shorthand in the culture wars, but rather I’m more interested in exploring how aspects of masculinity can be damaging when taken to excess).

Anton: But I don’t think you can just toss off the idea that the film is about toxic masculinity, even if you don’t like the quick and easy takes on the film or that concept. I think that that conception of masculinity is central to what Campion does here, particularly in selecting and adapting her source material. Why adapt this novel in this cultural moment? You might think a lot of the criticism out there is reductive, but I also think the film and its story and its characterizations can be reductive at times, even if I think, overall, it largely succeeds and escapes a totalized simplification. In other words, in my view, the film’s success can be measured by how simple and bad it could have been, telling essentially the same story.

Anders: I would push back against that simplicity because while I think Phil’s sexuality is clearly a part of his self-performance and perhaps the reason it got traction in this cultural moment, I don’t view it as the sole underlying interest. I don’t think you can say “If Phil was just less awful in his masculinity and could openly embrace his sexual desires it would all be fine.”

In fact, this is a film as much about loneliness, alienation, and how a rough environment can breed particular behaviours. If anything, the film almost presents the homosocial environment as pushing Phil into desire for men, even if he may have had tendencies in that direction. Like, saying “I stink and I like it” and rejecting heterosexual familial structures is as much about his hatred of Yale and his parents as it is anything else. He’s angry that his brother, George (Jesse Plemons), is reproducing that particular structure that he has worked so hard to avoid.

Compare it to one of the paradigmatic characters in the genre: Ethan Edwards in John Ford’s The Searchers (1956). Isn’t that film similarly aware of Ethan’s revulsion and hatred of the Comanche and how it sours his familial relations and ability to be a part of society, even if similar themes are present, if less explicit, in so many other Westerns?

As for the behavioural motivations, I guess I’m more of a Freudian than you. I won’t deny that the movie does make a central claim for sexuality to some degree, but I also think it’s pretty clear that Phil’s obsession with Bronco Henry extends beyond any sexual relationship they may have had, even if Phil’s desires play a part in his rejection of domestic life. Bronco Henry is a symbol for him, a symbol of his rejection of Yale and his family and all the propriety, which Rose (Kirstin Dunst) and Peter threaten by domesticating his brother, George. In this sense, his “queerness” is as much in his rejection of familial bonds and the “freedom” that both the gay man and the cowboy share. But it’s worth thinking about how those narrative devices actually shape the character.

It’s also worth talking more about Peter because he’s kind of an inversion of the old trope of the homosexual predator, as in the idea of older males taking a young gay man under their wing. It is Peter instead who insinuates Phil’s desire and constantly makes the next move, asking him to be more explicit (“Were you naked?”), steering Phil into a trap. He uses Phil’s inclinations to destroy him.

Anton: OK, but think about Phil’s response to his brother’s marriage and his overhearing the newlyweds having sex that first night. Phil goes into the barn and polishes and caresses Bronco’s saddle. Is it possible that Phil could be obsessed with Bronco without it being ultimately sexual? I’m not saying our interpretations of Phil should attempt to de-sexualize his relationship with Bronco; I’m pointing out that the film suggests that sex and power underly all human relations, which I don’t really I agree with.

Anders: OK, so it undermines the logic of the narrative for you since you don’t buy that as a primal motivation. I guess I do buy it as a fairly primal motivation, even if it doesn’t underlie all relations. Given the history of the family, their treatment of Phil, his failure to integrate into his social class, et cetera, I think it makes eminent sense that these various things would become linked in Phil’s psychology to Bronco Henry, who represents everything in opposition to them. So, while I would still argue that Phil’s obsession with Bronco precedes any sexual experience with him, it also exceeds it, no? But I do think it necessary to have the homoerotic reading. Without it, you’d lose the whole Peter subplot and the way in which Phil’s desire to have the power to be free of family and reject domestication actually leads him into a different trap.

There are various kinds of affinity and attraction, friendship and romantic love, but often they are entangled and difficult to separate because they have an affective power, as in they move us unconsciously and we express them in the ways we are trained and socialized to do so. The Power of the Dog explores how slippery the lines between our feeling of desire and its expressions can be. I think the fact we’re having this discussion is proof the movie is more than many of its fans—or detractors—think.

Aren: Exactly! It’s a film that deserves interrogation and examination.

Anton: But what is the film saying about the Western, as a genre, as a whole, with this particular characterization of Phil? I think it’s criticisms are more subversive and far-reaching than either of you have been suggesting.

Aren: I think there’s something essentially true in Anton’s comments, which is that if the film is great because it’s a deconstruction, and it’s a deconstruction of “toxic masculinity,” then how is it great if no one believes in the thing it’s deconstructing? There is no critic or average viewer who will watch this film and approve of the way Phil acts (well, almost no one). They might admire his vigour or aspects of his character, but no one is going to argue he’s not a lout and a villain to the others on screen. So if that is what the film is deconstructing, it’s a failure, since there’s no longer a meaningful icon to throw down. Deconstructing toxic masculinity is lazy, since it’s such an easy target. The culture has already shifted, so it’s a pat observation.

That being said, I think this is a problem in the interpretation of the film, not the film itself. In the film, I don’t think Phil is meant to be an avatar of “toxic masculinity” and nothing more, even if he resembles a lot of the qualities that people talk about when they have their socio-political arguments about masculinity.

Basically, I think Phil’s obsession with Bronco Henry cannot be boiled down simply to repression, but that’s definitely a key way he expresses himself. But the way that Peter exploits that repression is what made the film really work for me. It’s not just a matter of, “Phil is secretly gay and that explains everything.” It’s that he is so beholden to an image of what he thinks he should be, he has created a major blind spot in his worldview that can be exploited. He is worshipping an idol that he has created in his mind and he bends his will to shape himself into the image of that idol. He literally worships at an altar to Bronco Henry in the barn. And since Bronco Henry is dead, Phil is free to let his imagination run wild about his conceptions of the man, and turn him into something approaching a god. So Phil’s greatest sin in the film is not that he is a brutish woman-hating man or that he’s nasty to others or that he rejects civilization, it’s that he worships a false god and he has destroyed his humanity in the process.

But so many critics can only read this film as arguing that “old cowboys were entirely toxic and this film shows how bad they are,” which I think is so reductive of the movie and how it explores its characters. Especially if you examine the other men in addition to Phil and how they all portray other aspects of masculinity.

Anders: I would add that many readings of the film are too centred on Phil ultimately, and don’t account for George or Rose or Peter and how they play into things, which introduces a broader exploration of domesticity, class, and socialization in a hostile environment. Rose and Peter threaten the fantasy that Phil has created for himself by reinstating the familial structure that Phil found stifling and is rejecting, to build on Aren’s brilliant reading.

Aren: Yeah, exactly. To be fair, Cumberbatch’s performance is so massive that it does kind of overshadow everything.

Anton: His performance does take over the movie. Early on in the movie, I was wondering if he was miscast, but as it goes on, Cumberbatch really delivers, even if his performance is overwrought at times.

Anders: He’s gotta be up there for Best Actor alongside Oscar Isaac in The Card Counter and Adam Driver in Annette for me. I think The Power of the Dog is on the whole a broader story of loneliness, family dynamics, et cetera. I also think that the comparison to Brokeback Mountain only works in so far as we understand Phil’s connection to Bronco Henry as perhaps the only genuinely meaningful relationship in his life, one that I think precedes and exceeds any sexual feeling as I said before.

Aren: The fact that Phil is this Ivy League genius who rejects culture complicates things and makes it clear that he’s performing for the other characters in the film—and himself. The movie really does have a Billy Budd dynamic going in how it explores repression in a character and also digs into some elemental aspects about power and desire.

Anders: Totally.

Anton: And if you think of Walt Whitman, there’s definitely some connections in the American imagination between rejection of civilization, ruggedness, the natural world, and homosexuality. So what’s good about this film is it’s tapping into a lot of different things, in all the different reference points.

Aren: It’s also worth noting that there has also often been a lot of erotic energy in the Western genre anyway, even if it’s genuinely subtle in old movies. You weren’t going to get a scene where a character indulges his sexual interests in a John Wayne film like you do here, but that doesn’t mean such a scene would’ve been out of place. So it’s interesting to have The Power of the Dog put these aspects more front-and-centre that usually go unspoken in older entertainment. It does seem like a very considered examination. I’m curious how much is in the novel which I haven’t read and was written in the 1960s, when revisionism and subversion were key interests of American art.

Anders: The fact that it’s based on an old novel definitely feels right.

The Meaning of the Title

Anton: One last question for you both is, what do you make of the title? What is “the power of the dog” in the film?

Anders: Yeah. Obviously on the surface it’s the reference to the Psalm that is quoted in the film.

Anton: Psalm 22:20: “Deliver my soul from the sword; my darling from the power of the dog.” In the context of the film, Peter reads out the verse from the Book of Common Prayer after Phil’s funeral. I like how the word “darling” recalls so much Western dialogue.

Anders: Yes, My Darling Clementine (1946), the old John Ford film with Henry Fond as Wyatt Earp. It’s interesting that the “darling” from the King James version is rendered “my life” or “my precious life” in many other translations. So, it connects the precious or darling to one’s own soul or existence.

Aren: I dug into the use of Psalm 22 in my blurb for the Arts & Faith Ecumenical Jury for 2021. Basically, the meaning is dual purposed: to Peter, Phil is channelled by the power of the dog and he’s what must be defended against; to Phil, the power of the dog is something to wield for himself, that animating principle that gives him power over others.

Anton: In Psalm 22, the speaker is one isolated from the community. That’s why Jesus quotes the psalm on the cross: “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”

But I’m curious whether we also read the power of the dog as human group dynamics—I’m thinking of notions of alphas, betas, et cetera. Is the film critiquing that kind of a vision of humanity, as power struggle and hierarchy within a group? Or is the film suggesting that brute power relations undergird everything?

Anders: The isolation fits thematically.

Anton: Well, Peter reads the lines. I think Peter is the psalmist. And Phil is the dog.

Phil is also the one that sees the dog pattern in the hillside; and only Peter later is able to see what he sees. So there’s also a Freudian idea of hidden reaches of the self bound up with the dog motif and their both seeing the pattern in the hillside.

Furthermore, is the dog an emblem of a certain vision of the world that Phil holds: dog eat dog?

Anders: Because Peter also sees Phil as the threat to the family. It seems to suggest that Phil threatens the possibility of happiness for Rose and George.

Anton: Yes. Phil represents an animal power dynamic on some level. He’s all about survival and who exerts dominance. But maybe both view the other as the dog. The one disrupting the community. Phil has that line where he says, “The boy needs to become human,” which for him means to be smart about survival and dominance. And that’s partly what their relationship becomes: Phil teaching Peter how to survive, how to be tough, and how to become human.

Aren: That line reminded me of the Bene Gesserit test in Dune. (haha) When the Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohaim tells Paul, “If you had been unable to control your impulses, like an animal, we could not let you live.” It’s a funny comparison, but I think there’s more in common in both films in how they explore power than may be apparent at first glance. Regardless, there’s a lot to explore in The Power of the Dog, and while people may disagree (as we have) about how successful it is at exploring masculinity and the West, it’s undeniably one of 2021’s most provocative films.

The Power of the Dog (2021, Australia/New Zealand/United States/United Kingdom/Canada)

Directed by Jane Campion; written by Jane Campion, based on the novel by Thomas Savage; starring Benedict Cumberbatch, Kirsten Dunst, Jesse Plemons, Kodi Smit-McPhee, Thomasin McKenzie, Genevieve Lemon, Keith Carradine, Frances Conroy.

John Adams is smart about politics and history but also has a careful eye for friendship and marriage.