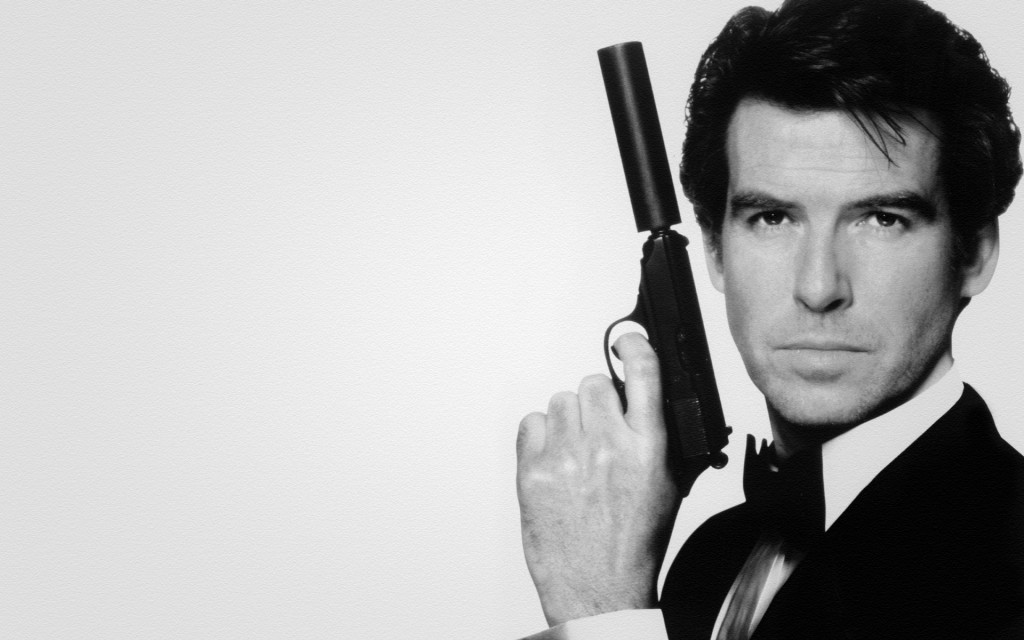

Roundtable: James Bond 007: Pierce Brosnan

The Bond we grew up with.

Aren: We grew up with Pierce Brosnan. He was the first Bond I was ever aware of and for a good portion of my life, he defined the role for me. GoldenEye was my introduction to the series and it’s largely responsible for my investment in Bond as a character. If you had asked 12-year-old me who his favourite James Bond was, he wouldn’t have hesitated in naming Pierce Brosnan.

Anton: Yup, I remember our parents renting GoldenEye on VHS. That’s really my first encounter with Bond that I can remember. Of course, I also played the later video game endlessly. Tomorrow Never Dies escaped my radar when it came out (perhaps I was too busy in line for the Star Wars Special Editions as a late grade schooler), but The World Is Not Enough was the first Bond film I saw in theatres. I saw Die Another Day in theatre as well, and actually mostly enjoyed it at the time.

This was before the James Bond Ultimate Collection on DVD, which really helped me to delve into the Bond canon. Before that, I saw Bond films in high school on a one-off basis, or absorbed a few during the 007 weeks on cable TV. I remember my cousin and I became pretty big fans of Connery as teenagers, but even then Brosnan was probably my second favourite after Connery. For a kid growing up in the nineties, Brosnan wasn’t a Bond to be discovered, he just was Bond. To his credit, even though he’s no longer one of my favourites, he did the job well.

Anders: That’s exactly it. He just “was” Bond at that time. It’s a credit to his performance that to someone untutored in the older films, he seemed to be perfect. And in a lot of ways he was. It was only later, in high school when I started to explore the older films in the series, that I became a Connery die-hard. In the mid-nineties, Connery for me was Indiana Jones’s father. Pierce Brosnan was James Bond. I think the first film I saw Brosnan in was Mrs. Doubtfire, where he plays the rival to Robin Williams for Sally Field’s affection. But even there, his combination of good looks, smarmy charm, and British affectation seemed perfectly suited to what I knew of James Bond at the time. As I said in my review of GoldenEye, Brosnan radiates charm. He’s affable and happy to play the role of Bond as best as he can, swilling martinis and wearing tuxedos.

Brosnan’s debut, GoldenEye, as it was for you each, was also the film that got me into Bond. It was the first one that I saw—I think I saw it in theatres with my 13-year-old friends, but regardless it was a big part of our imaginative life at the time and we watched it on video a bunch—and it really registered as a major film event for me despite my not having any history with the series previously. I even remember the Shreddies cereal box with the movie tie-in cover, and how it stoked my anticipation to see the film itself. Subsequently, I saw every Bond film in the theatres as soon as possible. So, their marketing in retrospect was successful in bringing the character to a new generation, and establishing Bond as something that a young movie fan should be into. And Brosnan was the right guy to embody Bond as they did it. Brosnan, whether we think he was best or worst, effectively became the face of Bond.

Aren: He did. Even now, I think he’s a good Bond. I feel like I need to reiterate again that there have been no bad portrayals of Bond in the entire franchise—only good ones. But looking back at his films without the glaze of nostalgia, he’s hardly the best.

Anton: Exactly. If we were to rank the actors who play Bond, it wouldn’t be about saying which are good and which are bad. To the producers’ lasting credit, they found an icon in Connery, and subsequently were very savvy about protecting the property by choosing actors wisely. Even the most questionable choice in retrospect, George Lazenby, who turned out not to payoff in the long run, made sense at the time, and it could have worked out better than it did. Of course, Pierce Brosnan had been on Albert Broccoli’s mind throughout the 1980s, and he’s one of those actors who, if he didn’t become Bond, would always have been considered someone who could have been Bond.

Roger Moore 2.0.

Aren: In certain ways, Pierce Brosnan is the most referential of the Bond actors, aside from George Lazenby. Similar to how Lazenby went to Sean Connery’s hair-dresser and suit maker in order to impress Harry Saltzman and land the role of Bond, Brosnan is a deliberate callback to Roger Moore and the seductive Bond of the 1970s. His hair is perfectly coiffed. He’s an undeniably attractive man who women love, but he’s also less dangerous than Connery or Dalton or Craig. There’s nothing rugged about Brosnan. He’s sophisticated. He’s the gentleman spy, not the bruiser Connery or the vulnerable Craig or the conflicted Dalton. He’s smooth and he’s confident and you don’t doubt that he’s intelligent, but you somethings wonder if he’s outmatched physically in a room, much the same way you do about Roger Moore in his later films.

Anders: Yes, Brosnan plays Bond as a sophisticate. His Bond is a man of taste and refinement in many aspects of his life, contrasting with his brutal job. In an early draft screenplay of GoldenEye, Bond foils a terrorist plot on a train in the opening sequence by noting the sommelier make a mistake in serving the wine and suspects him for a disguised agent. I can’t help but feel that the casting of Brosnan was to play that kind of Bond, even if the films called upon him to do much more.

Anton: So they were going to rework the sequence from From Russia with Love, where Connery’s Bond spots Ned Grant as a double agent because he orders the wrong kind of wine? I agree that Brosnan comes across as more sophisticated, but we can’t forget that Connery’s Bond is still a connoisseur.

Anders: Despite all the various ways that the films themselves attempt to negotiate bringing Bond into the post-Cold War era, Brosnan’s portrayal plays up the wish-fulfillment aspects of the character. In his first present-day introduction in GoldenEye, he’s seen driving a fancy car and seducing his female field evaluator. Brosnan’s Bond lives a life of luxury and indulgence when he’s not called upon to save the world.

Aren: I think all of this is very deliberate on Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson’s part. In the mid-nineties, the Dalton films were seen as a financial letdown, as well as an unwanted venture into serious territory. Licence to Kill only made $34 million at the domestic box office. When GoldenEye was released 6 years later, it made $106 million. People weren’t thrilled with Dalton’s less-humourous take on Bond. GoldenEye may continue some of the serious thematics of Licence to Kill, but Brosnan’s way of playing the character diverges from Dalton. He’s more in the line of Roger Moore, bedding every woman in the room, allowing his charm to get out of tense situations instead of savagely beating up everyone in the room.

I think this notion of retreading ground, of going back to the type of Bond that the masses loved in the 1970s and early 1980s contributes to my changing attitude towards Brosnan. I used to prefer him as the suave, sophisticated Bond, but I’ve really warmed to Roger Moore, and now, when looking back at Brosnan as Bond, I ultimately prefer Moore.

Anders: Yes, I probably do now too. Brosnan’s Bond has a glib charm, as I’ve noted. Roger Moore may have been unflappable, but he wasn’t glib. Brosnan’s Bond has a hard edge to him as well, and is comfortable with dealing out a serious body count. Perhaps the main reason to prefer Moore is that the films of his era, for the most part, seemed to know what to do with him. Brosnan is not as well served by his scripts. He’s asked to do everything and more, and each of the Bond films that he made goes off in different directions as well: from the more grounded, personal GoldenEye, through the tech-action-thriller of Tomorrow Never Dies, through the goofy, gaudy Die Another Day. He has to be cool, but funny; badass (surfing!) and classic. He acquits himself just fine, but I’m not really sure he ever got the film he deserved after he settled into the role. GoldenEye is still his best film, despite his still developing in the role as Bond (his Irish brogue faded over the course of the four films). But that has as much to do with the script and his co-stars as anything.

Aren: You’re right. And I don’t want to overemphasize the comparison between Brosnan and Moore. I think it was as much a marketing tool on the producers’ part as it was an essential aspect of Brosnan’s performance. He’s not trying to copy Roger Moore, but he is playing the character very similarly, which lends itself to natural comparison.

Kill count.

Anton: At the same time that Brosnan is more of ladies’ man, a sophisticated charmer, he also racks up the highest kill counts among the different portrayals. His weapon of choice is a machine gun really, and he also probably uses the most military vehicles, including tanks, helicopters, jet planes, and hovercraft.

Brosnan is pretty good at playing the action hero, and he often comes across as more of a soldier than a spy.

Anders: Yes, Brosnan’s Bond really takes the military aspect of the character to a new level. Dalton’s Bond first moved the character towards a more active engagement, but Bond as written during the Brosnan era really embraces the character’s special forces training. Perhaps this explains why GoldenEye was such a good choice to serve as the basis for the first-person shooter game. Did the rise in popularity of such video games influence the character, or vice versa?

Aren: This is one of those things that is almost shocking about Brosnan and contributed to my scoffing at James Bond as a spy when I was younger. He is so quick to shoot people with a machine gun!

Brosnan is almost never interested in going undercover. In the few occasions that he does, like in Tomorrow Never Dies when he goes to Elliot Carver’s party or in The World Is Not Enough where he pretends to be the Russian nuclear scientist, he only keeps up the facade momentarily. In the case of The World Is Not Enough, the dropping of his cover is immediately followed up by a machine gun fight. Brosnan is a quick trigger finger and he kills dozens of people over the course of his four films. He’s much more likely to shoot the bad guy than to try to trick him. Maybe this conflicts with our notion of him as the charmer and seducer—a less dangerous Bond—but in fact, I think it’s him making up for his physical deficiency when compared to Connery or Dalton. Brosnan uses the gadgets and weapons to do the job for him. You’re not going to find him duking it out like Connery’s Bond with Red Grant on the Orient Express or smashing up a bathroom like Craig in the opening of Casino Royale.

Here’s a handy infographic on the kill counts in all the Bond films, and, as you can easily see, Brosnan tops the charts with 135 kills.

Anton: Does Brosnan also get beat up the most, after Craig, who is actually tortured? As I said in my review, the lethal edge that Brosnan works in the opening sequence of The World Is Not Enough is probably him at his most dangerous.

The sensitive action hero of the nineties.

Anders: And yet, despite Brosnan’s skill with a machine gun and glib charm, he really does try to bring some nuance to the character. Successfully, or not, the series under Brosnan’s tenure continued to develop and investigate the character’s psyche. You have moments of this in the earlier films, with On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and Licence to Kill, but Brosnan’s series consistently explored Bond’s personal link to the story. Whether it was an allusion to an existing connection to one of the other characters, as with GoldenEye’s Trevelyan and Tomorrow Never Dies’ Paris, or just a fleshing out of the character’s motivations to greater or lesser success, it seems that in the Brosnan era, Bond couldn’t just be a cartoon, but had to have at least some grounded, realistic element to him. Beyond all the quips and martinis, Brosnan’s Bond gestures towards being a real human being with a real psychology. When the film itself becomes a cartoon, as in Die Another Day, this isn’t always going to work so well, but it definitely marks a progression that would lead to the full embrace of Bond’s characterization in the Craig films.

Anton: I think the combination of Brosnan’s emphasis on style and charm as well as all-out military-style combat suggests that his Bond is another step towards showing how “James Bond” is very much a shell, a form of armour protecting the person beneath. Connery and Moore inhabit their roles entirely, and we get a strong sense that they love what they do. They became secret agents because of who they were perhaps. Dalton often acts like a guy playing Bond; he plays up the theatricality and performativity of being a secret agent. Brosnan’s performances expose a rawness and humanity beneath Bond, but they also play up the main ways Bond survives in his dangerous line of work: his roles as a seducer and as a killer. In this way, Brosnan’s Bond almost becomes the man he is because of the work he does.

Looking back, you can also see how Brosnan fits into the nineties (especially early nineties) interest in more sensitive action heroes after the machismo of the eighties action heroes. The popularity of Kevin Costner probably helped fuel this trend, but I think it’s also about having action heroes who don’t have to be antagonistic towards women.

You can see the filmmakers grappling with this cultural development in GoldenEye, when they don’t want to change the character, but cannot overlook how Bond’s previous approaches to women are no longer considered appropriate. Remember, it’s at this time that workplace sexual harassment becomes something people discuss and call out. They even awkwardly have Moneypenny say something about that in one of the films.

Aren: I think their engagement with sexual harassment is one of the reasons I’m a little indifferent to Samantha Bond’s Moneypenny and her relationship to Brosnan’s Bond. She’s constantly calling out Bond for his chauvinism, but aggressively pining for him when he’s out of the room or actively pursuing other women when on assignment. Moneypenny has always had an inappropriate office relationship with Bond, but at least Lois Maxwell didn’t seem weak in her knees for Bond to the extent that her verbal dueling with him just seemed a false front. She flirts with him because she gets fun out of it, never really expecting Bond to go her way. Even when she’s crying at Bond’s wedding in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, you can interpret her sadness as being as much about her happiness at Bond finally growing up and becoming a real man in her eyes as it is about missing her chance to land Bond herself. Maxwell’s Moneypenny never buys into Bond’s excuses and seems to truly understand him, instead of merely pining for him.

The way they handle this relationship in the Brosnan films could be interpreted as Moneypenny only calling out Bond’s casual sexual harassment because it’s not directed at her. It’s a little uncomfortable.

Anton: We’ve already mentioned Judi Dench’s M, and how she calls Bond out for his misogyny.

Anders: Yes, with Brosnan there is a touch of self-awareness, both in the scripts and in Brosnan’s performance. Dench’s comments are meant to show that the series itself is aware of the chauvinism and sexism in the series, but Brosnan’s performance in that scene in GoldenEye always struck me as though he is slightly wounded by M’s comments because they strike so close to home. He covers it with his feigned indifference, but he’s hurt by her appraisal. I think this is where we can sense that touch of Roger Moore again, in the way that Brosnan plays the character as aware of himself. Not to the level where he’s breaking the fourth wall, but in that his Bond knows what his character is to an extent. He’s neither the “blunt instrument” of Daniel Craig’s portrayal, nor the hard, cool agent of Sean Connery’s.

Anton: Lastly, in terms of representations of masculinity, I just want to point out how beauty standards even for men have drastically changed in the past decade and a half. This might sound silly to point out, but I think it’s interesting in Die Another Day that Brosnan’s more sensitive Bond still has a hairy chest. Connery’s legendary hairy chest is something of joke nowadays, but it seems that in 2002 Brosnan can be a hairy (not ungroomed) man and still project sex appeal on the big screen. Nowadays, the standard is for men to have hairless So-Cal chests in Hollywood movies, not to mention the fact that every actor in an action/superhero movie gets insanely ripped. Of course, of course, beards are in, etc., but what I’m talking about is the standard on screen in most mainstream American movies today, particularly when the actor takes his shirt off. Craig’s rising from the water in 2006 is not only a significant moment in terms of the type of gaze it’s assuming—a female gaze—in contrast to Honey Ryder coming up for the male viewer’s enjoyment, and its repetition in Halle Berry’s Jinx. The moment also represents a new standard for masculinity, both in terms of body hair and muscle. Craig is the first Bond to be absolutely ripped. The others, apart from Moore, usually look quite in shape, but the standard changes hugely over the decades.

Maybe all this suggests as well an increase in female viewership, or an appeal to female viewership, on the part of the producers beginning with Brosnan and continuing through the Craig years. Or does it start with Dalton?

Aren: I think it undeniably shows the increasing interest in courting female viewers, much of which has to be a result of Barbara Broccoli. Brosnan was essential in actualizing the producers’ desire for a four-quadrant Bond film. He appeals to women, he appeals to men, he appeals to children. He’s safe, but he’s dangerous. He was the perfect Bond for the nineties.