James Bond 007: Diamonds Are Forever (1971)

Diamonds Are Forever is the biggest miscalculation in the James Bond 007 series, although not its worst film. It marks the end of Sean Connery’s tenure as James Bond: he goes out in easily his weakest entry, even if his performance in it is an improvement over his lackluster work in You Only Live Twice. It’s also the series’ entrance to the 1970s, that gaudiest of decades, but it doesn’t know what to do with Bond in a decade where he seems like a relic. It’s the follow up to On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, ostensibly using Bond’s rage at Tracy’s death as fuel for his vendetta against Ernst Stavro Blofeld, but it never mentions Tracy’s name and ignores the emotional fallout of the previous film. Most notably, it’s a unrecognizable adaption of an intriguing Ian Fleming novel as well as a sad attempt to recreate the magic of Goldfinger. As a result, Diamonds Are Forever is both entertaining and boring, a narrative misstep with some notable sequences, and a demonstration of why Bond needed to take a different direction in the 1970s with a different actor at the helm.

Much of the failure of Diamonds Are Forever has to be viewed in relation to On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, as the producers did not want to repeat that unique film’s perceived mistakes. After OHMSS, the sole George Lazenby entry in the series, underperformed at the box office—it only made half of You Only Live Twice’s gross—and Lazenby left the role of James Bond, Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman hustled to find a replacement to Lazenby and return the franchise to its blockbuster-gold status. After considering many actors for the role (including John Gavin and Michael Gambon), United Artists pressured Broccoli and Saltzman to get Sean Connery to return to the role that made him an icon and them a fortune. They succeeded in that regard by offering Connery the enormous salary of $1.25 million, a record at the time, and by having United Artists agree to back two of Connery’s pet projects.

With Connery once again in the starring role, Broccoli and Saltzman enlisted Tom Mankiewicz and Richard Maibaum to write an adventure plotline that’d draw on the Las Vegas setting of Ian Fleming’s novel, Diamonds Are Forever, but also replicate the success of Goldfinger. It appears that they did not want another emotionally complex, formally experimental Bond film that sidelined globetrotting adventure in favour of character introspection and focused action. The result is a tonal oddity, one that is jarring as a follow-up to OHMSS.

Diamonds Are Forever ignores the ending of OHMSS to such an extent that only retconning the entire previous film would have gone further to avoid its implications. Its opening plays off the audience’s expectations of dealing with the fallout of OHMSS, but it never explicitly acknowledges the previous film’s events. It has Bond out for revenge against Blofeld, but Tracy Bond’s death is never mentioned. Ernst Stavro Blofeld is again the villain, but he’s played by Charles Gray instead of Telly Savalas and his exploits at Piz Gloria are never discussed. Bond is not a broken man. He is merely an agent filled with rage at Blofeld, taking out a vendetta against a foe that constantly eludes him.

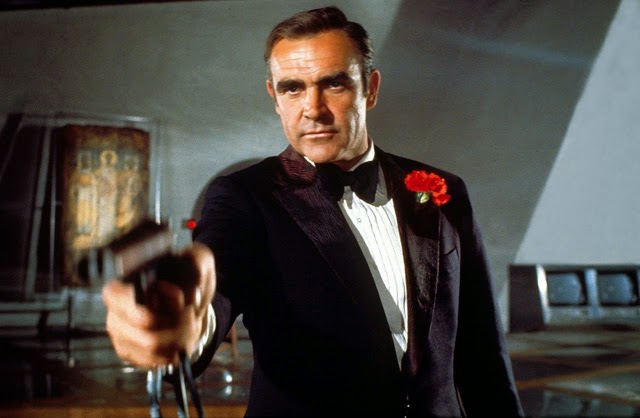

In other ways you can view the beginning of Diamonds Are Forever as the direct continuation of You Only Live Twice, skipping over the events of OHMSS altogether. Certainly we can read Bond’s ambiguous anger at Blofeld as as much a result of Blofeld’s escape at the end of You Only Live Twice as it is an outcome of OHMSS’s events. In the effective teaser, we see James Bond searching for Blofeld, beating his way through various lackies to get information on the criminal mastermind’s whereabouts. But already we can tell that this is a different Bond that the one that came before: neither the cold, impersonal killer of Dr. No nor the emotional athlete of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. At first Bond is kept in the shadows, similar to how Lazenby’s identity is masked in the opening of OHMSS. But once we get a look at Bond when he says his famous line, we realize it’s Connery and that he looks older. His puffy hair is a noticeable toupée. He’s a bit wider in the stomach and chest, but it’s not muscle filling him out. He still relishes the quips and the insults—one hilarious moment has a gangster say “Hit me” at a Blackjack table, only to have Bond spin him around and sock him in the face. But, there’s none of the youthful lustre and tiger-like energy of Connery in his prime. James Bond was no longer a young man—and the franchise had yet to return him to his youthful roots, even if they could have by adapting Fleming’s Casino Royale.

Diamonds Are Forever is a film adrift, wanting to tap into former glory while being stranded in a time and place where its central hero looks as quaint as Sherlock Holmes. The 1970s and James Bond were an odd fit throughout all five films that occurred that decade—the relaxed sexual mores of the 1970s removed Bond’s ladykiller allure, leaving him as a white, conservative defender of the Old Empire—but only in Diamonds Are Forever does the crew behind Bond seem so perplexed as to what to do with the character.

As they saw it, their only option was to look backward, to recapture past glory while upping the camp factor, mistaking the silliness and outlandishness of the Bond films as their primary appeal. If Diamonds Are Forever was intended to avoid aspects of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, it was certainly intended to copy aspects of Goldfinger. Broccoli and Saltzman hired Guy Hamilton to direct, got Richard Maibaum to contribute to the screenplay, and had Connery again in the lead role. The action is again centred in America. There’s a flamboyant villain who’s meant to be a debonair mirror of Bond himself. Shirley Bassey again sings the theme song—easily the best thing about the film and the best theme song the series ever produced. The title even references another precious commodity that the plot revolves around.

The film is structured similarly as well. We start with a pre-credit teaser where Bond wraps up a previous mission in stunning fashion, before moving onto the main plot, which once again requires M (Bernard Lee) to sit James Bond down with a government expert—a conversation that includes an effectively satirical montage of the diamond industry. M even reiterates his confoundment at Bond’s snobbery, when Bond guesses the base year that the sherry he’s offered is made from. Bond then inserts himself into a criminal operation, posing as an interested smuggler, turns a criminal vixen (Jill St. John’s Tiffany Case instead of Honor Blackman’s Pussy Galore) into an ally, and eventually defeats the villain’s master plan even while remaining his captive. Clearly director Guy Hamilton and the producers were having fun by going through the paces that made Goldfinger so successful. However, where Goldfinger cleverly subverts Bond’s privilege and vices, Diamonds Are Forever celebrates them as a preferable alternative to the more-serious character ruminating on love-versus-duty presented in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

The deliberate mirroring of Goldfinger goes so far as the producers even considering making the film’s villain the twin brother of Auric Goldfinger, eager to mete out revenge on James Bond for killing his brother. This would have worked just fine, as the Blofeld we get in Diamonds Are Forever resembles Gert Fröbe more than the conniving, charismatic nemesis played by Telly Savalas. Unfortunately, none of Goldfinger’s thematic richness carries over to Diamonds Are Forever’s attempts at imitation. Charles Gray’s Blofeld is certainly cosmopolitan, with his long cigarette holder and fancy penthouse at the top of the Whyte House, but he doesn’t resemble Bond or reveal any greater depth about our main hero. His vices are not his undoing as Goldfinger’s were, as he descends into camp villain territory, inspiring countless parodies with his flurrid diction and silly devices like a diamond-encrusted death satellite and dinky bathosub.

Diamonds Are Forever’s attempts to replicate Goldfinger are less than successful, and distract away from the potential of a more straightforward adaptation of Ian Fleming’s novel. I don’t put too much stock in judging the Bond films by how they adapt the novels they’re based on, but it’s perplexing that the producers and writers would jettison so much of the novel’s gangster focus in favour of shoehorning in SPECTRE and Blofeld. The Spangled Mob villains are a natural fit to Las Vegas in a way that Blofeld isn’t, especially after the events of OHMSS. As for the Howard Hughes-inspired plotline involving Willard Whyte (Jimmy Dean), the notion is an intriguing enough concept to support its own narrative, but as an addendum to the Blofeld focus, it merely complicates an already convoluted plotline.

The best parts of Diamonds Are Forever are the ones that hew close to the novel. Bond’s assumption of the identity of diamond smuggler Peter Franks (Joe Robinson) provides the film with many action and comedy highlights. The fight scene between Robinson and Connery in the cramped European elevator of Tiffany Case’s apartment continues the series’ longstanding tradition of chaotic fight scenes. The close quarters amplify the impact of each punch. The camera doesn’t have much room to move, but the framing of the elevator cage alone does much to achieve claustrophobia and heightened adrenaline. Fights like this also show Connery’s renewed energy in the role. Diamonds Are Forever may be his worst film, but Connery is having a blast, relishing the quips and muscular acting that he thought were a drag only a few years earlier. The fact that he used his enormous salary to establish the Scottish International Education Trust probably contributed to his positivity towards the performance. Too bad the film doesn’t have better things for him to do, although it does provide him with hilariously silly moments, like hiding in the shadows with his arms around himself, pretending to be a couple making out, as well as his atrocious attempt at a Dutch accent that crescendos with “Who is your floor?”

The other borrowed aspect from the novel that works surprisingly well is Bruce Glover and Putter Smith as Mr. Wint and Mr. Kidd, homosexual assassins that Blofeld employs to procure the diamonds for his satellite and dismantle the smuggling ring. Mr. Wint and Mr. Kidd are psychotic and absurdly-suppressed villains, finishing each other’s sentences and slowly traipsing around like deranged clowns. But they achieve a strange balance between sinister and humourous. Their endless aphorisms—”If God had wanted man to fly—” ”—He would have given him wings, Mr. Kidd.”—are hilarious, but their calm omnipresence unnerves the viewer, and catches Bond off balance. They’re the only villains in the entire film who resemble any serious threat to Bond, best exemplified by their locking him in a casket and sending him off to be cremated in the funeral parlour furnace—the tensest moment in the entire film. They beat Bond and if it weren’t for the greediness of rival gangsters, Bond would have died at their hand.

As for what they add to the film’s thematic interests, I’m not sure. I’m not actually sure the film has many thematic interests, as it’s more interested in spectacle and fun than subtext. There’s a lot of posturing about identity and whether Bond is really any different from the criminals he disguises himself among, but none of it lasts into the climactic gunfight. For the most part, the film is a muddled attempt at bringing Bond into the 1970s. Its style and location and design all speak to the decade’s influence—is there any more 1970s city in the world than Las Vegas?—but Connery’s Bond doesn’t fit in with the world he inhabits here, nor does the franchise make his dissimilarity to the cultural landscape the character’s defining characteristic, as they did with Roger Moore in his films.

Diamonds Are Forever is certainly enjoyable, but if any film in the franchise necessitated a rethinking of how to approach the character and the world he inhabits, this is it.

5 out of 10

Diamonds Are Forever (1971, UK)

Directed by Guy Hamilton; written by Richard Maibaum and Tom Mankiewicz, based on the novel by Ian Fleming; starring Sean Connery, Jill St. John, Charles Gray, Jimmy Dean, Bruce Glover, Putter Smith, Norman Burton, Joseph Furst, Lana Wood, Bruce Cabot, Lois Maxwell, Desmond Llewelyn, Joe Robinson, and Bernard Lee.