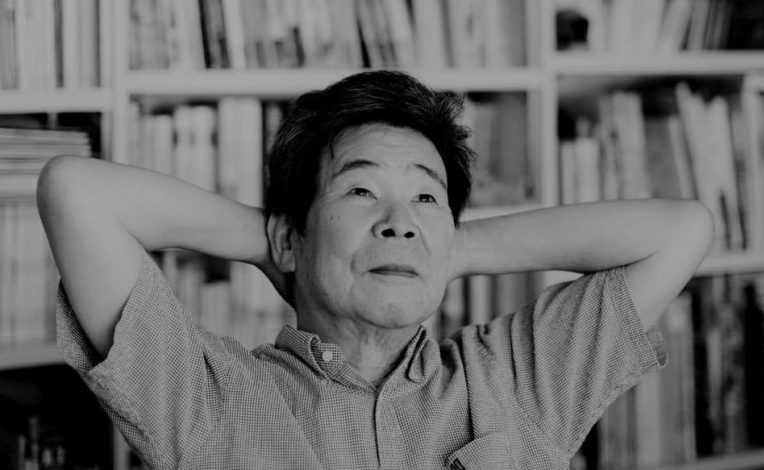

Remembering Isao Takahata

Isao Takahata co-founded Studio Ghibli along with Hayao Miyazaki and Toshio Suzuki in 1985 and for most of his career, he was defined in comparison to Miyazaki. According to conventional opinion, Miyazaki was fantastical while Takahata was adult and complex. Miyazaki translated to international audiences while Takahata’s films were too rooted in Japanese cultural specifics to break out internationally. These statements are not entirely false, but they’re reductive and make it sound like Takahata lived in the shadow of Miyazaki, which he most definitely did not.

Isao Takahata, who died April 5, 2018 from complications of lung cancer, was a master of animation and as much a titan of Japanese cinema as Miyazaki. In many ways, he was also Miyazaki’s mentor. He was older than Miyazaki and on many of their earlier pre-Ghibli work, such as Heidi, Girl of the Alps, Takahata served as director while Miyazaki was an animator. Although it’s easy to discuss Takahata in relation to Miyazaki, he deserves more than mere comparison. He was an artist in his own right and one of the most significant animators of the 20th century.

Takahata’s film have their share of whimsy, but there’s also an emotional weight to his characters that isn’t present in many animated films. His animation style is more inspired from Japanese woodcuts and watercolours than manga. He uses negative space to create frames within frames and visually capture the feeling of memory or myth. The deliberate style and emotional complexity of his films can be off-putting on first viewing, especially if you’re a child when you first watch his films, but each new viewing brings with it a greater appreciation of his work and an unpacking of the many layers hidden within them.

The first Isao Takahata film I ever saw was Grave of the Fireflies, his heartbreaking depiction of two children struggling to survive in war-torn Tokyo at the tail end of World War II. I was already a Studio Ghibli fanatic at this point, but I hadn’t ventured beyond the work of Miyazaki. Grave of the Fireflies opened my eyes to the possibilities of animation. Although the film follows two children, it’s a mature and emotionally-wrenching film that is hardly meant for kids. What’s most immediately striking about Grave of the Fireflies is the unflinching depiction of the atrocities of war. The main characters, Seita and Setsuko, die by film’s end and Takahata doesn’t shy away from showing first-hand the hellfire of war.

However, the film is not simply a work of punishment. It also contains moments of beauty, whether it’s a nighttime vision of fireflies or revelry in the sweetness of gumdrops. It’s also a fascinating look at the stubbornness and individuality of childhood. After their mother dies, Seita and Setsuko go to live with their aunt, but Seita decides to leave as he hates his aunt’s abusive nature. This willful refusal of dominance ultimately leads to Seita and Setsuko’s death. It’s understandable and natural for Seita to refuse the emotional abuse his aunt inflicts on him and his sister, but by acquiescing to pride, he sows the seeds for his and his sister’s death. Grave of the Fireflies is a wise enough film to show that pride is both beautiful and potentially destructive.

While I was immediately struck by how moving Grave of the Fireflies is, I was more lukewarm on Takahata’s other films as I watched them. I found Pom Poko off-putting in its mixture of environmental fable and cartoonish humour. My Neighbors the Yamadas proved too culturally-specific for me; as a 16-year-old, I couldn’t connect to its simple vignettes of ordinary Japanese life. I haven’t revisited either of these films in several years, but I’m sure I’d now appreciate them as I’ve grown more accustomed to Japanese culture and less focused on the immediate entertainment value of a work as its primary virtue. As well, as I’ve continued to explore Takahata’s works as I’ve grown older, I’ve found a uniform artistry in each film I watch. This makes it more than obvious to me that Pom Poko and My Neighbors the Yamadas are not bad films; it’s simply that I was too much a child when I first saw them.

In more recent years, I’ve caught up with Takahata’s early pre-Ghibli features and have come to further appreciate all that Takahata brought to animation. His debut feature, Horus, Prince of the Sun, offers a prototype for the sort of boisterous adventure that would become Studio Ghibli’s hallmark, especially in films like Castle in the Sky. Although the film’s animation now seems rudimentary, the energetic movement of the characters and the blending of myth and adventure tropes with psychological realism set in motion the wave of influential anime in the seventies and eighties.

His later feature, Gauche the Cellist, further shows how adept Takahata is at wielding simplicity in his framing and storytelling. The story follows a struggling cellist in a small town who learns to master his music each night as he’s visited by animals from the forest. The film follows a simple structure and has a gentle conceit that allows for anthropomorphized animals to interact with Gauche and impart accidental wisdom. The focus on classical western music, especially Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony, demonstrates how Takahata was deeply influenced by parts of western culture, even if his films remain fixed within a Japanese context.

Horus, Prince of the Sun and Gauche the Cellist broadened my view of what Takahata could accomplish as a filmmaker. However, none of his films (save Grave of the Fireflies) have been as impactful as Only Yesterday and his final film, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. Only Yesterday is one of the great explorations of memory and nostalgia. It follows a Tokyo salarywoman, Taeko, who takes a summer vacation to a working farm. During her time on the farm, she reflects on her past self and we see memories of her childhood in the sixties play out on the screen.

Only Yesterday profoundly explores the ways that childhood can extend into adulthood and how the passions and failures of youth can radically impact the adult years of a person’s life. Moments in the film feature some of the most painful, unadulterated vignettes of childhood ever put on screen, whether it’s Taeko’s father forbidding her from pursuing acting or her refusal to go out for dinner with her family in a quiet, desperate bid for attention and affection. Few films are so able to tap into the unique experiences of childhood—even childhood as a girl, as we see in several scenes revolving around the girls at school getting their periods. That a quiet, male filmmaker like Takahata could so profoundly tap into the psyche of a 12-year-old girl is a testament to his skill as an artist and storyteller (and shows how severely limited the imaginations of mosts artists are in our modern culture).

However, the film would not be as great as it is if it were merely a depiction of childhood. It’s the frame narrative of a disaffected young adult reflecting on her past that gives the film its nostalgic bite and powers its brilliant depiction the past. Takahata has Taeko’s childhood essentially haunt her, with childhood characters sometimes interacting with her adult self and memories overpowering the narrative thrust of Taeko’s present day. Takahata’s animation leans into the ethereal nature of the past scenes. He animates them as if in a haze, with backgrounds without outlines and white space invading the edges of the frame. Takahata was never content to simply depict something; he always strived to use the cinematic form to convey a message beyond realism.

His final film, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, is his most radical innovation. The entire work is done in a striped-down, brushstroke style that recalls the woodcuts of medieval Japan. The film is based on one of the oldest written Japanese stories and depicts the life of a magical girl who is found by simple peasants within a bamboo stalk and who grows up to be a beautiful princess. While the mythic narrative allows Takahata to depict magical occurrences and draw on centuries of tradition, the film is not a departure from Takahata’s thematic obsessions with individuality and childhood. The central tension is Kaguya’s desire to be a normal girl, while her magical heritage and the pressures of the world force her to become a princess and little more than a passive object of admiration.

I’ve written about the film’s most striking scene before, where Kaguya flees a banquet at her palace and races back to the woods where she grew up, with the animation stripping down to thick, monochromatic brushstrokes that capture the raw emotions that Kaguya feels. The scene is essentially a distillation of what Takahata was so good at as an animator and storyteller: it captures the struggle to chart one’s own course in the world and determine one’s destiny; it uses deceptively-simple animation techniques to innovate stylistically; it embodies the furious energy and visual grace that can only be captured in hand-drawn filmmaking.

At the 2013 Toronto International Film Festival, I saw the premiere of The Tale of the Princess Kaguya and was lucky enough to listen to an in-person Q&A with Takahata where he reflected on the likelihood of it being his final film. He mentioned that he would love to continue working on more films, but he knew he was a slow worker and that he probably wouldn’t last the 10 years he needed to produce another feature film. He said it with a plain-spoken wistfulness, one of an old man at peace with where he was in life but still hungry to do more.

I would have loved to see what Takahata would conjure next, but there’s a poignancy to The Tale of the Princess Kaguya being his final work. It’s a thematic capstone to his career and a beautiful demonstration of what made him so special as a filmmaker.

Takahata was a filmmaker of wisdom and artistry, a man who made movies that capture the endless struggle to define ourselves as individuals and make peace with the chaos around us. His style of artistry paved the way for so many other animators to follow, but it can never be replicated. Thus, with his passing comes the passing of a unique voice and style of animation.

Rest in peace, Isao Takahata (1935-2018).